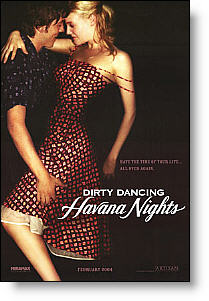

Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights

for sensuality.

for sensuality.

Reviewed by: Kenneth R. Morefield

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Teens Adults |

| Genre: | Performing-Arts Romance Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 26 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2004 |

| USA Release: |

Teens! Have questions? Find answers in our popular TeenQs section. Get answers to your questions about life, dating and much more.

Learn how to make your love the best it can be. Christian answers to questions about sex, marriage, sexual addictions, and more. Valuable resources for Christian couples, singles and pastors.

How can I deal with temptations? Answer

Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

How far is too far? What are the guidelines for dating relationships? Answer

What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Rene Lavan January Jones John Slattery Mya Romola Garai |

| Director |

|

Guy Ferland |

| Producer |

| JoAnn Jansen, Sarah Green, Lawrence Bender, Herbert Ross, Gary Lucchesi |

| Distributor |

Plot: Katey Miller (Romola Garai), finds herself in Havana, 1958, for her senior year of high school when her family moves because of her father’s job. She gradually finds herself drawn into the world of Javier Suarez (Diego Luna), a Cuban national who works as a waiter by day and dances at the local club by night. They try to keep their burgeoning interest in one another a secret long enough to win a local dance contest. Rated PG-13 for sensuality and (implied) sex.

The dancing is a metaphor for sex. We all got that the first time, right?

In 1987, “Dirty Dancing” hit the jackpot by being just risqué enough to get adolescent hearts beating, while being just PG-13 enough to convince the old fuddy-duddies that sexual smoke doesn’t always have to mean fire. It’s been seventeen years, and our culture has gotten risqué enough that getting sweaty palms over sensuous dancing, even dancing set in 1958, seems just a little behind the curve. Earlier this year, the independent film Thirteen in effect called the mother character naive in the final scene for thinking her daughter was too young to have begun to have experienced pressure to experiment with sex and drugs.

Even the original Dirty Dancing had to ratchet up the taboo factor by stretching the age limit between Jennifer Grey’s character (oh, so subtly named “Baby”) and Patrick Swayze’s dance instructor in order to add a hint of Lolita to an otherwise mundane “opposite side of the tracks” love-story. Havana Nights has no such secondary taboo, and its substitute—a backdrop of the Cuban revolution—fails to add any real sense of consequence to what we are seeing. Katey’s friends call Javier a “spic.”

Javier’s family accuse him of literally and figuratively kissing up to the Americans. Part of what makes the film’s social consciousness so lacking in drama is that it is so confused. We sense that changes are precipitated more by the plot needing something to happen than by any rational development of character. Katey’s mother (a wasted Sela Ward) slaps her for dancing with a Cuban, then expresses pride at her daughter’s dancing ability, then rediscovers her own sensuality through dance.

Javier first says he wishes to leave Cuba because of Batista, then says he will stay and fight for a free Cuba if this new guy, Castro, turns out to not be such a good idea after all. His father fought (and died) you see, for the idea of a free Cuba, so to leave it after the revolution would be to abandon his father’s dream. To have left it before the revolution would have been different because… because… well, never mind that, right now, let’s dance.

Both Luna and Garai do competent jobs with paper-thin roles. Garai, especially in early scenes, is able to convey a girl who is in search of her confidence, not just her sexuality. I actually found her character to be more interesting before she started dancing, because once she did, symbolism took over for character development. She lets her hair down, she dresses less square, and, finally, she takes a lesson from Yoda and admits that if fear is bad, doing whatever you are afraid of (like sleeping with your Cuban waiter) must be good. The sex is all silhouettes and a quick fade to black, and it is hard to tell which is the film’s bigger lie: that Katey “knows” when she leaves that she will see Javier again (I’m assuming that 44 years later she is now middle-aged and checking CNN daily for Castro’s obituary), or that in 1958 or 2008 it is possible to have have your first sexual encounter and for it to have less emotional affect on you than a really, really good mambo.

Of course, none of this would matter, if the dancing scenes delivered the goods. After all, it’s not like anyone I know watches “High Society” or “Royal Wedding” for the plot. Remember the first time you saw Michael Jackson moon-walk in the “Billie Jean” video? The dancing was electrifying precisely because you could see it. He studied Astaire and Gene Kelly and saw the importance, even in the video age, of letting the camera show the whole body so that the viewer could see the steps, the line, and the posture. “White Nights” had a laughable plot, but the giggles stopped when Hines and Baryshnokov fused ballet and tap.

Unfortunately, while we get several montages of dance snippets in Havana Nights, we only get one sustained dance sequence, and it is much more a triumph of editing than of dancing. The dance scenes here rarely show more than two or three moves or three or four seconds of full dancing before cutting to the band or the audience. The style here is closer to “Flashdance” or “Footloose” than “Chicago,” and while the film doesn’t have (or does a better job of hiding) the body-doubles that stood in for Kevin Bacon and Jennifer Beals in the former films, neither does it have Fred, Ginger, or even Catherine Zeta-Jones.

There is nothing wrong with a formula genre piece: a sports flick that ends in a big game, or a court thriller that ends with a surprise admission on the stand. If, however, you are going to make a formula film, you better bring it when you hit your set pieces. Havana Nights’ biggest failure is a failure to convince us that the king and queen of the dance floor can actually do more than three steps in a row without needing a second or third take.

My Grade: C-

[Better than Average/4½]

[Average/3½]

[Extremely Offensive/1]

[Average/3½]

[Average/2½]

My Ratings: [Better than Average/3]