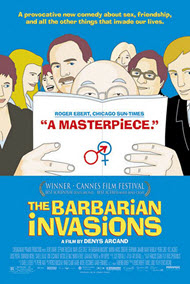

The Barbarian Invasions

for language, sexual dialogue and drug content.

for language, sexual dialogue and drug content.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Foreign Crime Comedy Drama Sequel |

| Length: | 1 hr. 52 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2003 |

| USA Release: |

March 5, 2004 |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Rmy Girard, Stphane Rousseau, Dorothe Berryman, Louise Portal, Marie-Josee Croze |

| Director |

|

Denys Arcand |

| Producer |

| Daniel Louis, Denise Robert |

| Distributor |

Here’s what the distributor says about their film: “Remy, divorced and in his early fifties, is hospitalized. His ex-wife, Louise, asks their son Sebastien to come home from London where he now lives. Sebastien hesitates; he and his father haven’t had much to say to one another for years now. He relents, however, and flies to Montreal to help his mother and support his father. As soon as he arrives, Sibastien moves heaven and Earth, brings his contacts into play and disrupts the system in every way possible to ease the ordeal that awaits Rimy. He also reunites the merry band that marked Rimy’s past around his father’s bedside: relatives, friends and former mistresses. What have they become in this age of “barbarian invasions”? Are the old irreverence, friendship and truculence still there? Do humor, hedonism and desire still inhabit their dreams? In the age of the barbarian invasions, the decline of the American empire continues…” (presented in French with English subtitles)

This is the sequel to the Oscar-nominated Canadian arthouse film “Decline of the American Empire” (1986).

“The Barbarian Invasions” is a French Canadian movie that won this year’s Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. It opens with a long tracking shot (reminiscent of Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil” and Francois Truffaut’s “Day for Night”) which follows a nurse and a visitor down a long crowded hospital corridor. The camera passes patient after patient, each one relegated to a space in the hallway because no hospital rooms are available. The patients are ignored for the most part while doctors and nurses flip through charts or talk on the telephone. The visitor finally finds his father who is lucky to be have a bed which is actually inside a room. There are two other patients who share the room; one has brought his own television; the other is emptying his own bedpan.

In this brief, understated intro we get a glimpse of government sponsored and government controlled universal health care. It is not the utopia promised by academic theorists or political bureaucrats. It is a nightmare that makes the post office, child services, and even welfare look positively efficient by comparison.

I don’t believe that the filmmaker intended to condemn Canada’s health care system. He merely uses it as a backdrop to support, condone and even encourage a more sinister and troublesome evil. He creates a scenario in which assisted suicide and euthanasia are considered justifiable, and even courageous.

If you think logical arguments will be presented from both sides of the euthanasia debate, you are mistaken. The “right to die” argument is framed in gold leaf with enough sentimentality to make the viewers of the Lifetime channel blush. No one talks about the right to live. We see this same scenario played out in our courts and in our press today. A current case in Florida is a real-life example of what is at play in “The Barbarian Invasions.” Over and over again we listen to arguments about whether a person should be allowed to die. How often does one of those judges or reporters talk about whether that person should be allowed to live?

Sebastien, a successful international business man, lives in London. He comes to Montreal to visit his father, Remy, who is dying of terminal cancer. We aren’t told what the cancer is, but the determination of its extent and its prognosis depend on the results of a PET scan. The waiting time for one of those in Canada is six months so Sebastien arranges for his father to travel to Vermont to have the test and for the test to be interpreted by a specialist in Baltimore. The father’s health care, comfort, and even the drugs used for his “mercy killing” all depend on the son’s wealth.

The hospital is exposed as a hotbed of union and administrative corruption as the son keeps doling out more and more under the table fees for special favors. Without Sebastien’s wallet that constantly runneth over, father and son would be at the mercy of the same forces as are the patients we saw earlier, sick and abandoned in a hospital hallway.

Remy is a retired history professor, a liberal academic who indulged in sensual adventures-his many mistresses come to visit him during his final days; his wife proving herself to be a remarkable trooper who sits nonjudgmentally on the sidelines of this parade-as well as intellectual pursuits. He admits to falling for all the fads of academe: socialism, communism, deconstructionism (“There was never an “ism” that we didn’t fall in love with,” says one of the mistresses, with a nostalgic smile.). Remy acknowledges the less than utopic outcomes of those “isms”: the 6 million dead in the Ukraine, the 20 million dead from Mao’s “Great Leap Forward,” the 2 million dead in Cambodia’s Killing Fields, etc. He feels more betrayed than duped by his heroes’ mass murders. He equates intellectual victimization with real bloodshed. No wonder Lenin referred to his ilk as a group of “useful idiots.”

Remy goes pretty easy on Mao and Stalin compared to the vitriol he unleashes on Pope Pius XII (big surprise: an academic who dislikes a pope) who, according to Remy, allowed the Holocaust to happen. I don’t blame the filmmakers for trotting out that old war horse (so many of them do), but they reach Noam Chomsky levels of absurdity when they imply that the September 11th barbarities are somehow on a par with the many “barbarous deeds” committed by American imperialist invaders over the last two centuries. In Remy’s world all things are relative, even the most immoral of acts.

With the help of a corrupt policeman and a junkie with a heart of gold (she’s the daughter of one of Remy’s mistresses) Remy finds sufficient doses of heroin for his father’s pain control and eventual suicide. According to the film, heroin is a lot more effective than morphine, or anything else, in treating pain. Again, no alternate point of view is presented. The people who provide and administer the poison are presented as self-sacrificing heroes. The nurse who administers the fatal dose carries the syringe in her mouth before she injects the poison. I guess sterile technique can be discarded when the patient is being discarded too.

The euthanasia setting is romantic in a wistful, “moon river” kind of way: fading sunlight, a lakeside cottage, a campfire, wine, marijuana, hugs all around. But there are some cracks in this twilight kingdom by the lake. The son finds himself turning into the same kind of man his father was, the kind of man the son often resented. Sebastien has already attained authority over his dominions. With his wealth he can almost turn stones into bread. In his own small way he is like the rulers that his father was once so enamored of.

Those tyrants worshiped and believed in a power that handed kingdoms over to them. Those kingdoms lasted for awhile, but only for awhile. Their legacies are landscapes covered with graveyards and rivers filled with blood. I don’t mean to say that the son is a mass murderer on par with Stalin or Mao, but his lack of respect for his father’s life is a microcosm for a lack of respect for all life. I would have admired him if he had helped his father bear his cross. Instead, he used his money and influence to coax his father off the cross.

“The Barbarian Invasions” has a veneer of warmth, respectability and sophistication, but at its core sits a cold heart. It is a movie about death disguising itself as a celebration of life. Taking a human life, especially a vulnerable one, is nothing to celebrate.