Concerning Tolkien—3 Stars of “The Return of the King” and their differing responses to his books

by Jeremy Landes

Contributor

“Too often have I heard of duty,” [Eowyn] cried. “But am I not of the House of Eorl, a shieldmaiden and not a dry-nurse? I have waited on faltering feet long enough. Since they falter no longer, it seems, may I not now spend my life as I will?”

“Few may do that with honour,” [Aragorn] answered.

—From The Return of the King, by J.R.R. Tolkien

After seven years of filming Middle Earth, the world J.R.R. Tolkien created for his characters in The Lord of the Rings, you might be tempted to believe that some of the author’s strong moral and religious values, imparted to his characters, would rub off strongly on the actors. But you would be wrong in most cases.

Case in point, Aragorn, the warrior king who heads to Mordor in order to defend his race (mankind). In Tolkien’s books, Aragorn is a warrior who risks all to save the world from orcs and evil men—ruled by the power of Sauron, a dark lord. To accomplish his mission, Aragorn is required to take the mantle of kingship passed down to him by his forefathers. Fulfilling prophecy, like Christ, Aragorn is even able to heal his friends from wounds inflicted by powers of evil. Tolkien’s Aragorn (aka King Elessar) knows that injustice and evil, wherever it is taking place, must be corrected and rooted out—even when its victims seem small or insignificant, like hobbits. When King Theoden of Rohan and Denethor the Steward of Gondor refuse to fight, despite encroaching evil, Aragorn leads the charge and proves why he is destined to become king.

Viggo Mortenson

By contrast, Viggo Mortenson (an excellent actor who portrays Aragorn), at a recent “Return of the King” publicity meeting for the press, exercised his right of free speech (as a U.S. citizen) to criticize President Bush and U.S. leaders for “polic[ing] the world” and acting out of “self-interest” because of recent actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. Referring to U.S. leaders’ decision to invade Iraq despite the United Nations’ wishes, Mortenson says,

“Where we go wrong is saying that we do not have to adhere to the principles or ideals of the community of nations. We just spat on that.”

Many of Mr. Mortenson’s politically-charged comments throughout the interview showed blatant disrespect for those currently in authority, though he does not exclude himself from deserving some scorn. When asked whether he learned any life lessons that he could pass onto teenagers, he spoke about his 15-year-old son, who, he said, “has a healthy lack of respect for me.”

Ian McKellan

Gandalf the Grey (resurrected as Gandalf the White in the second film) is, without a doubt, the spiritual leader of the fellowship of the ring. Acting as a father figure to the two main heroes, Aragorn and Frodo, he promotes qualities of mercy and righteousness in contrast to his evil counterpart, the wizard Saruman.

In the first film of the trilogy, Gandalf encourages Frodo, saying,

“There are other forces at work in this world, Frodo, besides the will of evil. Bilbo was meant to find the ring, in which case you also were meant to have it. And that is an encouraging thought.”

Tolkien’s Gandalf clearly recognizes a more powerful force (though it’s never referred to as “God”) than himself, and he calls upon it when he’s in danger (listen again to the words he uses while facing the Balrog, a “demon from the underworld,” in the first film). Tolkien said that Lord of the Rings was “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.”

Sir Ian McKellan admirably performs his role as both Gandalf the Grey and White. Smiling, he related his perspective of Tolkien’s ideal, rural home for hobbits, The Shire, saying:

“I note, and with delight, that Hobbiton is a community without a church. There is no pope. There is no archbishop. There is no set of beliefs. There is no credo.”

Editor’s Note: This view is apparently related to McKellan’s professed faith in Atheism, and his active opposition to biblical Christianity, and his promotion and practice of homosexuality. In this context, he is quoted as saying:

“…think of the Bible as great literature rather than great history; great imagination rather than reliable witness. Whatever, it is not as a law book that I respect the Bible.”

“I have been reluctant to lobby on other issues I most care about—nuclear weapons (against), religion (atheist), capital punishment (anti), AIDS (fund-raiser) because I never want to be forever spouting, diluting the impact of addressing my most urgent concern; legal and social equality for gay people worldwide.” —Ian McKellen official Web site (2008)

Editor’s Note: To discover evidences that the Bible is a reliable book of history, see: Archaeology and the Bible, Creation SuperLibrary, and Bible and Theology Answers. Also available are articles on homosexuality and the Bible.

McKellan correctly states that Tolkien’s characters never worship gods in any fantasy religion. But both Tolkien, in his Forward to the books, “Concerning Hobbits,” and also director Peter Jackson (at least in the extended cut of “The Fellowship of the Ring”) take pains to discuss the beliefs and credos of the Shire—a place of “good tilled earth” where hobbits love one another almost as much as their beer and tobacco. (Note: During his interview, McKellan wise-cracked, “You think it’s tobacco they’re smoking, do you?”)

Despite Tolkien and Jackson’s Gandalfs consistent prayers throughout the book and films, including his reassurances to the hobbit, Pippin, that a glorious eternity awaits, if and when death should take him, Sir Ian McKellan maintains,

“I think what [Tolkien] is appealing to in human beings is to look inside yourself and look to your friends. [The characters] join the fellowship, they don’t join the Church.”

McKellan was not alone among his fellow actors, as they asserted their belief that Humanism and Environmentalism were Tolkien’s central story motifs, brushing past the author’s more Christian-based ideals that evil, in and of itself, exists, alongside innocence and pure beauty. If you would like to read more in depth about Tolkien’s Christian analogies, make an effort to find his book, On Fairy Stories.

Unlike C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia, where a lion represents Christ, one cannot assume that Lord of the Rings characters represent particular Biblical characters or that its stories are attempting to make a religious point. But the fact is that Tolkien, a devout Catholic, helped lead Lewis towards a saving knowledge of Christ. Characters in “Rings” live in a moral universe where absolute evil must be recognized in oneself and others, then either surrendered to or fought. This article’s purpose is not to chastise the film’s actors for not becoming Christians as a result of their involvement with Lord of the Rings.

It is written to help moviewatchers understand a fundamental difference between some of the actors (who may now be looked upon as heroes for the rest of their careers) and the characters they have played with excellence, putting aside their own creeds in submission to Tolkien’s views.

John Rhys-Davies

Actor John Rhys-Davies (a veteran of the “Indiana Jones” series), who plays the dwarf Gimli, showed some of his character’s boldness as he repeated some of his lines and made some comments concerning Tolkien’s beliefs that were unlike anything else expressed by other filmmakers and actors. Rhys-Davies said,

“I think that Tolkien says there are certain generations that will be challenged, and if they do not rise to meet that challenge, they will lose their civilization.”

Recalling his summer holiday in 1956 colonial Africa, Rhys-Davies remembers his father pointing to boats in the harbor that carried goods, which included African children sold into slavery. The father said to his son John,

“The United Nations will not allow me to do anything about it.”

Rhys-Davies’ dad went on to say,

“Look, boy, the next world war is not going to be between Russia and the United States. The next world war is going to be between Islam and the West.”

The eleven-year-old told his father,

“Dad, you’re nuts.”

His father maintained,

“Militant Islam is on the rise again, and you will see it in your lifetime.”

Rhys-Davies lamented the fact that his father has died, if only so he could tell his dad how right he was. Rhys-Davies went on to explain,

“Free democracy comes from our Greco-Judeo-Christian Western experience. If we lose these things, than this is a catastrophe for the world.”

Besides democracy, he named women’s rights and the abolition of slavery as excellent results of Western civilization that now need protection.

Whether Rhys-Davies was inspired by Tolkien to assert these creeds, or if he held these beliefs long before, the actor proved that he shared an understanding of Tolkien’s values that went beyond the author’s love for nature. John Rhys-Davies wrapped up his interview saying,

“If Tolkien has a message, it’s that sometimes you have to stand up and fight for what you believe in.”

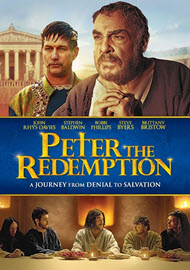

In 2016, Rhys-Davies was attracted to play the lead role of Peter in a dramatic faith-based feature film titled “The Apostle Peter: Redemption.” Stephen Baldwin plays the Emperor Nero.

Synopsis: “Tormented by his denial of Christ, Peter spent his life attempting to atone for his failures. Now as he faces certain death at the hand of Nero, will he falter again, his weakness betray him or will he rise up triumphant in his final moment?”

Rhys-Davies also worked on an audio drama titled “The Trials of Saint Patrick,” saying, “Patrick is giant. I am honored to have had a little part of bringing him to life.”

He also narrates the “Truth and Life Dramatized Audio Bible New Testament” (2010).

Rhys-Davies is quoted as saying, “I am very conscious of the debt that I owe to Christian civilization and to Christianity. Yes, and to Christians. Christianity is extraordinary. It is the most revolutionary affirmation of how people should live.”

See our REVIEW of “The Return of the King”, plus “The Fellowship of the Ring” and “The Two Towers”.

There are several books that go into rich detail concerning Tolkien’s themes and Christianity. While this Web site does not actively endorse any of these books, some that may be worth reading include:

Finding God in The Lord of the Rings by Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware

The Gospel According to Tolkien by Ralph C. Wood

Following Gandalf: Epic Battles and Moral Victory in The Lord of the Rings by Matthew Dickerson

Celebrating Middle-Earth: The Lord of the Rings as a Defense of Western Civilization, Edited by John West

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth: Understanding Middle Earth by Bradley Birzer