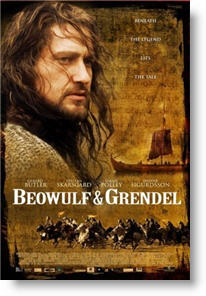

Beowulf and Grendel

for violence, language and some sexuality.

for violence, language and some sexuality.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Extremely Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Action Adventure Fantasy |

| Length: | 1 hr. 43 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2005 |

| USA Release: |

June 15, 2006 |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Gerard Butler, Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson, Stellan Skarsgård, Sarah Polley, Eddie Marsan, Tony Curran, Martin Delaney, Rory McCann, Ronan Vibert, Hringur Ingvarsson, Spencer Wilding, Gunnar Eyjólfsson, Philip Whitchurch, Mark Lewis, Elva Ósk Ólafsdóttir, Ólafur Darri Ólafsson, Steinunn Ólína Þorsteinsdóttir, Gísli Örn Garðarsson, Gunnar Hansson |

| Director |

|

Sturla Gunnarsson |

| Producer |

| Andrew Rai Berzins, Michael Cowan, Friðrik Þór Friðriksson, Sturla Gunnarsson, Douglas Hansen, Peter James, Eric Jordan, Anna María Karlsdóttir, Alex Marshall, Jason Piette, James Simpson, Paul Stephens, James D. Stern, Mark Winemaker |

| Distributor |

| Union Station Media, Truly Indie |

“The Hero. The Monster. The Myth.”

“Over the misty moor

From the dark and dripping caves of his grim lair,

Grendel with fierce ravenous stride came stepping

A shadow under the pale moon he moved,

That fiend from hell, foul enemy of God”

So approaches the monster Grendel in the Old English Beowulf tale. He’s a “fiend from hell” and a “foul enemy of God.” The author expresses no ambivalence in that passage. God and devil, good and evil, darkness and light are juxtaposed in just five lines without a moral equivalent smokescreen.

This is not the case in the DVD release of “Beowulf and Grendel” (2005), directed by Sturla Gunnarsson and written by Andrew Rai Berzins. Gunnarsson observes in an interview:

“But, seriously, we were looking to get away from that ‘good’ and ‘evil’ paradigm. We needed to get into a more humanistic understanding what heroism really is. Making Grendel, in turn, more human allows us to do that” (http://www.moviefreak.com/features/interviews/sturlagunnarsson.htm).

Unfortunately, to make a monster more human necessitates making people less human. In a formulation which could have been taken directly from a book by interspecies advocate Peter Singer, Berzins includes a scene in which the troll, Grendel, forcibly rapes Selma from behind. Selma doesn’t object to the troll’s “taking” her and later admits to having had relations with unnamed “other things” as well. But when she seduces the hero Beowulf (Gerard Butler), she first slaps him before aggressively mounting him.

As distasteful (or ludicrous) as it is to highlight such matters, it is necessary in order to compare how the film views the two characters which represent antithetical worldviews. The witch is the ethical touchstone of the movie, and she invests Grendel with moral authority even when he kills or rapes. Grendel possesses the moral trump card of our time: he is a Victim. On the other hand, Beowulf has no moral authority, even when he neither kills nor rapes. Instead, he is hectored, slapped, and himself raped by Selma.

There is an obvious pacifist moral here: that violence is always wrong, except when committed by Victims or putative non-victimizers (Selma). There is a separate, but corollary, moral lesson in that there are likewise no heroes. Victims (or non-victimizers) are the only sympathetic characters. The male “heroes” in Beowulf (the king and Beowulf) are weak men dominated by women. The king is a drunkard and crippled by grief and guilt. Beowulf is unsure of the justice of his hunt and is crippled by doubt. The movie argues that their subscription to an ideology of force undermines any presumption of authority on their part.

For instance, Beowulf is not allowed to kill Grendel through his great strength, as in the ancient story. Rather, it is Grendel who makes the choice to effectively kill himself. In other words, the hero does nothing heroic.

Ironically, rather than illustrating a fable, the movie itself becomes a fable for our own troubled time. Berzins’s Grendel is a victim of terrorism and consequently inflicts senseless terror in return. In keeping with the project of rewriting traditional myths into contemporary political morality tales, Berzins turns a Christian parable of redemption into a screed of anti-Christian animus, unatonable guilt, and interspecies love. The message is that there would be no terrorism if the cultural “trolls” of our time were left alone. This is an interesting method of framing an argument and not very flattering to the “trolls” currently performing acts of terror.

In an interview with the Writers Guild of Canada, Berzins “recalls being puzzled by the Christian bent to the Beowulf story.” He states:

“It’s very monotheistic, and the references to Cain are very biblical… So we looked at the story, and it was like, OK, what was this story like before the Christian imperative of good versus evil came into play?” (http://www.wgc.ca/magazine/articles/winter06/Beowulf.html).

At least Berzins recognizes that the imperative of good and evil is one of the foundations of Christian thought. Had he been content to portray a superstitious pagan time, without good and evil, he could have portrayed trolls, witches, and sea hags all happily at play. But Bergins’s political animus comes out in the portrayal of a crazy priest, the only ridiculous character in the movie, who falls to the ground frothing, mid-sermon, in an epileptic seizure.

Meanwhile, Selma the witch is shown to have metaphysical knowledge and can foretell the future. She is the divine medium in the movie, much like Dan Brown’s sacred feminine, possessing Mother Nature’s powers and exuding unbridled sexuality. Likewise, Gunnarsson portrays Beowulf saying a prayer to Odin in a reverent manner. The unambiguous message is that religion is acceptable as long as it is pagan, sexual, and mediated by women or absent gods. The only unacceptable faith in an ideology of universal tolerance is Christianity.

The one positive element in the movie is the cinematography. The wild emptiness of Iceland, void of plant life, trees, and animals, is a powerful metaphor for the moral emptiness of the movie itself. In the end, Beowulf triumphs, but as he and his men sail home, the bard cites the biblical story of Cain when he sings of Grendel’s murders. One of the other men says “Thorkfell’s full of shit. We’re all killers.”

The moral equivalence of such a statement is deplorable, but the inability to distinguish between terrorists and the people who fight them is the kind of sentiment that is universal in Europe and much of the United States. Such a perspective doesn’t see a difference between a people defending itself with violence against a people initiating violence. Today’s Grendels are the terrorists whose atrocities transcend the fictional evil of the Grendel monster. Regrettably, too many powerful elements in our society express sympathy for the monsters of our time. For the writer and director, the Bible’s distinction between good and evil is a fable which they re-write to reflect their own inverted reality in which people don’t kill; guns do. Such an ideology perversely invests weapons with the agency it denies to people and seeks to ban the weapons rather than punish the behavior.

Berzins and Gunnarsson somehow miss the implicit argument that their point of view makes: a people who do not believe in good can do no good. Likewise, a people who do not believe in evil will be unable to recognize evil when it breaks down their doors in the middle of the night to devour them.

In portraying trolls as wronged and heroes as wronging; witches as good and priests as fools; men as impotent and women as powerful; Norse mythology as noble and Christian religion as ridiculous, Berzins and Gunnarsson paradoxically reveal the deeply biased nature of their own worldview. A film in which the Christian archetypes of good and evil are absent, while sexual appeasement and cultural surrender reflect desirable modes of response perfectly, summarizes the intellectual vacancy of postmodernism.

Postmodern productions are brave in mocking Jesus, but they are afraid to publish Mohammed cartoons; they courageously attack Christian pastors in movies, but they fear to speak the name of Theo Van Gogh’s barbaric murderer. Postmodern thought deplores the inequality of women in Western society, but it says nothing of the enslavement of women in Eastern societies. Like an Oliver Stone film, this, too, is a deeply dishonest mode of argument and representation.

In the 1990s, such films as “Priest” (1994), “Seven” (1995), and “Dogma” (1999) reflected the merely slanderous anti-Christian fare of the time. More recent fare such as “King Arthur” (2004), “Kingdom of Heaven” (2005), and “Tristan and Isolde” (2006), by comparison, represent an aesthetic leap forward from the demonization of Christians as a demographic group to a concerted, multi-million dollar program to write them out of history. The former three films simply cast Christian characters as either immoral or murderous, while the latter three, and now “Beowulf…,” rewrite the original Christian tales.

For example, that any educated person can be ignorant of the fact that the first Crusade was launched in 1095 in a belated response to more than 350 years of Muslim conquest of Christian lands is unforgivable. Not until 1492 were the conquering Muslim forces finally cast out of Ferdinand and Isabella’s Spain after 700 years of religious tyranny. Worse, Christian Greece and the Balkan countries were oppressed by Islamic rule until 1825, nearly 1200 years after the first Muslim crusades kicked off. It is facts like these that make “Kingdom of Heaven”, like almost all of Oliver Stone’s movies, so maliciously dishonest.

In addition to those cited above are films such as “Saved!” (2004) and “Jesus Camp” (2006) which mock or distort Christianity. When combined with Kanye West’s Rolling Stone cover as Jesus, and Madonna’s stint on a giant cross in an upcoming NBC special, it is difficult for Christians to believe that their faith isn’t being targeted, given that the religion in the real news is most decidedly not Christian.

Meanwhile, films like “King Arthur,” “Tristan and Isolde,” and now “Beowulf and Grendel” misrepresent Christian texts. Clive Owen’s King Arthur surrenders his Christian faith, Tristan and Isolde never express theirs, and Beowulf looks upon the mad Christian monk and reverently prays to Odin. “Beowulf and Grendel” is one more sad chapter in the history of contemporary culture’s animus against Christianity. The movie’s message is that there is no good and therefore no evil; there are no heroes, only victims; and it is better to appease those trying to kill you rather than try to overcome them. Does anyone doubt that such a worldview is doomed to failure and even extinction?

Violence: Moderate / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Extremely Offensive / 1

The author of this review suggests that the “original” poem that the movie is based upon is Christian. That is not the case. The poem Beowulf has it’s true origins in bards' songs and tales that were passed down orally for generations long before the first Christian missionaries made their way to the North Lands or Scandinavia. The poem was changed when a monk (nobody knows his name for sure) decided to write the songs down in a poem. It was written in the version of Old English that was common at the period before Latin-based languages started to influence the native languages of Northern Europe. Yes, at one time, the language this Web site is now written in used to be quite different than it is now. The monk who wrote the poem added the parts about God (of the Judeo-Christian understanding), the Christian missionary character, the comparison of Grendel to Cain, etc. He adapted the story for his audience much the same way that film makers do with old stories today as the write their screenplays.

So, while I agree that this film isn’t for kids and may be considered offensive to Christians, it actually seems to me to be an attempt to recapture some of the truly original pagan world view of the story. They could have completed the job by leaving out the missionary.

Offensive / 5

“Britain was largely Christian during the Roman occupation. After the withdrawal of the Roman legions in the fifth century, three Germanic tribes invaded Britain: the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. The conversion of these people to Christianity began in 597, with the arrival of St. Augustine of Canterbury. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731) tells the story of the conversion. Before Christianity, there had been no books. Germanic heroic poetry continued to be performed orally in alliterative verse. Christian writers like the Beowulf poet looked back on their pagan ancestors with a mixture of admiration and sympathy.”

Additionally, there are these references:

On kin of Cain was the killing avenged

by sovran God for slaughtered Abel.

and ne’er could the prince4 approach his throne,

— 'twas judgment of God—or have joy in his hall.

Blessed God

out of his mercy this man hath sent

But God is able

this deadly foe from his deeds to turn!

et wisest God,

sacred Lord, on which side soever

doom decree as he deemeth right.'

Twas widely known

that against God’s will the ghostly ravager

him I could not hurl to haunts of darkness;

Finally, the movie is NOT like the poem in the most important detail—the heroic action of Beowulf in which Beowulf rips off Grendel’s arm:

The outlaw dire

took mortal hurt; a mighty wound

showed on his shoulder, and sinews cracked,

and the bone-frame burst. To Beowulf now

the glory was given, and Grendel thence

death-sick his den in the dark moor sought,

noisome abode: he knew too well

that here was the last of life, an end

of his days on Earth. —To all the Danes

by that bloody battle the boon had come.

From ravage had rescued the roving stranger

Hrothgar’s hall; the hardy and wise one

had purged it anew. His night-work pleased him,

his deed and its honor. To Eastern Danes

had the valiant Geat his vaunt made good,

all their sorrow and ills assuaged,

their bale of battle borne so long,

and all the dole they erst endured

pain a-plenty. — 'Twas proof of this,

when the hardy-in-fight a hand laid down,

arm and shoulder,—all, indeed,

of Grendel’s gripe, — 'neath the gabled roof

http://etext.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=AnoBeow.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=all

Extremely Offensive / 3

My Ratings: Extremely Offensive / 3