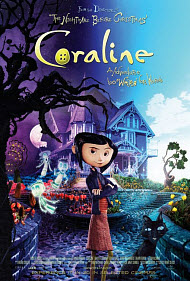

Coraline

for thematic elements, scary images, some language and suggestive humor.

for thematic elements, scary images, some language and suggestive humor.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Teens Adults—not for kids |

| Genre: | Animation Fantasy Horror |

| Length: | 1 hr. 40 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

February 6, 2009 (wide—2,100 theaters) DVD: July 21, 2009 |

Sin and the depravity of mankind

Fear, Anxiety and Worry… What does the Bible say? Answer

How can I help my child to trust in God’s care when she is afraid at night? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Dakota Fanning … Coraline Jones (voice) Teri Hatcher … Mel Jones / Other Mother / Beldam (voice) Jennifer Saunders … Miss April Spink / Other Spink (voice) Dawn French … Miss Miriam Forcible / Other Forcible (voice) Keith David … The Cat (voice) John Hodgman … Charlie Jones / Other Father (voice) Robert Bailey Jr. … Wyborne ‘Wybie’ Lovat (voice) Ian McShane … Mr. Sergei Alexander Bobinsky / Other Bobinsky (voice) See all » |

| Director |

| Henry Selick — “Monkeybone” |

| Producer |

| Laika Entertainment, Pandemonium, Claire Jennings, Harry Linden, Bill Mechanic, Mary Sandell, Henry Selick, Michael Zoumas |

| Distributor |

“Which mum is more fun?”

“Coraline” is a film by Henry Selick (“The Nightmare Before Christmas”) based on the award-winning children’s book by Neil Gaiman. The story concerns an 11 year old girl whose mother and father move into a secluded house in the country. In the attic of the house lives an eccentric man who trains mice and in the basement live two eccentric and aged former actresses who have dogs. Coraline is bored, her parents have time only to type on their computers, and so Coraline discovers her own adventure.

The film is not only shot in stop-motion animation, like “James and the Giant Peach” and “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” but it is also filmed in 3D, though the use of the technology is not as striking as in the movie “Beowulf” (2007). The texture of the film is interesting, but there are no innovative concepts. The idea of an alternate world behind a door or mirror, we have seen before in Alice in Wonderland and in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In an interview, Henry Selick acknowledges as much, saying:

“I call the film and the book sort of a combination of Alice in Wonderland and Hansel and Gretel.”

What is unusual about this story, both book and film, is the moral darkness of the universe which Coraline inhabits. The moral of the film can best be summarized as “Be careful of what you wish for” or, as Coraline in the book says, “What kind of fun would it be if I just got whatever I wanted?” (133). Coraline’s boredom leads her into a dangerous parallel world in which there is an Other Mother and an Other Father who are attentive to her, cook great meals, and have a home full of fantastic toys and moving furniture. They also have buttons for eyes.

Neither the plot nor the setting are the most important parts of the movie, as concerns Christian parents. Rather, of concern is Neil Gaiman’s conception of an alternate world in which the functioning domesticity of a mother who cooks and a father who works is a kind of hell. In the book, the Other Mother punishes Coraline:

“You needed to be taught a lesson, but we temper our justice with mercy here; we love the sinner but hate the sin” (98).

The speech is clearly a slam at the kind of home where mothers cook and fathers work and parents speak of “sin” and “sinner” and “mercy” and “justice.” It is the kind of home that atheists imagine Christians live in: a Stepford Family reality of puppet people with no creativity or individuality.

The most disturbing thing about the movie is the tone of the relationships. Henry Selick adds a boy character named Wybie, short for Wybourne, whose name Coraline mockingly transforms into “Why-were-you-born?” In every relationship in the movie, the female character abuses the male. The real mother dominates the real father, the Other Mother ultimately destroys the Other Father, the grandmother controls Wybie, and, worst of all, Coraline strikes and abuses Wybie in both the real and the Other World. Wybie is a trodden-down character in both worlds, who slouches, is slavishly deferential to Coraline, and is clearly less of a person than she is. What this accumulation of images constructs is a moral universe in which the family or community are subservient to the demands of a tyrannical individual.

The fact that Ramona is one of the characters Coraline reads is not surprising, in the sense that Coraline comes across as a spoiled child to a Christian audience. To a non-Christian audience she is supposed to seem confident, charmingly rebellious, and, above all, equal to the adults. It is an atheistic view of family in which moral authority begins with the child, flows through the mother, and ends at the father: a conscious inversion of a Christian family model.

Coraline’s aggression is supposed to be indicative of her assertiveness, but in a social universe where every woman is cruel or cold, Coraline comes across as an extension of the good and bad mothers. What the female characters have in common are an abusive streak that is either slight or extensive, but which is present in all three. Gaiman’s perverse view of relationships may have to do with the fact that he is reacting against the Disney model:

“Have you ever had to watch The Disney Channel, and the kind of plots that are deemed acceptable on that channel? Let me give you an example: Somebody thinks that everybody’s forgotten their birthday, but they haven’t, because they were planning a surprise party all along! And everybody loves everybody, and then they hug. It’s almost like pornography [everybody laughs]. It presents this vision of an impossibly hospitable world which children know doesn’t exist.”

http://hollywood-animated-films.suite101.com/article.cfm/interview_neil_gaiman_on_coraline

Any artist who sees happy relationships “like pornography” will certainly see actual pornography in a different light. Gaiman’s book sexualizes the relationship between Miss Pink and Miss Forcible and shows them in relatively modest circus outfits. However, Henry Selick extends that content and portrays a naked Miss Forcible as a strip dancer wearing a sequined thong and stripper’s pasties on impossibly huge breasts. The children in the audience cried out their disgust in tones of amusement and surprise, as if to say, “So that’s what they look like without any clothes!” It is a deeply misogynistic image which will elicit disgust in any Christian viewer, regardless of age.

Gaiman’s book is not as dark as Selick’s vision, and the illustrations by P. Craig Russell on page eight show images of the movies “Totoro” (1988) and “Babe” (1995), as well as partial covers of Lily’s Ghosts (2005) by Laura Ruby, The Wall and the Wing (2007) by Laura Ruby, Ramona and her Mother (1990) by Beverly Cleary, and Warriors: Into the Wild (2003) by Erin Hunter. These references are left out of the movie, which oddly converts Coraline into a hollow mental and spiritual shell who desires only physical experience.

From a story standpoint, the book is a hodge-podge of incidents and images. Gaiman is famous and has the ability to trade on the brand of his name. He can put almost anything on the market, and it will sell. For example, this quotation of how the book came to be published is revealing:

“And I had a small, Wednesday Addams sort of daughter who liked stories with strange mothers and cellars and dank places and creepy stuff, and so I started to write her one. And then I realized I hadn’t written anything for 5 years, and I’d better get a contract, otherwise it would never be finished. So I sent it to a publisher, and my editor called me up and said, ‘So what happens next?’ and I said, ‘If you send me a contract, we will both find out.’”

In other words, he didn’t have a story outline. Incidents just morphed into a kind of tale over a period of five years without any underlying moral or an awareness of absolute good or evil. In a real myth, such as those written by C.S. Lewis or J.R.R. Tolkien or George MacDonald, there is absolute good and evil, and they are represented not only by things and characters, but by living ideas which must be confronted by the mind and heart, as much as by the body. In “Coraline,” the evil is a mother who cooks and cleans and the good is a rejection of that mother. There is no good idea, just a mode of rebellious behavior that arises out of boredom. Such boredom stems from children having a sense of entitlement to be entertained and a self-esteem which is always fed flattery and praise. This comes from having too many things and not too few things to do.

In “Coraline” there is no good; there is only evil. Coraline’s malicious behavior toward Wybie is portrayed as independence. In the end of the book and movie, Mr. Bobo says “The mice tell me you are our savior.” But how has Coraline saved anyone? The parents now dig in the garden instead of type on their computers, but Coraline has not undergone any change. It is her parents who must change in order to accommodate her. She has not become a better person toward Wybie, less selfish in her demands, or less self-centered in the way she views the world around her. It is, literally, a world without God, in which the self is its own god and which must be fed experience in order to be fully alive.

“Coraline” is a bad movie for children and a disturbing movie for adults. The horror of it comes not from the plot, which is common, but from its nihilistic attitude. This view sees human relations as power struggles which can only be resolved by an exercise of will, and it sees life as an existential wasteland that has no intrinsic meaning, but what we can give to it ourselves. As art, it is a diminished thing without light, while its truest love is of the darkness in all things. Some people may be misled by the bright tone of the voices in its real world to think it is an “uplifting” movie, but underlying that tone is a spiritual emptiness which inhabits the characters, the setting, and, it seems, the movie’s creators.

Violence: Moderate / Profanity: None / Sex/Nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

I just DIDN’T get that from this move; in fact, I liked it quite a bit.

I think the main review of this movie is a bit flawed in its portrayal of the movie. True, this movie was taken from a novel (which I have not read) that apparently says some pretty pathetic things about the truth of sin and morality, but they just weren’t a part of the movie screenplay. It’s also true that a book story made into a movie story may indubitably reflect a bit of the author’s original message, but if the book had anything really insidious to say (as it may have), none of it made it into what you see through your 3-D glasses. I wouldn’t ever read the book because of what it says on page 98, but the fact remains that neither this idea nor similar insidious ideas were in the script.See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

The movie Coraline is about a middle school girl who’s parents have moved her across country from Michigan to a small town in Oregon. Coraline is an only child to parents, both writers, who work from home. They move into a old, large, rented home that has a “haunted” past.See all »

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 4

Interestingly, none of these things happened in “Coraline.” Is it creepy? Sure, but all the creepiness is implied. Is there a 98 year old woman with size D breasts? Yes, but that may be the scariest moment in the film.See all »

Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

This film is not for children because of that and other moments that are genuinely frightening. This movie also has problems with its pacing. It tries to be funny, dramatic, suspenseful and emotional. It just doesn’t really work. Despite its many downfalls, “Coraline” is still fairly entertaining and is worth a one-time-see for adults and teenagers.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moviemaking quality: 5

Morally speaking, the film isn’t right for youngsters. Putting a half-naked, elderly woman in a children’s film with an incredibly huge chest is not appropriate, and I don’t care if it is within the context of Sandro Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” (imagine an 80-year-old Dolly Parton). Most children under 10 haven’t taken art history courses. I do agree with the reviewer on the grounds that the movie has a bit of a nihilistic feel to it. Plus, it can be scary to younger kids. It even freaked me out a little bit. I guess one could say that this is a horror movie for the younger set. The one good thing about this movie is that Coraline realizes that she would much rather stay in her boring life than the really fun life…after being threatened with bodily mutilation.

In conclusion, I think parents are better off renting some old school Disney DVDs like Snow White or Cinderella. Heck, “Snow White” was just as dark as this, and it didn’t have to rely on human mutilation as a plot.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

To me, she seemed like a child desperate for attention and love from her parents. The other mother offered her that love and attention. To me the other mother was like a demon. It had created the illusion of what Coraline wanted to tempt her to stay in a world that Coraline knew wasn’t her rightful home. Much the way we are tempted in real life. Coraline in the end rejected this view, but the movie also showed the fate of those who do not reject it, and stayed stuck in that world by having their eyes, the biblical window to the soul, taken away and replaced by doll buttons, another aspect I considered highly fascinating. In the end, I saw that Coraline had not changed much, but she did seem less demanding and happier, not because her parents were giving her everything she wanted, but because they were spending time together as a family, doing a family activity.See all »

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 3½

I enjoy some of Gaiman’s other books, like “Anansi Boys,” “Neverwhere,” and “Stardust,” and think he is a very talented author. I don’t know what his religious beliefs are, but I think he has a definite grasp on what is evil.

I am not a big fan of anything creepy or in the horror genre. So when I read Coraline, I admit, I was a little freaked out. The Other Mother is a very evil, sinister character. And it’s not because she cooks or has a “traditional” role—not at all. It’s because she wants Coraline. Like a spider wants a fly. See all »

A month ago (25 Dec 2020), I handed myself over to Jesus. Not the circumstances of my life, I handed myself over—I received the forgiveness he’d paid for on the cross. It prompted me to look through my book collection, music collection, and movie collection. What we feed our souls matters.

Gaiman emerged as a problem. He is profoundly amoral, operating to nothing more than “rule of cool,” although he often sinks to plain shock value: such as in hIs short stories “Snow, Glass, Apples,” and “The Problem of Susan.” I can’t think of many instances in his stories where any characters act out of a desire to help another person, rather than helping someone because it will enable them to achieve their own ends: the three trapped souls in the Other Mother’s world receive help from Coraline mainly because doing so helps her to escape and get her parents back. There is no indication that she would have helped them if it had not been necessary.

We learn no profound moral lesson from Coraline’s behaviour. The film is not a problem if we go by ratings, in fact, there are still numerous films in my collection that have higher ratings. Last Emperor has nudity and sex, albeit not very in-your-face, and No Country for Old Men has some nasty violence and language. But both those movies have moral standpoints. They don’t hit you over the head about what’s right and wrong, thereby demonstrating good storytelling. But they do show you the difference, as we see the consequences of characters” actions. Coraline muddies the difference between right and wrong to the point of non-existence. It’s just one nasty female taking down another by outsmarting her, and helping others if there is something to be gained from doing so.

I won’t deny the coolness of the visual aesthetic, the way the other world becomes obviously a simulation and sends one back to the “hub,” the way the other mother becomes increasingly insectile, Coraline’s street smarts, the cat who can slip in and out of worlds, the dancing mice leading Coraline to the tunnel, etc. But that’s exactly the problem with Gaiman’s stories: the surface coolness and wow factor distracts us from the profound emptiness underneath, and we can get suckered into staring into the abyss for so long that we risk throwing ourselves in.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

This is not a kids’ movie in the slightest. However, parents might learn something about how not to treat their kids, and the movie might encourage them to pay attention to what their kids are getting into while they aren’t around. But nobody needs to watch this dark, depressing movie in order to learn what few morals it has to offer. How “Coraline” got the child-friendly rating of PG, I do not know.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Toward the end of the movie, there was, what I think to a young child, a really terrifying scene where the girl is caught in a giant web, and the sinister “other mother” is coming toward her. What is all this doing to the sweet innocent minds of our children? Must we corrupt them before they can even think and reason on their own? I really agree with the reviewer of this film. It put the traditional family in a very negative light and uplifted selfishness and self-fulfillment.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Neil Gaiman’s life is a sad tale of adultery, divorce and lies. He now dates a bisexual woman 15 years his junior who sings about being raped. If anyone needs prayer, it is this man who is absolutely lost. I cannot recommend his books or his films. Neil Gaiman walks in darkness.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

Also be warned that if your kids follow Neil Gaiman, they will discover a bizarre alternative life style this “children’s author” indulges in that is quite disturbing. After divorcing his wife, Neil Gaiman became involved with a woman 20 years his junior, Amanda Palmer. Together they published a book that is a series of snuff/mutilation photographs of the young woman covered in blood staging her own death. The two launched a public campaign about their “relationship” and participated in an auction where the young woman performed fellatio on a phallic object which was then auctioned off. Amanda Palmer has also posted a series of naked photos of herself on Twitter and the Web covered in grotesque writing and slurs.

Neil Gaiman even declared that his favorite photo was of her bruised and bound body. What is the message for young women here? Neil Gaiman is morally bankrupt, and it shows in his story and in his life.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Many things about this movie made my mouth drop, like when Coraline stated, “Moms don’t eat daughters.” Or, when all the dogs at the show were staring at the nude old lady with the triple D sized chest? Or, when the other old lady was fitting one of her healthy dogs for his death outfit? Sick. This whole movie was disturbing.

Coraline is a rude, cold, angry, disrespectful girl living in a dark world where she’s neglected and ignored by her parents (especially her mother) and thus stumbles upon what she hopes to be a “better” world. Turns out it’s not. Perhaps the moral of “Coraline” should be, “One should be content living in a creepy, bug infested home where parents neglect you and fed you slim, because, life could always get worse.”

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

To relay from the mouth of my 10 year old child, “Mom, why do they put those things in movies for us?” He went on to tell me, “Mom, that just is not right.” If a 10 year old boy can see the error in this movie, certainly we can all see these things that would displease Christ.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: ½

The first scene of the movie shows Coraline using a divining rod, later she’d have her tea-leaves read by Miss Forcible and Miss Spink. Satanic/Demonic symbols throughout. I can’t believe Christian reviewers haven’t jumped on this… I’m very open to what I show my kids (6, 5, and 3), we recently took them to the Edward Gorey exhibit (The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Tuning Fork, etc) which is twisted in it’s own right, but has some artistic value. We’ll watch PG-13 movies on occasion. Recently, we all loved “Igor,” a very good movie.

If the moral of the story is not getting everything you want, doesn’t she get everything she want’s in the end?

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2

“Edginess” in a movie isn’t always bad. A Christian film can be “edgy” by portraying a drug dealer who finds Christ and be a terrific movie. “Darkness” however in a film can be objective and controversial. And seeing how so many reviewers had mixed feelings about the film, I was starting to wonder if it was really worth watching a film that no one can decide whether it’s good or bad. See all »

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

The reviewer was a bit too focused on the film’s negatives, I believe, and he didn’t give enough insight into Coraline’s character progression from the beginning of the movie towards the end. She loves her parents—she shows them more affection and spends more time with them at the end. The movie does show a broken family and relationship lifestyle; who can make straight what God has made crooked? See all »

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Second, why take your little kids under age 7 to see this? Obviously, you should have guessed they would get scared. The commercial was very dark and spooky, and you should have figured it out. I saw several scared kids in the audience when I went to see it, and frankly, I felt sorry for them. Parents, next time, if a commercial looks dark and scary, don’t take your little kids to see it. Go see a G rated movie instead. You won’t have to waste your money!!!

Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 5

“Coraline” is based on a book of the same name by author Neil Gaiman. If you’ve seen the commercials, you probably already know how the story goes. Coraline (Dakota Fanning), a young girl who is utterly disgusted with her boring life and inattentive parents, discovers an alternate reality through a small door in her wall. The world she finds seems tailor-made to suit her needs, but of course, everything is not what it seems. She soon finds herself running for her life from the Other Parents and the world they’ve created for her.See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

1. One of the old ladies was wearing nothing but sequins to barely cover parts of her body, and it was worse than a bikini. And the fact she had an impossibly big chest. And Coraline, I’m afraid, made comments like, “She practically naked!” but she was laughing, clearly amused, like it was a good thing. That disturbed me more than the image of the sequin lady itself. However, it was more idiotically ridiculous than sexual.See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

overall I enjoyed the movie but prefer the book. (the book is a lot creepier)

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

1. The Other Mother is domestic, hence, the film says domesticity: evil. This isn’t right at all. Domesticity is something Coraline’s life lacked but she wanted. The Other Mother uses her cooking to tempt Coraline to stay in the other world. This shows that domesticity is something children crave in their lives. Real evil in the world can warp or use good things to tempt people into doing things that they wouldn’t otherwise. This can be sinning because it seemed right, or running away to live with people with buttons for eyes because their lives seem preferable. See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 3

Then when she made a friend named Wybie, she was extremely rude. I actually thought this movie would get better when she found the secret door, but it just got worse especially when the old woman only had a thong and sequined pasties. It was disgusting. And it was shocking that I heard laughter on that scene. My mom and I shielded our eyes, and Coraline had the mind to laugh and say “She’s practically naked!”. See all »

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1

There is a scene where a woman with a large chest is nearly in nudity. I am a young child who is still growing in Christ, and if children know there’s something wrong… it’s not worth buying. Don’t rent, buy, or even borrow this movie from a friend. Don’t spend the time or money just to fill your innocent, clean, christian mind with atheist thoughts, if you do… you’ll regret it. Don’t believe what the commercials say, they don’t show the bad parts.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2

I didn’t think this movie was completely clean, and I definitely wouldn’t want anyone under around 10 watching it, unless they were highly mature. But, it’s a great movie. I now own it on 2-disc DVD in 3D with the glasses and everything. It is definitely on my Top 10 list.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

The commercial showed it was going to be scary, so you should have used better judgment and resented!!!… Yeah, they probably would have whined and cried and threw a fit on the floor, but better that than them being introduced to evilness!!!… So do yourselves a favor and next time a Henry Selick or Tim Burton movie comes out… Do not take your kids to see it!!!…

Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Anyways, the movie Coraline tells the story of an 11 year old girl named Coraline that moves into the Pink Palace Apartments with her very busy parents. Her parents love her very much, they just have demanding jobs. Coraline is a little snappish and bossy, but that’s how kids are sometimes. She really just feels abandoned and bored, since her parents are always working, and deep down inside has a heart of gold. Also, her relationship with a neighborhood kid named Wybie is certainly not abusive, as the featured reviewer pointed out. He’s just a shy and awkward person, and she’s not that mean to him at all (She even apologizes later).See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

But, religiously, I think it’s okay. *important* I also want to definitely note the complaints of nudity. The mentioned scene where a large breasted woman is only wearing nipple covers and a thong is in fact in the other world, and, if you watch, she unzips her “body” to reveal that it is just a disguise, and underneath she is actually quite small and fully clothed. The same with the other lady. I do understand, however, that at first it’s only natural to assume that is her body. But it isn’t. And I REALLY find it funny that no one writing negative comments has said that part. They just stop on the “nudity” part and don’t give the full picture.

Well, thanks for reading and go see the movie! (It’s great!!!…) **May be offensive to some, I guess.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

But as Coraline comes more and more to this place, she realizes that the world of her dreams is quite frankly the world of anyone’s nightmares. When watching the film, one should be cautious of the mature content, the audience it is primarily speaking to, and heed the Christian message that is demonstrated throughout the plot.

The movie starts off with Coraline moving in to her new home at The Pink Palace, which is an old apartment complex in a secluded, rural area. Right away the audience can see that her relationship with her parents is poor, and the sass and disrespect she gives them is a bad example to young minds. The parents do not care for what Coraline does, and vice versa. Coraline also abuses, both physically and verbally, the character named Wyborne (Wybie), who she has a distinct hatred for. This can also be a negative example for children, who may misconstrue such actions as Coraline only acting independent and confident. See all »

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

Don’t show this to kids. I didn’t watch the entire movie because it was to creepy. We got to the part with the ghost kids, and that was it. I had thought this movie would be cute, because it had buttons on it. I had originally thought buttons were sweet, after watching this, I considered them one step removed from intrinsically evil. Of course, now I’m over most of that. Buttons and stitches don’t bother me, I can say the name Caroline without even a flinch, and I like sewing. But now ten years later, I am STILL scared of this movie. And I’m fifteen. FIFTEEN! It’s been ten entire years since I watched this and I’m still really creeped out by the monster. I’m not scared of buttons or anything like that, but it’s been a decade since I saw it and I’m still disturbed. This movie literally scarred me for years, possibly for life, so take my advice. I warn you, DO NOT SHOW YOUR KIDS. It’ll scar them.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2½

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

She ends up in a world where she gets everything she wants and everything is perfect… almost. This is a classic Good vs Evil scenario and being tempted by the dark side into joining with them. She refuses. She begins to recognize this and tries to escape. As things go a long, everything becomes more evil and twisted as this “perfect world” begins to show its true colors. Coraline realizes she should love her parents for the how they are and that they don’t spoil her with everything. As for the slam against traditionalism making the woman who stays home and cook and all that evil… I just began rolling my eyes at that part.See all »

The film introduces us to a heroine who is spunky and adventurous and hates it when her name is mispronounced. Coraline is the Dorothy of a new “Wizard of Oz” like story. Just when she thinks the world would be a better place she learns that not everything is as good as it seems. The story begins… The content of the film should be considered by parents who want to take the younger kids with them. The other world features a barely dressed busty woman and the Other Mother would give you nightmares.

Being a fan of Neil Gaiman, I loved the film and would recommend it to anyone who wanders what’s a good film to see. The special effects are remarkable and are in your face in 3D.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5