Hellhouse

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Teens Adults |

| Genre: | Christian Documentary |

| Length: | 1 hr. 26 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2002 |

| USA Release: |

March 10, 2002 |

Is there an actual place called “Hell”? Answer

Why was Hell made? Answer

Is there anyone in Hell today? Answer

Will there literally be a burning fire in Hell? Answer

What should you be willing to do to stay out of Hell? Answer

How can a God of love send anybody to Hell? Answer

What if I don’t believe in Hell? Answer

The Good News—How to be saved from Hell. Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Aria Adloo Ashley Adloo Amy Allred Gabriel Allred Cherie Asbjornson Tim Ferguson Jim Hennesy Jennifer Hillman Howard Holt Kaleb Holt Kayce Holt See all » |

| Director |

|

George Ratliff |

| Producer |

|

Zachary Mortensen Selina Lewis-Davidson George Ratliff GreenHouse Pictures Mixed Greens Media Cantina Pictures |

| Distributor |

| Seventh Art Releasing |

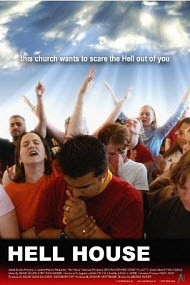

“This church wants to scare the Hell out of you.”

The subject of George Ratliff’s complex and weirdly ambivalent documentary, “Hell House”, is the Halloween program at the Pentecostal Trinity Church in Cedar Hill, Texas. The “Hell House” program stages a series of skits which terminate in a purgatorial ante-room that gives each of the more than 75,000 guests who annually see the program a choice: go to heaven or, the implication is, go to hell.

The “rooms” of “Hell House” depict dramatic recreations of teen suicide, date rape, drunk driving, and drug dealing, as well as the hot-button issues of abortion and AIDS. In the film’s most startling scene, a dying girl is wheeled into a hospital emergency room wearing a white t-shirt, white sweatpants, with her knees raised, legs spread, and “bleeding” heavily. The “Hell House” narration, as told by the “devils” themselves, informs the audience that she used RU-486 after having been raped.

Such, in brief, is the background and controversial essence of Ratliff’s documentary which has won nearly unanimous critical approval. Yet, perhaps too much critical emphasis has been placed on the content of the “Hell House” program and not enough on the people who stage it. What makes the film compelling is not its acting, nor its graphic depictions of disturbing social problems, but rather its behind-the-scenes look at the personal lives of the actors. Made up of young people, the cast is multi-racial and not stereotypically “church kids.” Ultimately, the film surprises as the viewer realizes it is the people and not the play that is the thing.

Ratliff films the production meetings, set construction, and interviews with the cast members, but it is the auditions that provide much of the humor, some of it unintentional, as when the “drama queens” exclaim to one another that they want to be the “abortion girl” or the “suicide girl.” The juxtaposition of Christian children auditioning for such parts is jarring and irresistibly amusing. Then, when they transform from child-like innocence into a performance of realistic anguish, the effect is irresistibly empathetic. Ratliff’s piecemeal dissection of the staging creates low expectations which he then upends by showing that the real drama exists outside the production. What should be silly or bathetic he makes funny or moving because of the dissonance he creates between the off-screen content and the on-screen form.

Howard Hawks once said that if a movie has three good scenes it will be a success, and this film has at least three. In one interview, the actor portraying a young girl raped by her father relates how she watched the crowd file into the room and was stunned to see the young man who had raped her two years before. She tells how in that moment she finally came to terms with what had happened, forgave him, and then gave her best performance. That is one of those Howard Hawks moments and is a validation of the church’s uplifting effect on young lives scarred by real world traumas.

But as successful as he is in ferreting out dramatic background material, I think Ratliff’s genius in this film stems from his use of a “cold” camera, of a camera that refuses to feel. This says as much about us as a viewing audience as it does about his technique. We are so culturally conditioned to being told how to feel by the subjectivity of the lens that we are disturbed at the absence of cues. All the secular reviews have commented on his objectivity and, writing as a Christian, I agree. It is difficult for any but the most ideological spectator to find in the film a spiritual or moral center to rest in complete critical comfort. For many Christians, the film is compromised by the presentation of the gospel as bad art; for many non-Christians, the actors are redeemed by an authenticity which defies stereotyping. Ratliff repels Christians with the melodramatic fiction of the play even as he impresses secular viewers with the sincerity of the players.

Lastly, the “choice” at the end of the tour will strike many as heavy-handed from both faith and entertainment perspectives. I thought so myself until I considered that the appropriate comparison is not between “Hell House” qua entertainment and Harry Potter, but between “Hell House” and the Freddy or Jason films. “Hell House” is not meant to be a visual analog to a “Kum ba yah” moment, but a depiction of spiritual horrors. Even so, committing oneself to Jesus is a rational decision and should not be made under duress. New Christians “count the costs,” recognize their personal failures, and acknowledge God’s redeeming love. This in turn should elicit another rational response in which the new Christian leaves the life of sin and turns to a life marked by personal holiness and good works.

To be shocked, to be confronted with a crystal-clear choice between two life styles: the world’s and Christ’s. Simplistic as it sounds, that kind of idealism is at the heart of the Christian faith: love your neighbor, forgive your offender (even a rapist), and give what is asked of you. These are some of the humanly daunting aspects of a faith that Nietzsche sneered at for its timidity.

Ultimately, “Hell House”—whatever its merits and demerits—is a fascinating depiction of ordinary people who believe in extraordinary things. Non-Christians will leave the theater feeling superior and Christians will leave the theater relieved that it wasn’t worse. Both will leave the theater having been thoroughly captivated by a unique perspective and troubled by the vague feeling that Ratliff has slipped something by that no one caught.

This review was originally published in the Journal of Religion and Film of the Department of Philosophy and Religion University of Nebraska at Omaha. Used by permission.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.