KANGAROOS - Where do they come from? Why do they hop? Did they evolve from some other animal?

Introduction

Kangaroos are the symbol of Australia. They adorn its postage stamps, coat-of-arms, coinage, and even its major international airline. At the zoo or in their natural habitat of Australia (and New Guinea), they remain the most recognized and obvious of Australia’s fauna.

Their faces, the way they carry their young in a pouch, their phenomenal leaping power, and their deadly ‘karate kicking’ have long intrigued people.

The whole family is best known as the Macropodidae—literally the “big-footed” family. This includes not just the six largest living species commonly called “kangaroos,” but also a further 48 species found in Australia alone, and another 13 found in New Guinea—67 modern species in all.

The range of two Australian species, the agile wallaby and the red-legged pademelon, spills into New Guinea as well. The term ‘modern’ is applied because this vast empire was once much greater, with over 100 species in Australia alone.1

They varied enormously in size. The tiny, scampering musky rat-kangaroo still lives in the tropical rain-forests of northern Queensland (Australia). However, the massive, blunt-faced Procoptodon is extinct.

Three basic size ranges are recognized today. At the other end of the scale from the six large types mentioned above are the rat/rabbit-sized bettongs, potoroos and rat-kangaroos. In between are the tree kangaroos (a specialized group comprising nine species that live and move about in the trees), and those commonly called wallabies.

Kangaroo Reproduction—Why the pouch?

In the desert species, carrying the baby in the pouch is convenient for the female, who may travel many miles for fresh food and water. The youngster stands a greater chance of survival because it does not have to keep up with her and is tucked away from predators.

During prolonged drought, kangaroos stop breeding. In some species, a doe [the female] is able to delay the development of a fertilized egg inside her until an older joey dies or vacates the pouch.

This remarkable phenomenon occurs in the red kangaroo, the eastern gray kangaroo, the common wallaroo (euro), the brush-tailed bettong, and several of the larger wallabies. It has also been noted in the honey possum and some non-marsupial mammals such as bats and seals.2

Another incredible aspect is that the doe can determine the sex of her offspring. How she does this is unknown, but she tends to put off bearing males until she is older. Males move away after about two years, but females stay with their mothers longer and benefit from ongoing support.3

A doe is nearly always pregnant. From sexual maturity to death, she is rarely without three offspring—an embryo in the womb, a joey in her pouch, and a larger youngster at her heels.

The joey is born after a gestation period of about 35 days (depending on the species) and in the largest species is the size of a human thumb nail. In the smallest, it is only the size of a rice grain. Naked, blind and deaf, it must make its way unaided from the birth canal to the pouch.

All going well, the climb will take less than 10 minutes. The joey can survive only a few minutes unless it reaches the pouch and attaches to one of the four nipples. Once there, its mouth swells on the nipple so that it cannot be removed without injury. A ring of strong muscles, similar to human lips, seals off the opening to the pouch to protect the joey from bouncing out, and keeps the pouch waterproof if mother goes for a swim.4

After three months, the developed joey emerges from the pouch to make short trips in the outside world. However, it will return to the pouch to suckle and sleep until eight months old.

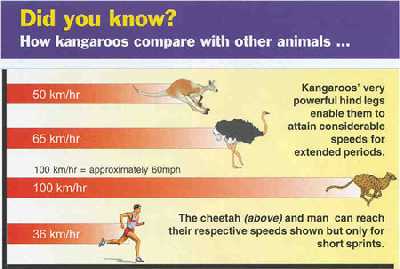

How fast are kangaroos?

Why do kangaroos hop?

Over the years, scientists have put forward theories concerning the hows and whys of kangaroo locomotion. As yet, none has fully explained every aspect.

Hopping appears to be more energy-efficient than running or galloping. The faster kangaroos hop, the less energy they use for the same distance. Treadmill studies have shown that kangaroos maintain a constant number of hops per minute. Regardless of how much the treadmill speeds up, they simply take longer and longer hops.

Kangaroos function much like bouncing balls. A ball will bounce a number of times without a fresh input of energy. Every time it hits the ground, some of the energy is shifted to the rubber, stored there, then recycled in an elastic bounce. Jumping kangaroos store 70% of their energy in their tendons, compared to running humans, who can store and reuse only about 20%.4

A hopping kangaroo also uses less energy to breathe than one standing still. Part of the secret lies in the way the abdominal organs ‘flop’ within the kangaroo’s body. Instead of using muscle power, air is pushed out of the lungs by the impact of the organs against the diaphragm at each landing.

Efficient travel is very beneficial to arid-dwellers such as the Red and Western gray kangaroos, the Tammar wallaby and the euro, which may need to travel long distances between water and feed. However, many species inhabit timbered country, with abundant food and regular rainfall.

Evolved from possums?

The Macropod family is alleged to have evolved from either the Phalangeridae (possums) or Burramyidae (pygmy-possums) during the so-called Oligocene epoch some 30 million years ago.5

However, there are no fossils of animals which appear to be intermediate between possums and kangaroos. Wabularoo naughtoni, supposed ancestor of all the macropods, was clearly a kangaroo (it greatly resembles the potoroos which dwell in Victoria’s forests).6 If modern kangaroos really did come from it, all this shows is the same as we see happening today, namely that kangaroos come from kangaroos, ‘after their kind’.

A stunning example of this is the modern rock-wallabies. When John Gould first made notes of these animals last century he mentioned only six species. Later ten species were counted, and now a total of 15 are recognized. Current research is indicating that these wallabies are still splitting into new species.7

However, such instances of one group ‘splitting’ into more groups is not evolution, as Creation magazine has pointed out repeatedly. The reason is that no new genetic information arises during such events.

Creationists have postulated that such speciation must have happened many times after the Flood, as populations of creatures separated by valleys or mountain ranges have adapted to environmental conditions within their territories. Some of the original population’s genes enable their owners to survive in their particular environments, while other genes are lost to such natural selection. However, all the genes were present in the original population. Each ‘daughter’ population carries somewhat less of this information, so is less able to respond to future environmental changes.8

They are all still rock-wallabies, and these changes did not take millions of years. In fact, seeing such ‘adaptive radiation’ happen so quickly is a great boon to creationist models. It shows how there would have been ample time since Noah’s Flood for all known kangaroo types to have come from one or a very few original kinds.9

Evolutionists explain the wide variety of kangaroos and their specialized survival methods as millions of years of trial and effort, chance mutation and selection. However, kangaroos’ superb design, their sophisticated reproductive methods and their amazing, energy-efficient locomotion did not come by any evolutionary process. For example, unless the pouch and the joey’s ability to find it were fully functional, they would have left no offspring.

Kangaroos are ingenious examples of God’s craftsmanship, designed by a Creator who knew perfectly what He was doing. To Him all praise, glory and honor is forever due.

Australia’s extinct giants

Australia once had many marsupials much larger than those remaining today. The ‘giant wombat’ Diprotodon is probably the best-known of these. The giant kangaroo Procoptodon could stand three meters (ten feet) tall. They (and also a non-marsupial, the bird Genyornis, a larger version of the emu) are collectively called Australia’s extinct ‘megafauna.’

What happened to all of these? Many have ‘devolved’ down to smaller representatives. For instance, today’s red kangaroos and Tasmanian devils are much smaller than their fossil counterparts. A recent find at Cuddie Springs in New South Wales, of human tools together with the bones of some of these megafauna, raises the suspicion that people helped drive them to extinction, which of course is no surprise for creationists. Tests have confirmed that some blood is still present on the tools, which suggests that it was probably nowhere near as long ago as evolutionists say.10

Author: Rebecca Driver. Originally published in Creation Ex Nihilo, 20 (3):28-31, June-August 1998.

How did animals get from the Ark to isolated places, such as Australia? Answer

References

Hans Mincham, Vanished Giants of Australia (Australia: Rigby Ltd., 1966). Return to text

Ronald Strahan (Australian Museum Trust), The Mammals of Australia (Australia: Reed Books, 1995). Return to text

Jan Aldenhoven, Kangaroos—Faces in the Mob (Green Cape Wildlife Films Pty Ltd, 1992). Return to text

Kathy & Tara Darling, Kangaroos on Location (New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books, 1993. Return to text

Peter Murray, Australia’s Prehistoric Animals (Australia: Methuen Books, 1984). Also Encyclopedia of the Animal World, Volume 11 (Sydney: Bay Books Pty Ltd, 1977). Return to text

Brian Mackness, Prehistoric Australia (Golden Press Pty Ltd, 1987). Return to text

The Living Australia, Issue 10 (Sydney: Bay Books Pty Ltd, 1985). Return to text

See C. Wieland, Stones and Bones, (Australia: Creation Science Foundation, 1994). Return to text

To answer the question ‘How did the kangaroo get to Australia?’ see the chapter on this topic in The Answers Book (Australia: Answers in Genesis, 1999). Return to text

New Scientist, 156 (2107) (November 8, 1997), pp. 36-40. Return to text

Text Copyright © 1998, 2002, Creation Ministries International, All Rights Reserved—except as noted on attached “Usage and Copyright” page that grants ChristianAnswers.Net users generous rights for putting this page to work in their homes, personal witnessing, churches and schools.