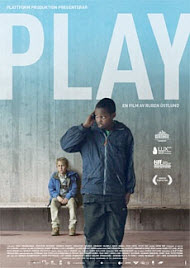

Play

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Drama Pseudo-Documentary |

| Length: | 1 hr. 53 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2011 |

| USA Release: |

May 15, 2011 (Cannes Film Festival) October 15, 2011 (New York Film Festival) |

Are we living in a moral Stone Age? Answer

selfishness

materialistic / materialism

the negative effects of political correctness

How important is it to be “Politically Correct”? Answer

THE NEW TOLERANCE—It’s politically correct, but does it hold danger for followers of Christ? Is love the same thing as tolerance? Answer

failure to communicate

crimes committed by kids

artful dodgers

lack of parental guidance

danger of having no role models and no goals

people who have lost their understanding of what it truly means to be free

Sometimes defending a vague and ever-changing ideal such as multiculturalism can get in the way of our recognizing what is true and in proclaiming the truth when we know it.

cynicism that is prideful and cold hearted—“the cynic knows the price of everything and the value of nothing”

assimilating immigrants into the larger community

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Yannick Diakité Kevin Vaz Abdiaziz Hilowle Anas Abdirahman Nana Manu Sebastian Hegmar John Ortiz Sebastian Blyckert |

| Director |

|

Ruben Östlund |

| Producer |

|

Coproduction Office Film i Väst See all » |

| Distributor |

| Coproduction Office |

I cannot say that I enjoyed “Play,” a new film from Swedish director Ruben Ostlund. I was challenged by it, and disturbed, even irritated by it. It lacks a simple narrative line, so it is not easy to figure out what is unfolding before your eyes, even if you are watching closely. The director maintains a distance between the viewer and the action. The camera stands still and far away for long periods of time, and even after the action has taken place, it’s not easy to put the pieces together and figure out what really occurred.

The experience was exhausting and at times frustrating and annoying, but the challenge was worth it. This is one of the best films I have seen in some time. It premiered at the New York Film Festival, and one of the pleasures of being in the audience was watching; actually it was more like sensing and feeling; the rest of the audience squirm in their seats. I squirmed too. “Play” was probably the least attended of all the films that debuted at the festival.

No boundaries were pushed at this year’s festival, certainly not from the directors who drew the biggest crowds: Martin Scorsese, Lars Von Trier and Roman Polanski. “Play”, on the other hand, did not just push liberal boundaries; it shoved them around and, by the time the film is over, gave them a black eye.

The movie opens in a Swedish shopping mall, a modern day temple to consumerism. Inside the mall complex, material things abound, one on top of the other. The people who move about in the mall are tiny and insignificant; they look like insects in an ant farm. The action unfolds slowly and not all that clearly. I kept wishing for a little more exposition or a close up, so I could get more involved. My impatience was getting the better of me, but I needn’t have worried; I would soon be very involved.

It seems as though several disjointed stories are taking place at once, a kind of mishmash in which we might think that everything will in someway be connected; a kind of “Crash” or “Babel” tale about how what goes around comes around. That is not the case, at all. There is just one story, and it is a gripping one about people who are from different walks of life. They meet, but they never come together. A failure to communicate doesn’t hamper the story; it drives it, and it is that failure that brings the characters and the society in which they live crashing down.

Three Swedish preteen boys—two Caucasians and one Asian—are in the shopping mall when they are approached by four African immigrant boys who toy with them by asking to see one of the boys’ cell phones. The easy going and naïve boy hands him the phone. The immigrant boys, accomplished petty thieves and swindlers, a band of artful dodgers , but without the paternal guidance of an adult Fagin to channel their budding criminality, accuse the Swedish boys of having stolen the phone and set up a sting into which the gullible Swedish boys quickly fall.

The immigrants take them on a long, eerie, increasingly dangerous hike from the mall to the outskirts of town on cable cars and buses, across playgrounds and fields, under highway bypasses, and into the woods. The thieves are deft at baiting and switching, using a soft touch followed by an iron hand, effortlessly morphing from deal-making gentlemen into savage barbarians, with little warning in between. It’s not long before the Swedish boys, who are not nearly as fast on their feet, find themselves in a hell they walked into but cannot escape from. Their only response is to keep walking deeper into the morass.

“Play” is a twenty first century “Lord of the Flies,” but this tale does not take place on a remote island far away from the guiding forces of adult civilization. This nightmare unfolds in the middle of civilization, in, of all places, Sweden, that most sophisticated and cozy of modern societies, in full view of the adult world. Many of the adults watch the barbarity play out right in front of them. They do nothing to stop it. You can see the fear and the hesitation in their faces. They are the comfortable and the secure, the men who believe themselves to be free until their freedom asks something of them. They feel powerless to move because, in their very limited world, they view their own judgment and authority as suspect. They cannot bring themselves to defend the civil order or even themselves because they no longer understand the concept of civil order, authority or even freedom.

They have been taught that order and authority are code words for censorship and oppression, and should therefore be disdained. So what’s to be done when order breaks down and authority cannot speak? Who will defend society’s most vulnerable? The last defense, and the weakest one, is to believe that the barbarians at the gate are not, in fact, barbarians. It is the few who warn against the invaders who are the real barbarians; they are the intolerant, the judgmental, the prejudiced. And since no one wants to be counted among those, it is best not to say or to do anything.

Conformity to such popular prejudice, or what we call political correctness, ties the hands of both the children and the adults in the story. It is sad to see adults unhappy, but it is devastating to see children who have no joy in them. A child’s hands should be raised in wonder, not tied behind his back.

“Play” is about people who have lost their understanding of what it is to be free. Left to their own devices, they are rudderless and have no idea where to go. Their point of view has been narrowed by a culture that does not defend truth or even explore it. Into the void where that encounter with truth once lay comes an array of smaller, but more palatable, things: materialism, sentimentality, relativism, and, specifically in this instance, tolerance and multiculturalism. The gate opens and the barbarians enter, without a fight.

What we are watching on screen is not a far-fetched fable. We see the effects of political correctness all around us. Often we cannot open our eyes enough to even see it. An Army major murders 13 people on a military base, after he had condemned his country and proclaimed himself a jihadist for several years. During those years the major was promoted several times. In a major city, a bomb almost explodes in a densely populated tourist area. The philosophy behind the bombing turns out to be something we are all familiar with and that we all suspected. Nonetheless, the mayor of that city claims that the bombing attempt could have been the act of someone unhappy with a government policy concerning health care. Sometimes defending a vague and ever-changing ideal such as multiculturalism can get in the way of our recognizing what is true and in proclaiming the truth when we know it.

Racial differences are obvious in the movie, but they are rarely spoken. I can only remember one remark, made by one of the immigrant boys, about race. The immigrant boys evoke sympathy, at the same time they create an atmosphere of dread. There is a terrific scene in a mall shoe store in which the camera focuses not on the four boys creating a commotion but on the customers pretending to go on about their business and not even see the boys as they create more and more havoc. The director leaves them out of the frame, but the ball they kick around the store keeps popping into the frame as they shout and holler louder and louder and louder.

I was as unsettled as the store customers. I’ve found myself in the same situation enough times, on a street or on a subway platform, and I’ve been just as paralyzed, not only in my ability to act, but in my perception of what was happening. Is the danger real, or am I just conditioned to think it is real? What conditions me to think that way? Am I wrong to think that way? While I’m busy sorting this stuff out, someone, perhaps me, might get pushed onto the subway tracks.

The child actors do a spectacular job of bringing their characters to life. All are unknowns, and their ensemble work is a marvel. What is particularly refreshing is that these children act the way actual children do, and not in the manner of the smart-allecky, eye rolling, infinitely smarter than their parents and all other adults children whom we see in so many movies and in every television sit-com. Real kids have a long way to go before they become not just smart, but wise. This film shows how difficult the process of gaining understanding can be.

The children in the movie have no role models and no goals. Christ taught us to seek first His kingdom and its righteousness, and all else will be added. When materialism and self come before God and fellow man, the game sums up to zero.

The adults in the story fare no better than the children. The concept of ancestry and reverence for those who came before us is questioned. A group of Native Americans in ersatz native dress perform songs and dances in the street, but, on their break, they eat lunch at McDonalds®. Police appear only toward the end of the film, not as saviors, but as bullies just as menacing, though in a technocratic way, as the immigrant youths who set upon the boys in the first place. They are our modern day Pharisees who know well the letter of the law, but have no understanding of its heart.

A harrowing sequence shows some grown-ups who try to retrieve a stolen phone from one of the African youths. The phone, that burdensome possession that none of us can live without, is a symbol of how we have advanced in our communication abilities, but how we have declined in our communication skills. The materialism and relativism that plagues the children and impedes their growth has given way to a disease in the adult that is even more malignant: a cynicism that is prideful and cold-hearted. The cynic does not see, because he does not want to. Oscar Wilde defined cynicism perfectly when he said that “the cynic knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

The adults prey upon the youth, fight with him (the young boy is more than able to hold his own), and argue with some bystanders who object to the men’s treatment of the boy, but who do nothing to intervene during the skirmish. Neither comes to an agreement, because each adult feels superior to the other and is unwilling to listen. Even when the phone is taken, no one is sure who actually owned it in the first place. No justice is achieved, and nothing is solved. The divide only gets bigger.

The plight of the immigrants, and of the society in which they live with other residents, is not resolved. The film does not answer any questions, but it raises many. The immigrants are not in any way assimilated into the larger community. The rest of society goes on, and it goes on ignoring the elements in that society that prove too uncomfortable.

The “Music Man” style ending feels like cold water on the face, but it’s funny, too. It’s not the people on the screen who are fooled for our amusement; it’s we in the audience who get stung. We put our faith in what we hope will be a satisfying ending, the way the boys handed over that phone hoping for the best. And we get just what the boys got—taken.

As unpleasant as the ride may have been at times, I would not have missed it for anything. “Play” is a daring work, and a superb achievement.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

Are we living in a moral Stone Age? Answer

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.