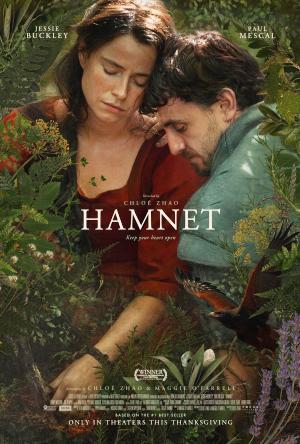

Hamnet

for thematic content, some strong sexuality, and partial nudity.

for thematic content, some strong sexuality, and partial nudity.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Biography History Drama Adaptation |

| Length: | 2 hr. 5 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2025 |

| USA Release: |

December 5, 2025 DVD: March 3, 2026 |

William Shakespeare period drama tragedy

The film’s largely fictional story dramatises the marriage between Anne Hathaway (Agnes Hathaway in the novel and film to avoid confusion with the actress with the same name) and William Shakespeare, and the impact of the tragic death of their 11-year-old son Hamnet on their relationship, which inspired Shakespeare's play Hamlet.

Daughter of a forest witch

Mysterious cave

Pregnancy followed by marriage

Childbirth

Loss of ability to predict the future

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Jessie Buckley … Agnes Shakespeare Paul Mescal … William Shakespeare Emily Watson … Mary Shakespeare Noah Jupe … Hamlet Joe Alwyn … Bartholomew Hathaway David Wilmot … John Shakespeare Jacobi Jupe … Hamnet Shakespeare See all » |

| Director |

|

Chloé Zhao |

| Producer |

|

Sam Mendes Steven Spielberg See all » |

| Distributor |

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.” —Matthew 5:4

“Jesus wept.” —John 11:35

“Madame, how do you like this play?”

“The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” —Shakespeare, Hamlet Act III Scene II

“Hamnet” opens with an image of a forest tree, a big tree, whose trunk and roots form a womblike shelter. Inside that hollow, the film’s heroine, Agnes (Jessie Buckley), doesn’t so much shield as expose herself. She offers her being up to nature’s untamed but life-giving forces. Those elements of earth and sky, be they cold, rain, or mud, become the givers and keepers of all that is good in the world while serving as guardrails against the threats posed by human progress and societal norms.

It’s a take, an irrational and ultimately mindless one, on Elizabethan sensibilities as well as today’s, a melodramatic dance-around with overlays of D.H. Lawrence, Joe Orton, and Sam Shepard.

Ann gives birth to her first baby in that tree trunk, fathered by a man she meets in the forest, a man who appears to be more a part of the forest than of any social structure. Like her, he is a free spirit, a sprite, perhaps a fairy plucked from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” The two romp amongst trees, glens and a few indoor spaces as well. Hence, the child.

They marry and live domestically in an arrangement that suits wife but not husband. There is a second pregnancy, a twin one, that is more problematic than the first because, as we are given to believe, it occurs not outdoors in a natural habitat but inside a man-made one, with midwives instead of hawks in attendance.

The children’s father is a young playwright named William Shakespeare. Headstrong, ambitious and often contrarian, Will retreats to London to write, direct and act for the new Globe theater while Agnes stays at home to care for the children.

While Will is away, tragedy ensues. Two of the children develop febrile illnesses and one of them dies. The remainder of the film focuses on the rift that develops between Agnes and Will, the grief that they both endure, and the influence of that anguish on Will’s writing of a play he would call “Hamlet.”

Some of the movie is moving, even enriching, but it turns grating when its sentiment dissolves into sentimentality. I admire a lot of what I saw in director Chloe Zhou’s earlier work: the balletic minimalism of “Rider,” and the warm naturalism of the non acting performances in “Nomadland,” at least during the scenes in which those actors weren’t blocked out by Frances McDormand’s heavy handed, almost oppressive presence.

In “Hamnet,” Zhou is working with, aside from several admirable child actors, a cast of professionals. I liked Jessie Buckley in “The Lost Daughter,” and “I’m Thinking of Ending Things.” The plots of those movies were hard to pin down, but Buckley’s performances were spot on; her persona navigated and distracted from, those film’s confusing twists. But in “Hamnet,” I found her performance exaggerated and at times insipid. Her portrayal of an unhappy wife and mother feels cajoled, almost as if it was beaten out of her. The labor, resuscitation and even the egg cracking scenes feel oppressive and mean-spirited. A story of loss and grief could use more anguish and less anger, more silence and less teeth grinding or as Will would say and was writing at the time, “more matter and less art.”

Buckley is fortunate to be supported by an array of actors who make the most of their small parts. Emily Watson as Will’s mother and Joe Alwyn as Agnes’ brother, are both short on words but full of quiet intensity. During their abbreviated scenes, they stand tall next to their leading co-stars.

Paul Mescal, whose recent performances in small films such as “All of Us Strangers” (2023) and “The History of Sound” (2025), conveyed sadness and gloom in a spartan style that helped carry those films. I get why he was cast here. He’s endearing in a laid-back, nontoxic way but he flubs the part of the Bard when it calls for his character to take a stand. There is one scene in which Shakespeare instructs an actor on how to perform the “get thee to a nunnery” speech in Act III of “Hamlet.” Mescal, in that moment, opens up and is onto something. He channels grief, guilt and anger into believable human reactions and gives those emotions some real juice. But those batteries quickly stop revving. They die out when Zhou has him give the “to be or not to be” soliloquy as a prelude to a possible suicide, one staged on the edge of a bridge. Watching Mescal’s maudlin aberration of some of the best words ever written in the English language made me glad I wasn’t anywhere near a bridge while listening to it.

I felt that the closing scene of the film which is also the closing scene of Shakespeare’s play was overwrought and inconsistent with the play’s unyielding and haunting climax. As the bodies pile up on stage, Zhou would have us believe that unbearable, inconsolable grief can be, if not conquered, at least ameliorated, by the power of art. I found the display more stultifying than stirring even though the actor who played the actor who played the first Hamlet (Noah Jupe whose younger brother Jacobi Jupe played the doomed 11 year old Hamnet Shakespeare) was captivating. Zhou appears to be telling us, actually teaching us, that life may bring us harm, but art is there to revive and to restore us. Healing comes not from our own sense of nature’s laws, not from grace, and not from God. Redemption is to be found in the promises of a select elite who sees, and knows, what is best for all.

“Hamnet,” like so many contemporary films, imposes modernity’s sentiments and values not just on classical works but on history itself. Not much is known about the private lives of William Shakespeare and his wife, Anne Hathaway, but this life and times interpretation lacks a sense of the vitality, vibrancy, and verve that must have characterized Elizabethan England.

There was a keen religious sense during the young days of the country’s Reformation but any acknowledgment of that is tossed aside in favor of imposing a modern ethos of environmentalism, transcendentalism, and a spiritualism that borders on the occult (early on we are told that Agnes is the “daughter of a forest witch.”)

Shakespeare was not a naturalist. Or a Darwinian. Or a spiritualist.

His words were Christian. So, most likely, was he. One might also call him a prophet of sorts, at least a literary prophet, one who predicted what would happen to a world that turned on its values and on itself.

“Of the world’s ransom, blessed Mary’s Son,

This land of such dear souls, this dear, dear land…

That England, that was want to conquer others, hath made a shameful conquest of itself …” —Shakespeare, “Richard II,” Act II Scene I

- Occult: Moderately Heavy

- Wokeism: Moderately Heavy

- Sex: Moderate

- Violence: Moderate

- Profane language: Mild

- Vulgar/Crude language: Mild

- Nudity: Mild

- Drugs/Alcohol: Minor

Q & A

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

Does God really exist? How can we know? If God made everything, who made God?

Does God really exist? How can we know? If God made everything, who made God? What if the cosmos is all that there is?

What if the cosmos is all that there is?

This is a film from beginning to end made by outsiders and about outsiders. The director Chloe Zhao, born in mainland China, only started to learn English at age 14. She is an “outsider” to the “Shakespearean tradition.” The screenplay of the film was co-written both by the author of the original book “Hamnet”—Maggie O'Farrell—as well as by the film director Chloe Zhao. The author O'Farrell considers herself to be an “outsider” within her wider community of Northern Ireland. The main actor and actress in the film—Paul Mescan and Jessie Buckley—are from the nation of Ireland—from a culture which has stood outside of English culture for so many centuries, for a variety of historical and religious reasons.

Within the film “Hamnet” itself, Shakespeare is from the English countryside and thus as an outsider finds his career in London. His wife, who remains in the countryside, is an outsider due to her connection to the native healing traditions and ancient ways of England.

The center of the film is coming to terms with death and grieving. In a recent interview the film director Chloe Zhao said: “I have been terrified of death my whole life. I still am. I’ve been so afraid I haven’t been able to live fully. I haven’t been able to love with my heart open because I’m so scared of losing love, which is a form of death. When you’re in your 40s, a midlife crisis is the best thing that can happen to you, because you’re on your way to a rebirth.” The film is like her personal meditation on the themes of death and loss, and tying it in the cultural meaning and significance of Shakespeare.

The film has layer upon layer of symbolic meaning. Spirituality is difficult to put on a screen, but the film “Hamnet” walks the fine line of making a spiritual understanding comprehensible. The film director has said that she has grown from an atheistic background as a child to a more encompassing understanding that there is something greater in life. Her answer to loss and grief in the film is that each person is part of a greater whole and to trust the unfolding of nature around us. I could imagine some viewers of the film could be drawn away, towards the director’s “nature is all” philosophy, vs. others being drawn to further look for the Lord of all creation.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5