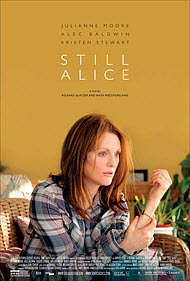

Still Alice

for mature thematic material, and brief language including a sexual reference.

for mature thematic material, and brief language including a sexual reference.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 41 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2014 |

| USA Release: |

October 13, 2014 (festival) December 5, 2014 (limited) February 13, 2015 (wide) DVD: May 12, 2015 |

effects of Alzheimer's Disease on victims and families

What kind of world would you create? Answer

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

Does God feel our pain? Answer

How did bad things come about? Answer

sadness

family relationships

ANXIETY, FEAR AND WORRY—What does the Bible say? Answer

having a father that died an alcoholic in a crash crash

feeling ashamed of memory loss

feeling loss of dignity

SUICIDE—What does the Bible say? Answer

If a Christian commits suicide, will they go to Heaven? Answer

DEPRESSION—Are there biblical examples of depression and how to deal with it? Answer

What should a Christian do if overwhelmed with depression? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Julianne Moore … Alice Howland Kate Bosworth … Anna Howland-Jones Alec Baldwin … John Howland Kristen Stewart … Lydia Howland Shane McRae … Charlie Howland-Jones Hunter Parrish … Tom Howland Seth Gilliam … Frederic Johnson Stephen Kunken … Dr. Benjamin Erin Drake … Jenny Daniel Gerroll … Eric Wellman See all » |

| Director |

|

Richard Glatzer Wash Westmoreland |

| Producer |

|

BSM Studio Big Indie Pictures See all » |

| Distributor |

Sometimes a bad film can be saved by a performance that transcends the material. Julianne Moore almost rescues Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland’s shallow and insipid “Still Alice” from its own wasteland. Moore elevates some tedious passages to moments of sparkling epiphany, but, ultimately, even Moore’s considerable gifts cannot overcome the film’s tepid writing and withdrawn direction. I have seen several TV movies, and even some TV commercials, about Alzheimer’s disease that are more emotional and more revealing than this hollow feature film.

Dr. Alice Howland (Moore) is a linguistics professor at Columbia University in New York. She is an accomplished academic, a published author, and a sought after lecturer. She is married to Dr. John Howland (a surprisingly well-tempered, and even more surprisingly lifeless Alec Baldwin) who is also a professor at Columbia. They have a happy marriage, and three grown children: a lawyer, a doctor, and a would-be actress. They live in a comfortable townhouse on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, and they spend summers at a beach-front home in the Hamptons.

Alice seems to have the perfect life, but she does have some issues: Alice’s mother and sister died in a car accident when she was young, and her father succumbed to alcoholic liver disease. Her past has taken a toll on Alice, but it has not defeated her. She is a case study of the adult-child-of-an-alcoholic who does everything to perfection. Her tight control over all aspects of her life has, until now, ensured good results and high esteem. Whether she is giving a lecture or baking a bread pudding, Alice gives it her all, and at the end of even the busiest day, she never misses her evening run. “Let go, let God,” would hardly describe Alice’s philosophy of life.

Alice is diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease when she is just 50 years old. At the peak of her career and personal life, her memory, cognitive function, and ability to recognize people start to deteriorate. The disease moves slowly at first, but it quickly escalates as it progresses toward an inevitable end. Moore sublimely conveys calm dignity, fierce determination, and sometimes naked fear even in the most mawkish of scenes. The otherwise insufferable doctor visits, complete with their tedious mental status examinations, come alive as Alice attempts to perform the memory tests that become increasingly more difficult for her.

Remnants of her sharp intellect and astute insights allow her to hold it together on the outside while seeing clearly that things are falling apart behind the mask. Moore reveals a woman who desperately tries to stay one step ahead of her disease, while understanding the reality of where that disease is taking her. Alice is too smart, and too good a planner, to delude herself, and others, but she is also a determined fighter who never lets anything, even a crippling disease, get the better of her.

But Moore can only do so much. The film rarely addresses the hard issues that Alzheimer’s disease raises: the physical as well as mental devastation, the havoc it wreaks on a patient’s family, the lack of resources available to treat the disease, and the loss of hope that often accompanies the ailment’s progression.

I recently read a new novel called We Are Not Ourselves by Matthew Thomas. It’s a long book about a family’s long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease. It is a powerful story; I could not put the book down when I was reading it, and even now, months later, I cannot stop thinking about it. Thomas takes you through a man’s decline from intelligent and honored scientist (like Alice, the main character is also a professor) to helpless invalid. Thomas spares nothing in his depiction of the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease. The reader comes face to face with what the disease is, and what it does.

Yes, novels are different than movies. They have the scope, the space, and the time to reveal much more than a movie does, but a movie can reveal something. The drawbacks of the film format can, at times, be an advantage. Julian Schnabel’s “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” used the limitations of its main character (semi-blindness and paralysis from a stroke) as well as those of the medium itself to stunning effect. Schnabel brought us face-to-face with human tragedy, but also with human redemption. “Still Alice” tip-toes toward its subject, but repeatedly backs away, especially at times when one cries out for it to look closer.

“Still Alice” tosses some moral issues around, but it never attacks them head on. The question of suicide is brought up, but it is not addressed honestly, although it does give Moore her best screen moments when a younger, mentally competent Alice addresses an older, impaired Alice by way of an earlier recorded computer message. In that video, Alice gives herself instructions about how to take her own life. The premise seems implausible (Alice is way too smart, and too concise an architect of her own life, to trust in such a flimsy plan), and it goes nowhere. Ultimately, a deus-ex-machina frees Alice, the filmmakers, and us from confronting the subject seriously.

I was also concerned about the brief side plot dealing with in vitro fertilization and genetic engineering. No one expressed ethical reservations about either practice. The filmmakers imply that, if someone can afford such modalities, they should certainly make use of them. So often in movies about diseases, especially the ones dealing with AIDS (“Philadelphia,” “Longtime Companion,” the recent TV production, “The Normal Heart”) the well-to-do are presented not as people with extraordinary advantages and opportunities, but as victims who have much more to lose than anyone else. “Still Alice,” whose executive producer is Maria Shriver, takes that same elitist page out of a dated and increasingly irrelevant “suffering in mink” playbook. In telling Alice’s story, as sorrowful as it is, in a way that protects her from the every day limitations that most of us face, her experience takes on a distance that makes it more museum piece than personal testimony, one that can be, and should be, universal.

If, during her gestation, Alice could have been genetically engineered or terminated in favor of a more “normal” baby, would her own parents have been justified in doing so? The film’s response would seem to be yes. Is a life that may develop, or does develop, Alzheimer’s disease any less valuable than a life that does not? Would we “engineer” a child, or even a mother’s makeup, using embryo selection or mitochondrial material from another mother’s eggs, to ensure a better progeny? “Still Alice” gets close to these questions but does not directly answer them.

The film does, however, act on those phenomena, as though no thought or introspection was necessary. “Still Alice” steps coyly, but also proudly, into a brave new world, one in which we hold so tightly to ourselves that we ultimately lose ourselves. Where is the notion that by coming in contact with the tassel of Someone’s cloak, “as many as touched it were healed.”

Violence: Minor / Profanity: Moderate to heavy—“G**-d*mn” (3), “Oh G*d” (5), “God” (3), “d*mn,” hell (3), f-word, s-word, “a**-hole” / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

As far as offensive items: There was some brief language, mainly in one intense scene. The issue of selective implantation of fertilized eggs was also discussed briefly in the film as a very minor sub-topic. The youngest daughter lives platonically with two male roommates, who are never seen. Alice plots a way to end her life if her memory gets too far gone. There are many scenes of alcohol consumption.

Having personally dealt with a family member with dementia, many of the scenarios rang true in this movie. It is VERY well made and gave a touching portrayal. Even though I knew what was coming, I still shed tears several times.

Julianne Moore gave a stunning and realistic performance. I disagree with the main reviewer about the way the film played out. It was based on a book and kept very true to the points. Digging into some areas and leaving some subjects to the imagination. I highly recommend this film for teens or above.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5