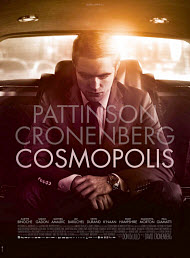

Cosmopolis

for some strong sexual content including graphic nudity, violence and language.

for some strong sexual content including graphic nudity, violence and language.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Mystery Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 49 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2012 |

| USA Release: |

August 17, 2012 (limited) DVD: January 2, 2013 |

money in the Bible

capitalism

billionaires

anti-capitalist riot

disgruntled employee

Did God make the world the way it is now? What kind of world would you create? Answer

ORIGIN OF BAD—How did bad things come about? Answer

a man’s perfectly ordered, doubt-free world implodes

forseeing one’s own murder

society’s anxieties and phobias

class differences

self inflicted gunshot wound

political refugee

obsolescence

loveless, dysfunctional marriage

extramarital affair / adultery

Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Robert Pattinson … Eric Packer Juliette Binoche … Dr. Ouelet Juliette Binoche … Didi Fancher Jay Baruchel … Shiner Kevin Durand … Torval Paul Giamatti … Benno Levin Sarah Gadon … Elise Shifrin Emily Hampshire … Jane Melman See all » |

| Director |

| David Cronenberg—“The Fly,” “eXistenZ,” “Eastern Promises” |

| Producer |

|

Alfama Films Prospero Pictures See all » |

| Distributor |

| Entertainment One |

Flannery O’Connor’s short story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” ends with a killer’s remark: “She would have been a good woman if somebody had been there to shoot her every minute of her life.” In her characteristic Southern Gothic style, O’Connor was saying that redemption is possible, perhaps inevitable, in those moments when darkness seems to have taken over.

David Cronenberg’s adaptation of Tom DeLillo’s 2003 novel, Cosmopolis is a story about destruction and redemption, a journey into the depths, and beyond the dark, to a place where a light can shine, a light that opens the eyes and sets the seer free. That first moment of freedom may come at the last moment of a character’s life, but it does come, and that awakening is more penetrating than the bullet that follows. Cronenberg, an atheist filmmaker, has a worldview different from the late O’Connor, a Christian writer, but both create a mood and a message that is similar. I’m sure Cronenberg would not agree that his films have a Christian message, but they have a moral context in which sin is held accountable and virtue ultimately, if unsteadily, prevails.

“Cosmopolis” is bracketed by two paintings, one in progress, one complete. The initial credits roll over a Jackson Pollock in progress, paint splattering in droplets and splashes on the surface of the canvas, and the final credits unfold on top of a Mark Rothko, a red square that looks as though it breathes blood. Art, specifically mid-twentieth century expressionistic art, figures incidentally in the story as a kind of multi-directed force, an unstoppable power, and a truth that flows not from reason and logic, but from an undefined, unchained energy. Today’s culture has been shaped not by art, truth and beauty but by technology, money and financial maneuverings, and these, according to Cronenberg, have brought about an almost irreversible social and personal decline.

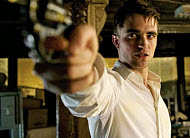

The film’s main character, Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson), is a 28 year old corporate executive who is worth billions. He lives a “master of the universe” existence in a sky high Manhattan condo that has two elevators, each equipped with a different speed and a different soundtrack. He is married to a blond ice princess whose family has as much money as he does, but their money, unlike his, is “old money”, and contrary to what some have said, that old money does wrinkle differently. At least Parker thinks so, and that bothers him. He loves her, but he resents her, and he is constantly unfaithful to her. He can’t hold on to his wife any more than he can hold on to the fortune that is quickly slipping out of his hands. He has gambled on the Korean currency, the Yuan, and is about to lose everything. Nonetheless, he seeks even bigger pieces of the pie. When an art dealer, played in serpentine fashion by Juliette Binoche … Dr. Ouelet

, recommends that Packer buy a rare Rothko that has come on the market, he turns his nose up, because he wants something bigger, namely the entire Rothko chapel that the painter constructed in Houston. When told the chapel is not for sale, that it belongs to “the people,” Packer replies: “if I buy it, it’s mine.”

Packer’s fortune is on the line; New York is in the throws of street protests (an Occupy Wall Street crowd, almost as unrestrained and unshowered as the real thing), and the President’s motorcade is making its way through town and clogging up traffic. For those of us who live in New York City, that is an average day, but, in this movie, it’s a seminal event. In the midst of the mayhem, Packer decides that he needs a haircut and has his limo driver and personal security guard drive him to the barbershop. The trip across town takes up the length of the movie. Having made that trip in my car a number of times, I can say that a couple of hours is about average for that course at that time of day. Packer’s stretch limousine is bigger than most New York apartments, and better equipped. Almost all the action takes place inside the vehicle. A number of visitors come and go, joining Packer in the limo for business meetings, deal pitches, philosophical discussions, moments of mourning, and even sexual encounters. A doctor comes into the limo to give Packer his daily physical examination, and the doctor administers a prostate exam while he is having a work related, well, sort of a work related discussion with a female finance officer. All this goes beyond common sense and good taste, but in the world of Cronenberg, and DeLillo, the higher point gets more shrift than just getting to the point. The prostate scene didn’t work in the book, and it doesn’t work here. Parker finds out that he has an asymmetrical prostate, and that becomes yet another theme; Parker’s misshapen organ is different from the norm, perhaps a bit freakish, and certain to be misunderstood. He may be a cold, take-no-prisoners corporate raider, but he still has a bit of the artist inside him.

The plot’s pace follows the limo’s which has two speeds: very slow and stop. The talk and the action go from disjointedly droll to just barely decipherable existential. In other words, most of what winds up on screen is off the wall stuff that is not so much intellectual as it just plain weird. It belongs to the David Lynch school of “I have no idea what any of this stuff means, so it must be brilliant” filmmaking. The tone is a departure for Cronenberg, whose last several features, “A Dangerous Method”, “Eastern Promises” and “A History of Violence” were engrossing dramas, easy to comprehend, and quite entertaining. With “Cosmopolis,” he has returned to the realm of his stranger works, “Naked Lunch”, “Crash” and “Spider,” but he has not made a complete U-turn. Despite his apparent detachment from what a movie audience outside the art house circuit might be looking for, Cronenberg does deliver. He is as much a showman as he is an artist. His heroes, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock, did not shy away from public acclaim or financial reward. They were dedicated to their art, but that did not stop them from raking in big bucks. Try as he might here, Cronenberg cannot break the bond he’s made with his audience. He has a unique touch, and he can please in a way that no other director can.

Packer’s limo is a grand machine, as well as a grand symbol. It may be a pod, or a womb, or a whale like the one that Jonah lived in for 3 days. It is all those things, but, ultimately, it is a funeral hearse that takes its passenger on a final journey. Packer begins his road trip as the owner of whatever lies ahead of him, but with each turn of the wheel he loses something. His car is throttled; people hurl rats at the windows; a protester throws a pie in his face; the barber mangles his hair; his designer clothes become tattered and stained, and, toward the end, he shoots himself in the hand. That bullet wound in the palm is also a symbol; the hole in his hand unites his suffering to that of a man who had a nail pierce his hand. Packer kills his security guard, but even during that shocking moment Cronenberg seems to toy with us by saying that such an act can be a revelation; Packer is putting away the things that protect who he is and what he owns. He is, in effect, giving up all that was once his. He is defiant and, unlike the rich man in Mark’s gospel, unwilling to go away sad, because he has many possessions. He is ready to meet his fate and to beg for redemption. To do so, he understands he must come forward not with everything, not even with something, but with nothing.

Packer meets his destiny in a tenement apartment occupied by Benno Levin, a man who once worked under Packer and who now resents him. Levin is seeking something. Whether it is judgment, retribution, attention or love is never clearly stated. He represents a universal nihilism that is a product of a culture based only on money and matter. Levin is played by Paul Giamatti, who breathes heavily and makes ample use of his trademark facial and ocular tics, but who ultimately misses the mark in creating a grim reaper whose spiritual force is in constant battle with his wounded humanity. Even putting a dirty towel over his head does not round out the image; it hides an actor’s face who seems tired and out of touch with the role. Giamatti’s cameo should have been the pivotal moment of the film, but the usually more than dependable actor falls sadly short.

Robert Pattinson seems an odd choice for the lead. I only saw a small part of the first “Twilight” movie, so I know little about his work or him, except for what I read in the tabloids. In the beginning of the film, he looks stiff and withdrawn, unable to do more than stare blankly and say his lines in a monotone that lacks irony, eeriness or dread. He sounds more like an NPR announcer than a corporate tycoon. Fortunately, he moves faster than his limousine does, and, by the film’s end, he manages to give a solid performance in what is not an easy role. Pattinson is handsome in a bland way, but something underneath that blank stare starts to speak with conviction and to break through what at first seems like a cement shell. The tears that come at the end are not those of fear or loss; they are tears that water and waken a face that has slept for too long.

“Cosmopolis” is the tale of one man’s road to perdition, but it has the elements of a salvation story as well. In exploring man’s depths, it often sinks, but ultimately it rises, and although it is strange and, at times, incomprehensible, it is never boring. David Cronenberg is still a first rate director, even if this is not one of his best. His classic movies will always stand up to Jackson Pollock’s drips and splatters.

Violence: Extreme / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Extreme

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

I’m not a person of faith and I hated this film. To the people here who are of faith I tell you to stay away. When you’re not bored you will be offended. To people here not of faith, stay away because when you’re not bored you’re clearly watching something else.

My Ratings: Moral rating: / Moviemaking quality: 1