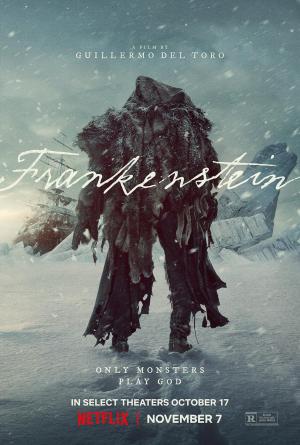

Frankenstein

for bloody violence and grisly images.

for bloody violence and grisly images.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Extremely Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Gothic Sci-Fi Horror Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 29 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2025 |

| USA Release: |

August 30, 2025 (festival) October 22, 2025 (limited theatrical) November 7, 2025 (Netflix streaming) |

Brilliant but egotistical scientist

Has death always existed? Why does it exist?

Learn about spiritual darkness

Nightmares in the film of a fallen demonic angel surrounded by fire

People consumed by revenge

What is eternal life? and what does the Bible say about it?

Director's worldview: Del Toro is an Agnostic, ex-Catholic

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Oscar Isaac … Victor Frankenstein Jacob Elordi … The Creature Christoph Waltz … Harlander Mia Goth … Elizabeth / Claire Frankenstein Felix Kammerer … William Frankenstein Charles Dance … Leopold Frankenstein David Bradley … Blind Man Lars Mikkelsen … Captain Anderson Christian Convery … Young Victor Frankenstein Nikolaj Lie Kaas … Chief Officer Larsen Kyle Gatehouse … Young Hunter Lauren Collins … Hunter’s Wife Sofia Galasso … Anna-Maria Ralph Ineson … Professor Krempe See all » |

| Director |

|

Guillermo del Toro |

| Producer |

|

J. Miles Dale Guillermo del Toro Scott Stuber Bluegrass Films Demilo Films Double Dare You [Mexico] |

| Distributor |

“Each person is tempted when they are dragged away by their own desire and enticed. Then, after desire is conceived, it gives birth to sin; and sin, when it is full grown, gives birth to death.” —James 1:14

“For everyone who does wicked things hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works should be exposed.” —John 3:19-21

“There is no horror that has not been consecrated somewhere.” —Marquis de Sade

Mary Shelley was a writer at odds with herself. The Enlightenment philosophy that man can exist and flourish solely by his own intelligence and will intrigued Mary and her circle of writer friends, but its ideals clashed with what she knew about man’s fallen nature. She touted the French Revolution even though she couldn’t have been too surprised by its excesses. She read Milton, Plutarch and Goethe as well as Rousseau, so she must have found herself at an intellectual impasse. An unhappy impasse.

Shelley’s novel confused me both times I read it. I admit that her seminal book is a classic, but I step back from calling it a great novel. It’s a grand and resounding mythical allegory, but I can’t bring myself to say it is a great work of art. The contradiction between man as a creature made in God’s image and likeness and man’s fall from God’s grace is not resolved in “Frankenstein.” A so-so novel was published, but a great horror myth was born.

Like so many filmmakers before him, director Guillermo del Toro plays around with the convertible plot elements of “Frankenstein” and with the amorphous personalities of its characters. He reshapes Shelley’s myth to fit modern tastes, as well as his own artistic and political sensibilities, and in the process, makes a hash of most of it.

I read a few recent reviews that claim the film, unlike other interpretations, remains mostly faithful to the book. Um, no. It’s the least faithful adaptation I’ve seen. This version, ladled full of body parts, lacks the building blocks that a story about the process of constructing something needs. It requires organic matter to ground it and a guiding spirit to move it. Like its sewn together monster, its flesh is wasted and cold, while its spirit never animates. It has atmosphere galore (the production design is by Tamara Deverell; the costumes are by Kate Hawley) but, like its well-toned monster, it has no soul.

The overly long film (2½ hours) wavers and waddles but does not come together until its closing scenes. In the end, the script (also by del Toro) rejects Shelley’s ending and gives us a more hopeful, and more apt, conclusion. Light breaks through the shadows and forces death not to disappear, but to take a pause. Forgiveness, understanding, and grace push back the wages of death. It is the only time the two leads, Oscar Isaac, as Victor Frankenstein, and Jacob Elordi as the monster, are allowed to lift off and almost soar. Before then, both actors are muffled, hooded and sidelined by scenery glut and a score that doesn’t accent the action as much as shout over it.

Isaac plays Victor Frankenstein as a repressed and fiery Jacobin, a Robespierre-like figure who is convinced of and wedded to what he sees as his innate virtue. Isaac’s stabbing stare is often hidden under a wide brimmed hat and a hairstyle more suited to a man fitting horseshoes than to one with dual titles: baron and professor of medicine. The strand of hair that falls over the eye during the pivotal “it’s alive!” scene worked well for Colin Clive in James Whale’s 1931 “Frankenstein” because in that moment it revealed just how manic, obsessed and crazy the doctor truly was. Isaac repeats the look, but its impact is more comic than ghoulish.

Elordi is physically imposing but oddly costumed in ragged capes and “Rocky Horror”-style gold shorts. He lets his large body go lax and gawkish, his gradual adapting of coordinated movements telling a story that his words cannot. He can shift from tender to terrible in short order, but he falls short of conveying or sustaining a sense of the monster’s constant danger.

Like its source material, “Frankenstein” shifts points of view. The film begins on a frozen sea. Ship captain Robert Walton is leading an expedition to the North Pole, a mission as dangerous and doomed as Victor’s own journey. Walton comes upon a wounded and almost frozen Dr. Frankenstein who has pursued his creature to the far end of the Earth to once and for all destroy “the wretch” he has made. The man against nature setting has the grandeur and ferocity of a Caspar David Friedrich painting, the film’s only sequence in which design, cinematography, editing and directorial mettle come together and create a worthy and watchable adventure of revenge, pursuit and ultimate destruction equal to the final moments of Stroheim’s “Greed,” a masterpiece about human revenge and pursuit, or even to a more mundane cat and mouse tale such as “The Count of Monte Cristo.” (I like almost all versions of that film, so I hope Del Toro doesn’t remake it.)

In the next segment we are taken back in time to Victor’s childhood, a mostly unhappy time for him. His mother with whom he has a close, perhaps too close, relationship dies suddenly. Victor is then reared by a stern and punishing father (Charles Dance) who beats his son’s face with a metal rod when he answers his anatomy questions incorrectly. The father does not strike the boy’s hands because those will someday be needed for performing surgery. The preteen violence which interestingly leaves no physical scars on the adult Victor’s face is the catalyst for Victor’s controlling, neurotic and grandiose nature which comes into full flower when he inherits his father’s estate and becomes a preeminent practitioner and lecturer of medicine.

Death has been a cruel reality for Victor as it had been for Mary Shelley (her mother died after giving birth to her; three of Mary’s own children died before reaching adulthood; her husband’s first wife committed suicide) so his goal in life is a crusade against death. He is determined not to preserve life but to reanimate it from tissue that had already died. It is here that Del Toro steps into a swamp. His post-Freudian approach to character in a decidedly pre-Freudian Romantic period is bewildering and ultimately fatuous. His Victor is less tragic than self-destructive, his motives being, as the monster tells him, “all about will, YOUR will.”

Victor commits awful acts with a bonhomie that is chilling. He has no second thoughts about selecting his future laboratory cadavers from line-ups of men waiting to be executed at the gallows, seducing his brother’s fiancée (Mia Goth, beautiful in multiple shades of chiffon and tuille but emotionally inert), posing as a priest in a confessional, and shirking responsibility for deaths that he himself brings about. There’s more to Victor’s abnormal mindset than a troubled childhood. He acknowledges a dark angel, and Del Toro presents one in the form of a fiery armed sculpture, but the director shies away from any spiritual component to evil and to man’s saying yes to that force.

Dr. Frankenstein works feverishly in his lab. He puts his creature together with lots of biological skill but no clinical sense. The amputations, dissections, and disposals of surplus organs are as stomach churning as any image in Andy Warhol’s “Flesh for Frankenstein” which despite that 1973 film’s amped-up gore, originally shown in 3-D, had a sense of humor and an understanding that power and perversity often go hand in hand.

The rationale for injecting a living force into something that is not living has never been logical in any kind of scientific sense, although Shelley’s application of electricity did elicit a charge in the early 1800s when the phenomenon was still undeveloped but had the mystique of inciting a new kind of revolution and liberation, both tenets of Enlightenment thought. The subtitle of Shelley’s work was “A Modern Day Prometheus,” Prometheus being the Greek titan who stole fire from the gods to give to man. Electricity might have then been seen as a new fire that had the potential for liberating man from an old-world order, and from God.

Del Toro tries to align science with economics in what amounts to a throw-away plot line. Victor’s experiments are funded by a businessman named Harlander played by Christoph Waltz. The scenes between the two are a muddle of theses about how money and greed corrupt everything from science to humanity to life itself, but all DelToro is doing is wasting his own movie, and casting Waltz as Dr. Frankenstein’s antagonist-enabler is a major blunder. I tend to find most of Waltz’s performances clownish and self-aggrandizing. Whenever I see him on screen, I think of a performer from an old Vaudeville circuit plucked off the stage and dropped onto a movie set to toss off lines and follow them up with a side-step or a soft shoe. Only in the film “Georgetown,” which Waltz directed did his over-the-top style work to a film’s advantage.

I have no idea what this Victor Frankenstein is talking about when he tries to explain what he is cooking up in his lab. It has something to do with delivering an electric charge to the body’s lymphatics and to its autonomic nervous system. Peter Cushing made such inane theories a lot more digestible in “The Curse of Frankenstein” (1957); in fact, Dr. Mornay’s explanations of harvesting and implanting a “more obedient brain” in “Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein” (1948) carries more weight than anything Del Toro’s scientist spews.

When his experiment is completed, Victor concludes his experiment to be a failure. He retreats to his private quarters and falls asleep. He awakens to his newly manufactured and freshly charged creature standing before his maker’s bed, another Freudian allusion that hangs awkwardly in the air, as if to ask, “okay, what now?”

In the following segment the creature abandons the maker who has rejected him, sets out on his own and attempts to assume an identity. He is shunned by the humanity he confronts because, as a monster, he is horrible to behold, belonging not to the race of man, but “made by some manner of devil.” Nonetheless, he is resplendent with vague mythical qualities of superhuman strength, indestructible healing powers and an intelligence that allows him to learn quickly and to assess human nature.

He finds his creator’s discarded lab notes and from those he can put together the story of how his creator made him and how that maker came to despise him, a sad realization indeed. He, like all of us, finds meaning in his life by searching for his Creator and yearning for a relationship with the One who made him. Like those other great voyagers of myth, Odysseus, Horatio Hornblower and Peter Pan, we seek knowledge, love and happiness through things that bring us closer to the infinite. Life would be a mere folly if we ignore that quest. The poor monster who has what seems to be life eternal, boundless strength, and control over nature lacks the one thing he wants and seeks: a soul. He looks for one by asking his maker to create a companion for him, something Victor refuses to do.

Again, this is a deviation from the book, and perhaps it’s for the best. Del Toro’s creature is, unlike God’s, meant to be alone. And the last thing the film needs is one more body harvesting and laboratory dissection scene.

This new version mostly flounders, but it does start to swim in its closing moments. Both the lead actors come alive as though they sense that their lines finally make sense, and so do their characters. Elordi’s monster is no longer Shelley’s. He is on his way to being human, to being redeemed. He is the child of “Rosemary’s Baby” made tender by a mother’s gaze and a hand softly rocking its cradle. There is understanding, forgiveness, and hope, none of which came through in the film’s earlier, mostly inert, scenes. The ending is elegiac, almost operatic, in the way it warms the heart and stirs the soul. The rest of the film could have used more of that light and tenderness, and acknowledged that despite our fall, grace is there for the taking. Especially when we least deserve it. And least expect it.

- Violence and Gore: Very Heavy

- Nudity: Moderately Heavy —male nudity, rear and upper

- Language: Moderate

- Drugs/Alcohol: Moderate

- Wokeism: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.