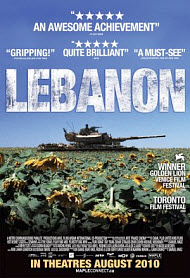

Lebanon

for disturbing bloody war violence, language including sexual references, and some nudity.

for disturbing bloody war violence, language including sexual references, and some nudity.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | War Drama Foreign |

| Length: | 1 hr. 33 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

October 1, 2009 (festival) August 13, 2010 (select) DVD: January 18, 2011 |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Reymond Amsalem (Assna), Ashraf Barhom, Oshri Cohen (Herzel), Yoav Donat (Shmulik), Guy Kapulnik, Michael Moshonov (Yigal), Zohar Shtrauss (Gamil), Dudu Tassa, Itay Tiran (Asi) |

| Director |

|

Samuel Maoz |

| Producer |

| Ariel Films (Germany), Arsam International (France), Arte France (France), Israeli Film Fund (Tel-Aviv), See all » |

| Distributor |

“Lebanon”, an Israeli film directed by Samuel Maoz, is now in limited release in the U.S. after debuting successfully at a number of international film festivals and winning the grand prize at this year’s Venice Film Festival. The short, taught, rapid-fire film is based on Maoz’s own adventures as a young soldier who fought for the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) during Israel’s war with Lebanon in 1982.

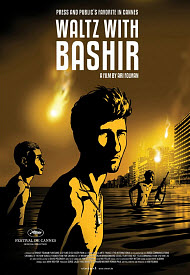

“Lebanon” has been described as an anti-war movie. I’m not so sure about that. It lacks the highmindedness of “Paths of Glory,” the mayhem of “MASH,” the despair of “The Deerhunter” and the paranoia of any of Oliver Stone’s war films. “Lebanon” has more in common with the 1981 film, “Das Boot,” last year’s “The Hurt Locker” and another Israeli film from 2008, “Waltz With Bashir.” Those works were films about war; if they were pushing a point of view, it was a subtle one. They told a war story and let the audience draw its own conclusions about the morality of war. I recommend watching “Bashir” before or after seeing “Lebanon”. Both films deal with the same 1982 Israeli-Lebanese conflict and both approach the subject and the art of filmmaking in unique, ground-breaking, and impressive ways.

All the action in “Lebanon” takes place in the small claustrophobic confines of a tank. As viewers, we are taken inside the tank after a falsely comforting opening scene of a blue sky, a golden sun and a field of lush sunflowers in full bloom. As the tank heads into battle, the iron portal shuts, and we are not released for the next ninety minutes while the armored vehicle shakes, stalls, grinds, rumbles and lurches. The interior is smoky, cramped and dirty. The sweat and soot-stained crew crouch in and wade through a foul mixture of water and oil that covers the floor. You can almost smell the cigarette butts and the food remnants that float on the surface of the goo, not to mention the dead Israeli soldier squeezed in the tank for transport to an area outside the battle zone.

The only view we, and the soldiers, have of the outside world is what we can see through the tank’s viewfinder, and even that has its glass lens shelled and cracked halfway through the film. The only outdoor sounds we hear are those loud enough to penetrate the tank’s armor. What we see through the viewfinder is limited in scope and is unaccompanied by noise or voices. Sight and sound are disconnected, and so are the senses and reality. Trying to distinguish safety from risk, passage from blockade, and friend from foe becomes almost impossible. All one can do is move forward or retreat, shoot or hold fire, destroy or be destroyed.

Inside the tank are four inexperienced soldiers, all in their twenties. Shmulik (Yoav Donat) is the untested and uncertain gunner who is unsure when to shoot and when to hold his fire. When he does shoot, he accidentally kills a fellow Israeli soldier. The mistake is tragic, but understandable in the light of the chaos and confusion that surround him. The error results from conflicting signals, lack of experience, perhaps bad instincts, and definitely bad luck. If a senseless tragedy had only one cause and one evil doer to lay the blame on, the catastrophe would be easy to figure out and easy to digest. That is the dish we are fed in the recent documentary, “The Pat Tillman Story.” Tillman’s tragedy is one that seems incapable of explanation, unless we look to Christ and to His cross for answers. Unfortunately, the documentary, that begins well enough, disintegrates into a finger pointing and finger wagging screed that stops paying attention to his subject and recklessly builds a conspiratorial political tree that lacks insight and common sense.

In “Lebanon”, it’s hard to tell who the enemy is, but it’s just as hard to figure out why a foe is actually a foe. The forces attacking the Israeli tank turn out not to be the expected Palestinian occupiers, but their Syrian allies. One of the young Israeli soldiers asks why they are fighting the Syrians and what part the Syrians play in the conflict. The young man stuck in the thick of the battle has little sense of the war’s big picture. His field of vision is no bigger than that of the tank’s viewfinder. His lack of understanding is a comment, not just on the boy’s innocence, but on war itself. Okay, I am contradicting what I said earlier about this not being an anti-war film, but if there is an anti-war message in “Lebanon,” it is one that owes more to the tradition of what I believe to be the greatest of war films, Jean Renoir’s 1937 “La Grande Illusion” which acknowledges that war is a reality, an unfortunate one that cannot be fully comprehended any more than human nature or the human soul can be fully understood.

Other characters slide in and climb out of the tank during the battle. Only during those brief moments does any light shine into the dark dank space. The IDF infantry commander, Jamil (Zohar Strauss), tells the tank crew to use phosphorous grenades on the resistance fighters. Such grenades are outlawed by an international treaty. He tells the soldiers to use them anyway; “just call them by a different name.” A Syrian (Dudu Tasa) is taken prisoner and placed inside the tank. He is handcuffed to a pole, and, although humanely treated by the Israeli soldiers, he is cruelly threatened and handled by an Israeli ally, a Lebanese Christian Phalangist (Ashraf Barhom). The Israelis form a better bond, although a tentative and silent one, with the Syrian enemy than they do with their Israeli commander or with their Phalangist ally.

Under constant threat of unexpected and immediate immolation, the soldiers struggle to survive and to connect with whatever it is they understand to be human. There are many scorching moments, but there are some poignant ones too. When the driver talks about being his family’s only son and asks his infantry commander to inform his parents that he is alive and well, we hold our breath as we begin to see how instantaneous everything can be in war, and how past and future can be turned upside down in a moment.

Earlier I mentioned Ari Folman’s 2008 animated documentary, “Waltz With Bashir,” which is a good companion film to “Lebanon.” (If you do consider viewing the film, beware that there is extreme violence, nudity, and graphic sexual content. The images are animated, but they are nonetheless graphic.) “Bashir” is about Folman’s attempt to remember what happened while he was a 19 year old infantry soldier during the same war in which “Lebanon” is set. The Israeli infantry, of which Folman was a member, provided protection and lighting (in the form of flares) for the Lebanese Phalangi forces (Jumayyil Bashir was their leader and Lebanon’s president before he was assassinated) who killed approximately 1000 Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. The animation gives the memory piece a remote, dream-like quality, but the sharply drawn lines and silhouettes shape the conflict and the atrocities with a violent and deadly clarity. Both of these films give a vivid and visceral rendering of war, and their accounts breathe in a way that only a personal testament can.

Earlier I mentioned Ari Folman’s 2008 animated documentary, “Waltz With Bashir,” which is a good companion film to “Lebanon.” (If you do consider viewing the film, beware that there is extreme violence, nudity, and graphic sexual content. The images are animated, but they are nonetheless graphic.) “Bashir” is about Folman’s attempt to remember what happened while he was a 19 year old infantry soldier during the same war in which “Lebanon” is set. The Israeli infantry, of which Folman was a member, provided protection and lighting (in the form of flares) for the Lebanese Phalangi forces (Jumayyil Bashir was their leader and Lebanon’s president before he was assassinated) who killed approximately 1000 Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps. The animation gives the memory piece a remote, dream-like quality, but the sharply drawn lines and silhouettes shape the conflict and the atrocities with a violent and deadly clarity. Both of these films give a vivid and visceral rendering of war, and their accounts breathe in a way that only a personal testament can.

Many people and many countries (the U.S. lost 241 Marines in the aftermath of the conflict when a suicide bomber attacked the Marine Naval barracks in Lebanon) suffered as a result of the conflict. The strife persists today, and as we sit at the precipice of another Israeli-Palestinian peace summit, these two films, remarkable technical and artistic achievements, can help us reflect upon the toll of an ongoing war in the Holy Land, on all wars, and on the sacrifice of each soldier in those wars.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Moderate / Sex/Nudity: Minor

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.