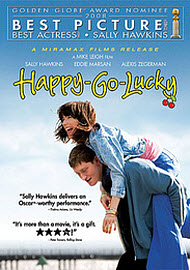

Happy-Go-Lucky

for language.

for language.

Reviewed by: Kenneth R. Morefield

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Comedy |

| Length: | 1 hr. 58 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2008 |

| USA Release: |

October 10, 2008 DVD: March 10, 2009 |

How do I know what is right from wrong? Answer

What advice do you have for new and growing Christians? Answer

Biblical women with admirable character, include: Mrs. Noah, Mary (mother of Jesus), Esther, Deborah, and Milcah, daugher of Zelophehad.

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Sally Hawkins Eddie Marsan Elliot Cowan, Alexis Zegerman, Andrea Riseborough, Sinead Matthews, Kate O'Flynn, Sarah Niles, Joseph Kloska, Sylvestra Le Touzel, Anna Reynolds, Nonso Anozie, Trevor Cooper, Karina Fernandez, Philip Arditti, Viss Elliot, Rebekah Staton, Jack MacGeachin, Charlie Duffield, Ayotunde Williams, Stanley Townsend, Samuel Roukin, Caroline Martin |

| Director |

|

Mike Leigh — “Vera Drake” |

| Producer |

| Film4, Ingenious Film Partners, Summit Entertainment, Thin Man Films, UK Film Council, Simon Channing Williams, James Clayton, Gail Egan, David Garrett, Georgina Lowe, Duncan Reid, Tessa Ross |

| Distributor |

Warning: There are major plot spoilers in this review.

Director Mike Leigh’s most recent film is more of a character study than a story. It follows several events in the life of Poppy (Sally Hawkins), an elementary school teacher, whose strategy for dealing with life is to take the stance of happiness regardless of the circumstances around her. Think of “Happy-Go-Lucky” as a sort of secular version of Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking. The structure of the film is thematic, with each episode examining what happens as various people respond in various ways to Poppy’s insistent and persistent cheerfulness. Most, such as the book shop owner whose store Poppy visits in the film’s opener, find her disposition annoying, and whatever message a viewer derives from the film is probably dependant on whether or not one agrees with him (and Poppy’s acerbic driving instructor, Scott) or whether one sees a sort of nobility in Poppy’s attempts to meet the weight of Job with the wisdom of Pollyanna.

I didn’t see this film topping many (any?) end of year lists, but it sure felt like the film on all the lists that everyone was talking about. Of course, everyone is saying different things about it, which is what makes it so interesting. Thinking about “Happy-Go-Lucky” as a hot-button, provocative film is interesting, perhaps more interesting than the plot of the film itself, especially if your primary interest in film is in the narrative. People (at least the ones I’ve talked to) don’t seem to merely disagree about whether or not Poppy truly is happy; they seem to disagree passionately. Which leads me to the question of why we care so much whether Poppy is truly happy, passively-aggressively conflicting with those who aren’t, or just putting on a happy face for herself and remaining oblivious to how the world responds to her… For me, the answer is somewhat obviously the latter, and the real question becomes whether her ability to do so is healthy, unhealthy, or inconsequential.

If this argument is stacked, it may be because Scott, the antagonist who delivers the accusation that Poppy’s carefree attitude is calculated and contributes to his poisonous hatred of the world may be such a hostile and negative character that we reflexively go the other way just to disassociate ourselves from him. I’ve seen a lot of praise for Hawkins’s performance, and rightly so, but it is Eddie Marsan’s dead-on portrayal of habitual, toxic bitterness that creates the irresistible force to match Poppy’s immovable object on which the film truly depends.* His eventual explosion at Poppy is so obviously over the top, she is so obviously the convenient trigger rather than cause of his rage, that one can’t help but feel there could not possibly be even a seed of truth in his near-homicidal explosion of anger at Poppy.

No, there is not an actual homicide, but there is physical violence, and the threat of escalating violence in the final confrontation between Scott and Poppy is very real. Oddly then, I’ve been surprised at how many viewers I’ve spoken to profess to identify with Scott and take a certain measure of pleasure in the venting of his anger at Poppy. Perhaps there is something emotionally pornographic about depictions of anger and not just sex. That the threat of violence doesn’t come to fruition to the same degree it does in David Mamet’s “Oleanna” or Adriane Lyne’s “Fatal Attraction” doesn’t keep me from believing that this film, like those two (and, perhaps, Barry Levinson’s adaptation of Michael Crichton’s Disclosure) is as much about the venting of male rage at a world they feel is stacked against them than about the choices women make in the face of a raw deal.

A key difference, of course, is that the women that engender the rage in the earlier films participate in one degree or another in the humiliation of the men who finally strike out at them, which allows those films to couch themselves as revenge fantasies rather than misogynist ones. The woman is the symbol of his victimization not just the recipient of his wrath over it. In “Happy-Go-Lucky”, however, Scott’s rage clearly predates Poppy’s arrival on the scene; therefore, it strikes me as evident that his rage at her disposition is at least in part mixed with shame at his own realization that her conduct belies the flimsiness of the primary excuse rageaholics give to venting their anger—that it simply isn’t possible to control one’s disposition in the face of overwhelming circumstances.

That would suggest that the film is more on Poppy’s side than Scott’s, and I think it is. But I don’t think it is simplistic enough to suggest her response is a standard we should aspire to, that there is not something unsettlingly close to resignation in Poppy’s conduct. In that shade of difference between resignation and contentment lays the ocean between St. Paul saying he has learned to be content in all things and Dick Van Dyke (in “Bye Bye Birdie”) admonishing his fiancée (who actually has every right to be frustrated with him) to forget her troubles, come on and get happy.

Exhibit B in this argument is Poppy’s other male relationship in the film, with a young, handsome, male social worker who meets her because of her intercession on behalf of a troubled student and whisks her off to bed. Pay close attention to the morning after scene in which he expresses perfect contentment with living in the moment and is clearly thinking of their relationship exclusively in those terms. Is Poppy happier for having him in her life? Certainly, and his presence in her life is perhaps a reward meant to show that good karma comes around for those who refuse to give in to the self-fulfilling prophecy of bitterness.

Even so, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the film’s post-coda resolution, with Poppy and her friend in a rowboat on the lake literally going around in circles is dripping with irony. Perhaps it does not have the same hostile contempt that Poppy’s driving instructor has for her life, but it does (at least for me) still contain a strong whiff of, “If this is the life your philosophy has gotten you, what does that say for your philosophy?” Poppy is unquestionably happier than the habitually growling inhabitants of her circle, and if the film suggested that she was better off than she might be if she gave in to grousing, I could agree.

But—and this is a big “but” for me—there is a part of me that kept saying perhaps unhappiness is not always an inappropriate response to all situations. Just as physical pain makes Poppy seek out a doctor early in the film who treats the cause of her pain, so too can emotional pain and disappointment spur people to address the causes of their misery and perhaps have a better shot at true happiness. Narcotics are great for numbing pain and are sure as heck better than nothing when there is no alternative, but it is hard for me to see how any reading of the film that champions (rather than just sympathizes with) Poppy’s cheerfulness doesn’t eventually fall into the trap of assuming that true, deeper happiness is just an illusion and that the healthiest people are those who give over looking for it and settle for making the best of their solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short existence.

Is it better to settle? Is having a relationship that is limited to the current moment with no promise of (nor impetus for) anything further better than being alone? It’s not that I think there is anything wrong with clinging to those pieces of good within a sea of bad. It may actually be noble. But is there not something wrong with saying “peace, peace” when there is no peace? So the question becomes, which is Poppy doing?

My Grade: A

*Given that director Mike Leigh is rather famous for integrating extensive improvisation into his films, it is somewhat ironic that he was nominated for an Academy Award® for best writing, while Hawkins and Marsden were shut out of the acting categories. This nomination tells me that it is not just lay people or amateur film critics who have a hard time distinguishing the contributions of actor, director, writer, or cinematographer from one another and ought to be careful when opining about who should receive such awards.

Violence: Moderate / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½