Memoirs of a Geisha

for mature subject matter and some sexual content.

for mature subject matter and some sexual content.

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Biography Historical Romance Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 25 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2005 |

| USA Release: |

December 9, 2005 (NY/LA/SF) December 16, 2005 (limited) December 23, 2005 (wide release) |

Japanese culture

Loss of parents

About ORPHANS in the Bible

Child abuse / child slavery

Japan in the 1920s to 40s

War and an occupied nation

Coming of age

Forced prostitution

About prostitution in the Bible

Student mentor relationship

Jealousy

Betrayal

| Featuring |

|---|

| Ziyi Zhang, Ken Watanabe, Gong Li, Michelle Yeoh, Yoki Kudo |

| Director |

|

Rob Marshall |

| Producer |

|

Columbia Pictures Dreamworks Pictures See all » |

| Distributor |

“A motion picture based on the novel by Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha”

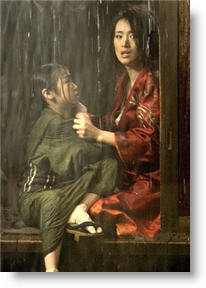

Plot: In the 1920s, 9-year-old orphan Chiyo (Ziyi Zhang) gets sold to a geisha house. There, she is forced into servitude, receiving nothing in return until the house’s ruling hierarchy determines if she is of high enough quality to service the clientele—men who visit and pay for conversation, dance and song. After rigorous years of training, Chiyo becomes Sayuri, a geisha of incredible beauty and influence. Life is good for Sayuri, but World War II is about to disrupt the peace. Although she has become the most famous and sought after geisha in her district, she cannot be with the Chairman (Ken Watanabe), the man she really loves.

“Memoirs of a Geisha” is a lushly shot, skillfully acted, and competently directed film. The soundtrack, while overbearing at times, utilizes the skills of Itzhak Perlman on the violin and Yo-Yo Ma on the cello. It will no doubt garner praise for its technical artistry and sympathetic portrayal of gender oppression. My own response was more reserved.

I guess the key moment in “Memoirs of a Geisha”, from a Christian perspective, comes when the orphan Sayuri receives a kindness and a monetary gift from a then stranger on a bridge. To this point in her life, Sayuri has been trying to either escape the house in which she has been sold or merely survive as a slave. She takes the money she has received, more than she has ever had in her life, to the temple and sacrifices it as an offering to accompany her prayer. She wants to be a Geisha so that she can possibly see this man again and be a part of his world.

We are not reminded of this prayer until the very end of the film, two hours (and it is a long two hours) later, when we are told—and we must be told, because we don’t necessarily see it—that everything in her entire life has been an answer to this prayer and that everything she has done, every step she has been taken, has been to bring her closer to this man. Oh, we understand well enough that she longs for a life of her own. We understand, too, that having been born into a life with no education, money, or prospects, the only way of having anything is to accept one in which nothing is really hers. The way to hurt a man who has nothing, Stephen R. Donaldson once wrote, is to give him something broken. Apparently that tactic works with women as well, so yes, we feel the generic sympathy for Sayuri (and those like her) who are themselves sacrifices to the unattainable and often unarticulated dreams of others.

If I could pause for a moment, though, not to fully deconstruct the film’s messages—choice is better than no choice? love is better than prostitution?—but only to point out how very, very ambivalently they are embraced by the film itself, I might be able to account for the curious lack of emotional power with which the film passes over you. “Memoirs of a Geisha” is one quickly moving, impersonal scene after another: our sisters are sold into slavery scarcely before the credits are over, Sayuri moves from attendant servant to debutante geisha in a few training sequences (was I the only one who kept hearing “Team America”’s “Montage” song in my mind?), World War II is covered with a quick shot of some flying planes and a symbolic shot of red silk floating in a river, Sayuri regains her status before we even realize she has lost it.

In other words, things just sort of happen in “Memoirs”. Some of them are interesting, some touching, but like Sayuri’s dance, they are more surface than substance. In the rush to cover so much material, director Rob Marshall rarely gives us enough time to invest in any of the characters; as a result, the things that happen to Sayuri seem more like a series of movie obstacles than true personal tragedies. It is a dramatic movie with an action movie sensibility—beautifully shot, it’s never more than five minutes away from a dramatic plateau or payoff. The tension never rises, though, and the narrator’s voice-overs becomes prosaically expository rather than poetic.

The key to the emotional pull of a romance is the audience’s desire to see the principals together. Choices they make that keep them apart, even misguided ones, extract pathos only if we understand that they should be together. We understand that Sayuri wants the Chairman, but we know nothing of whether he wants (or only desires) her until the end of the film. We aren’t really sure whether she wants him—him you understand, not the illusion of him, nor the memory of a kindness, nor simply the abstract freedom of choice that is symbolized in him, but him—until the credits roll, and we deduce (more than know) that this is a happy ending.

One problem with the material that the film never solves is that the geisha are apparently supposed to be implacable. The masks they wear to make themselves inaccessible and mysterious make it difficult for the audience to connect with Sayuri and believe the depth of her feeling. The novel doesn’t have this problem; it is told in flashback, and the confessional mode of the narrator allows you to be drawn into her inner, emotional world in a way that the film’s chronological structure and observational point-of-view do not.

Finally… okay… I’ll say it. For all the film’s insistence that geisha are not courtesans nor prostitutes, for all the underlining that Sayuri’s prayers and choices are the product of the absence of choice, the film ultimately celebrates the institution of geishahood for providing an escape from poverty and never seriously gives much thought to the price that it extracts. When Sayuri’s virginity is auctioned to the highest bidder, we are invited to linger over her triumph in extracting the highest price in history while the cost of the earnings is only hinted at as she lies down to a discreet fadeout. Love, we are told, has led Sayuri to pray to be able to give herself to the highest bidder. Equal love has led the Chairman to remove himself from that bidding. And the greatest love answers her prayer, not seeing that it isn’t really the true prayer of a soul that knows herself and has a name for the unfamiliar longings that have been born inside her but rather the confused and desperate prayer of a child who has been given kindness as a pusher might give drugs to a junkie and who finds herself willing to sell everything to have another sample.

My Grade: C+

Violence: Mild / Profanity: Minor / Sex/Nudity: Mild

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

If you are a creative or artistic person, you’ll definitely enjoy the shear beauty of this film. The sets, lighting, costuming, and camera work are all spectacular and capture the exquisite world of the geisha in a very vivid way that makes this film a joy to watch, even if you don’t appreciate the story. I have not read the book, so I don’t know how closely the movie follows it, but from an entertainment standpoint I feel this movie is worth seeing.

Average / 3½

All in all, and excellent movie for teens and adults, and mature children, as long as you note the warnings.

Average / 5

Average / 4

Westernesque kissing itself was not a form of affection known to the Japanese and so those scenes betrayed the authenticity of any attempt by the producers to convey true culture to viewers. Such contact of the lips and tongue was considered disgusting by the majority of Japanese as late as the mid 20th century. Conveying both culture and a story takes good audio effects. But the foreign accents of many of the actors were so severe that it was very hard to follow the plot for anyone not familiar with Asian languages. Perfect English dubbed in would have been preferred, along with a smattering of pure Japanese placed in greetings and other short encounters.

Finally Miss Ziyi Zhang did a great job considering her nationality and the paucity of cultural knowledge of her American directors. She also conveyed how the universal value of virtue needs to prevail in any culture. Just wish I could be a fly on the wall in a Japanese theatre to see the reactions on the faces of native Japanese as they viewed this attempt by Americans, sans good native advisers, to recreate an important historic institution.

Average / 3

Offensive / 4

Extra plusses to this movie: an amazing soundtrack, featuring YoYo Ma and Itzhak Rabin (Ma’s cello, as I’ve seen in extras, symbolizes Sayuri, while Rabin’s violin symbolizes the Chairman). Also, the introduction of Suzuka Ohgo, who plays young Chiyo—the girl gave a wonderful performance, and her talent and just plain cuteness will hopefully ensure we’ll see more of her.

Average / 5

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Average / 5

Offensive / 2

Better than Average / 3

Better than Average / 4

The one thing that irked me about the movie (and many may consider this to be splitting hairs) is that the actors were Chinese rather than Japanese. Narrow-minded individuals may argue that “it doesn’t matter,” but for the movie to seem as if it took place in a certain area and culture, it would have been wise to have Japanese actors. The musical features and use of scenery and visuals is stunning, and I highly recommend this film for teens to adults.

Average / 5

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

The cinematography is beautiful and the actors are very appealing. Director Rob Marshall did a fantastic job of making the movie look like a lavish fairy-tale in this Cinderella-esque story of a young girl sold into slavery to an “okiya” (geisha house) and her overcoming obstacles of poverty, abuse, and dispair to become the most celebrated geisha of her time.

Ultimately, the story is one of love and sacrifice, which resonates with me as a Christian (and a hopeless romantic!) Though the movie is rated PG-13 (the book is definitely an R, in my opinion), some Christians may feel there are too many suggested sexual situations and one assault scene that might be disturbing (though no full or partial nudity is shown, it is strongly implied).

The heroine, Sayuri, is a generally good character, though she is not a Christian, because she comes from a traditionally Japanese background. She works hard; is, for the most part, obedient to her elders/mentor; and was even sympathetic to her tormenting rival at the end. Her driving force is to be part of the world of the man she has fallen for, which leads her to make a rash and morally-questionable decision at the end that is shocking, but is integral to the bittersweet nature of the final outcome.

Overall, I would recommend this movie for its lavish beauty, memorable characters (especially the dynamic between the three geishas: Sayuri, Mameha and Hatsumomo) and pining romance. For those who have read the book (and loved it), I would just caution you not to raise your expectations on how well the nuances are captured in the movie. For me, it is enough to have a beautifully-made film that for the most part kept to the original theme of the book to do it justice.

My Ratings: Better than Average / 5