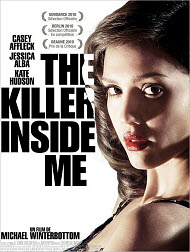

The Killer Inside Me

for disturbing brutal violence, aberrant sexual content and some graphic nudity.

for disturbing brutal violence, aberrant sexual content and some graphic nudity.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Extremely Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Thriller Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 49 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2010 |

| USA Release: |

January 24, 2010 (festival) June 18, 2010 (NYC) DVD: September 28, 2010 |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Casey Affleck (Lou Ford), Kate Hudson (Amy Stanton), Jessica Alba (Joyce Lakeland), Ned Beatty (Chester Conway), Elias Koteas (Joe Rothman), Tom Bower (Sheriff Bob Maples), Simon Baker (Howard Hendricks), Bill Pullman (Billy Boy Walker), See all » |

| Director |

|

Michael Winterbottom |

| Producer |

| Muse Productions, Revolution Films, Hero Entertainment, Indion Entertainment Group, Stone Canyon Entertainment, See all » |

| Distributor |

| IFC Films |

“Nobody sees it coming.”

Only one scene in Michael Winterbottom’s film adaptation of Jim Thompson’s 1952 paperback classic, The Killer Inside Me evokes the sense of the original. Lou Ford (Casey Affleck), the small town Texas sheriff whose polite and dull demeanor masks a boundless lust for ritual humiliation, sadistic sex, and serial murder removes a Bible from the shelf of his late father’s library. Inside the book he finds some pictures that his father had taken of his mother and had hidden years ago. The obscene photographs reveal to Lou not just who his father was, but what he himself was becoming. After Lou looks at the photographs, he burns them. These quiet scenes of discovery, recognition, and efficient disposal capture the psychopath’s nature much more effectively than the violent acts that the movie uses as its focal points. The remorseless murderer cleans up blood as efficiently as he spills it. There is as much precision in Lou’s evil chaos, as there is creepiness in his fine-tuned routines.

I read The Killer Inside Me when I was 12. I shouldn’t have; it’s not a book for children or teenagers, and the movie certainly is not fit for children or even adolescents. Jim Thompson wrote paperback originals in the 1950s and 1960s. The books were sold at bus stops and newsstands for 25 cents a copy (today an original sells for as much as $1000) and were meant to be read once, and thrown away. His works don’t constitute great literature the way Raymond Chandler’s The Last Goodbye and Dasheill Hammett’s The Glass Key arguably do. Thompson’s plots are not strong; that may be why his novels don’t translate well to the screen. Only Sam Peckinpah’s “The Getaway” (1972) with Steve McQueen and Ali McGraw, and Stephen Frears’ “The Grifters” (1990) with Angelica Huston, John Cusack and Annette Bening proved to be successful film adaptations of Thompson works.

An earlier version of “The Killer Inside Me” made in the 1970s and starring Stacy Keach is even worse than the new version. Thompson’s stories have all the right elements: vivid local color (the film does go to great lengths to reproduce that color and largely succeeds), a strong, tough, familiar American voice (very different from the mansion and parlor voices of the Agatha Christie British school of crime fiction), a folksy narrative rhythm, and characters who exist on society’s fringes, outsiders in search of a heaven on Earth who invariably wind up with the opposite. For them, payday usually turns out to be judgment day. Those elements sometimes shine through on the screen. In Winterbottom’s film, they show up, but they don’t take hold.

Our world makes a lot of promises, but, even when those Earthly promises are fulfilled, they tend to disappoint. They cannot appease a spirit that longs for the promises of another world, a more lasting and fulfilling one. That truth is at the core of Thompson’s work, and at the heart of the great American crime movies. Think of Casper Gutman’s quest for a statue: “I couldn’t be any fonder of you if you were my own son, but… if you lose a son, you can get another… there’s only one Maltese falcon;” or Marion Crane’s search for a new and better life as she escapes a dreary life in Phoenix to pursue something better on the road west, a long trip that necessitates a short stop at a roadside inn called the Bates Motel; or Noah Cross answering Jake Gittes’ question about what more a rich man, who already owns most of Chinatown and a good part of California, could buy when he already has everything: “The future, Mr. Gittes, the future.” All of these doomed characters are looking for heaven.

Granted, it’s a displaced search, but there is something in those characters’ spirit that makes them strive for more, for something outside of themselves. It is that perverted image of heaven that drives the stories behind the best crime fiction, and the best crime movies.

No one has gotten into the mind of the criminal the way Jim Thompson has. His crime stories are often told in the first person from the point of view of the psychopath. We may not ever understand the nature of such a character, but only Thompson lets us walk in the fiend’s shoes for awhile, lets us get close to him, and lets us vicariously become the unfortunate victim who gets taken in by the kindness of a stranger before he pulls the rug out from under us.

Lou Ford is the deputy sheriff in Central City, Texas. He is 29 years old. Nothing remarkable happens in the town; from all appearances, it is a comfortable and modestly prosperous place. Lou does not even carry a gun. He looks gentle, almost slow, and he behaves politely: “We always say yes, sir or no, sir.”

He is a rotten tree who tries to bear good fruit. He sprinkles his sparse speech with seemingly harmless throw-aways: “If you don’t hurt them, they won’t hurt you,” “a man doesn’t get any more out of life than what he puts into it,” “haste makes waste,” but he says them in ways that taunt and throw his listener off guard. In the novel, Lou says that “striking at people that way is almost as good as the other way, the real way.” His verbal teases are warm up acts for meaner things to come.

Lou has a girlfriend, Amy (Kate Hudson), but he becomes involved in a sadomasochistic affair with the town prostitute, Joyce (Jessica Alba ). He slaps Joyce with his hands and with his belt. He attributes his penchant for beating her to childhood episodes in which his mother encouraged him to hit her the way his father did. When Lou was a boy, he molested a young girl, but allowed his older brother, Mike, to take the rap and go to prison for the crime. After his release, Mike was killed on a construction site. The site owner, Chester Conway ( Ned Beatty), may or may not have been involved in Mike’s death. This is where the plot gets fuzzy and makes little sense.

Lou’s predilection for covering up past crimes would have made Mike’s death a convenience for him and not a reason for revenge, but in what is played out as a vengeful act, Lou kills both Conway’s son, Elmer (Jay R. Ferguson) and Joyce, and sets the victims up as the killers. The double murder leads Lou to commit more killings in order to cover up the original ones.

Lou’s crimes are hard to watch on the screen. He punches his fiancé so hard that he has to pull away extra hard to extract his fist from the cavity he has made in her abdomen. She can barely move as she tries to crawl toward him on Lou’s shiny kitchen floor. Her shaking hand reaches for his boot as he stands above her, but he moves the boot away. As she lay dying on the linoleum, he sits at the kitchen table and tries to read a newspaper.

The rest of the killings are just as gruesome. Throughout, Lou maintains a cool detached façade. No one can break him, not even the town’s relentless district attorney (Simon Baker). In between murders, Lou listens to Shubert and Donizetti, reads Freud, and works out calculus problems. We only see cracks at the edges.

The biggest crack comes when he begins to lose his connection to the world around him. Neighbors, co-workers, and even lovers start to move away. Once that attachment disappears, he starts losing what is left of the world he crafted and the self he made up. I enjoyed that part of the movie. It was subtle, but well focused, and what a pleasure it was to watch a movie in which the small town people were not backward, impenetrable or just plain daft. The residents of Central City are depicted as having an innate and well-honed sense of what is good and what is bad, what needs protecting and what should be kept at a distance.

Casey Affleck plays Lou Ford. I have mixed feelings about the performance. Physically, he’s right. He’s small and lean; he tries hard to fit into the sheriff’s clothes and the big cowboy hat, but everything he wears seems several sizes too big. He has a smile that is weak, but his eyes can be piercing, even when there’s nothing behind them. There is a light rasp to his voice, a kind of Chihuahua growl. His grin is comforting when he talks reassuringly to a waitress only moments before it goes wide and bare as he leaves the diner, steps onto the sidewalk, and puts a cigar out in a panhandler’s hand.

The two women in the movie are not well written. They were not well drawn in the book either, but at least in the novel you understood that there are fundamental differences between a schoolteacher and a prostitute. In the film, the two roles seem interchangeable. The performances range from empty (Jessica Alba ) to distracted (Kate Hudson). In fairness, both actresses are not given much to do except act out repetitive and ultimately boring sex scenes and to submit themselves to violent abuse. Too much time is devoted to graphic sex and violence, and not enough time to what might lie behind the women’s isolation and heartbreak, something that would have given some insight into their need to love and be loved by as empty a man as Lou Ford.

The movie looks splendid. The set and costume designs, even the title sequence, have recreated a picture-book 1950s palate. The background is a feast for the eyes, but the movie is a lot like its major character—well groomed on the surface, but lacking underneath. What’s left shows signs of mold and decay. It’s more a spawn than an adaptation. Jim Thompson and the noir tradition deserve better.

Violence: Extreme / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.