The Ninth Day

Reviewed by: Jim O’Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | not reviewed |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Foreign Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 38 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2005 |

| USA Release: |

April 27, 2005 (limited) |

What is the Christian perspective on war? Answer

If God is all-knowing, all-powerful, and loving, would He really create a world like this? (filled with oppression, suffering, death and cruelty) Discover the answer!

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

Does God feel our pain? Answer

What about the issue of suffering? Doesn’t this prove that there is no God and that we are on our own? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

| Ulrich Matthes, August Diehl, Germain Wagner, Bibiana Beglau, Jean-Paul Raths |

| Director |

|

Volker Schlondorff, Volker Schlndorff |

| Producer |

| Juergen Haase, Wolfgang Plehn, Jean-Claude Schlim |

| Distributor |

| Kino International Corp. |

I missed Volker Schlondorff’s “The Ninth Day” when it was released in the U.S. this summer, but I recently watched it on DVD after its December release. It is the best movie I saw last year.

“The Ninth Day” is a hard movie to watch, but I believe it is necessary to see., especially at a time when moral relativism is infecting movies the way it is infecting every aspect of our culture. When I watch forces of evil being portrayed sympathetically in “Syriana” or in “Munich” I feel outraged. I do not want to listen to a homicide bomber’s argument. On Omaha Beach in 1945, there were young German soldiers who fought in that D-day battle. They had their reasons for aiming their guns at the American GIs coming off the landing boats. Spielberg did not give us their points of view or their motivations in “Saving Private Ryan”. He took a side in that epic film. In “Munich”, he and screenwriter Tony Kuschner seem unable to take a stand. They stop short of calling evil by its name, and their craftsmanship flounders. They do not serve truth; they don’t even look for it. I am not surprised that these two films have remained largely unseen, and are now overshadowed by other films that have a moral footing and a religious core.

“The Chronicles of Narnia” is a stirring Christian parable, and “King Kong”, despite its many weaknesses, has the magnetism of great myth. Whether Peter Jackson intended the Biblical subtext is unclear, but its presence is unmistakable: the girl takes the illicit apple, the girl juggles the apple in front of the jungle prince, the girl and the prince leave the garden forever, the prince falls.

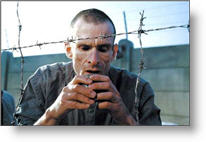

“The Ninth Day” is based on the life of Jean Bernard, a priest from Luxembourg who was imprisoned in the Dachau prison camp by the Nazis. In the movie, the priest’s name is Henri Kremer, and he is played beautifully by Ulrich Matthes. I admired Matthes’ portrayal of Josef Goebbels in “Downfall” last year. Matthes is an unusual looking actor—broad forehead, deep dark eyes, scarred cheeks—who has unusual skill. I don’t know if it’s possible for an actor to give a perfect performance, but this one comes close.

Father Kremer is given a nine day release from Dacha’s “priest block.” His release is arranged by Gestapo officer Gebhardt, played by another accomplished German actor, August Diehl. Gebhardt harbors the same doubts about man and God that Kremer faces, but the up and coming Nazi uses those doubts to construct an argument in favor of his new god and his new faith, Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. He speaks in riddles that confuse and confound, but they also appeal. What is up is down and what is down is up; betrayal and sin are as much a part of God’s plan as are grace and faith.

Gebhardt, a former seminarian, says these things with the gentility, grace and charm that only a handsome youth who is gaining the world can exude. Only when his theories are dissolved by reason or exposed by light does his well wrapped rage burst forth. Gebhardt and Kremer are, of course, two versions of the same character, less Baroque versions of the characters in Bergman’s “Persona”. Schlondorff has a different focus than Ingmar Bergman; whereas Bergman focuses on personality and psychology, Schlondorff emphasizes morality.

Gebhardt allows Kremer nine days leave in order that Kremer use his influence as a respected local priest to influence the Luxembourg diocese to conform to the Reich’s demands and to endorse its philosophy. Kremer’s refusal to do so will result in his return to Dachau. We see enough of the horrors of the concentration camp early in the film (the shrill sound of spoons scraping empty metal bowls, the palpable pain of hunger and dehydration, the humiliation of an actual crucifixion) to understand what Kremer has ahead of him if he denies Gebhardt’s requests. Kremer also knows that his own family will be at risk if he capitulates. If he acquiesces to the Gestapo’s commands, he and his family will be safe.

“The Ninth Day” is a story about a moral choice. The choice is not an easy one; nor is it melodramatic as it was in “Sophie’s Choice”.

The film is not an easy one. It does cloud moral choices or contextualize them into irrelevance the way the other films I mentioned do. “The Ninth Day” does not shy away from the politics of the period. It does not avoid the sensitive issue of Church politics. The debate over Papal policy in Germany during the Nazi years continues, and has accelerated since Pope Pius XII has been under consideration for Roman Catholic canonization. The film does not condemn the Church outright for colluding with Hitler. It gives fair treatment to both sides of the debate without detracting from the story or allowing its viewers to arrive at too easy a conclusion.

Volker Schlondorff (“The Tin Drum”, “Circle of Deceit”) is one of today ’s great filmmakers. “The Ninth Day” is the latest addition to an admirable body of work. It is a tale of quiet heroism—a “High Noon” for our time and for all times—and it is a real treasure.

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.