Atonement

for disturbing war images, language and some sexuality.

for disturbing war images, language and some sexuality.

Reviewed by: Ben Tabberer

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Drama Adaptation |

| Length: | 2 hr. 10 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2007 |

| USA Release: |

December 7, 2007 (limited); UK: 7 September 2007 |

What is “atonement” in the Bible?

Sexual Abuse of Children—Go

I think I was sexually abused, but I’m not sure. What is sexual abuse, and what can I do to stop the trauma I am facing now? Answer

Does God feel our pain? Answer

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

What about the issue of suffering? Doesn’t this prove that there is no God and that we are on our own? Answer

What kind of world would you create? Answer

What is true love and how do you know when you have found it? Answer

How can I deal with temptations? Answer

Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

How far is too far? What are the guidelines for dating relationships? Answer

What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

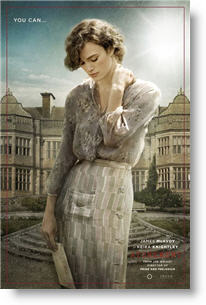

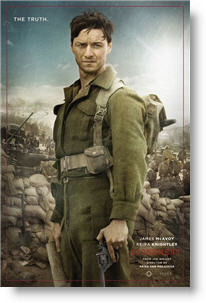

Keira Knightley “Pirates of the Caribbean,” “Pride and Prejudice” James McAvoy “The Last King of Scotland,” “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” “Becoming Jane” Romola Garai, Saoirse Ronan, Brenda Blethyn, Vanessa Redgrave, Juno Temple |

| Director |

|

Joe Wright |

| Producer |

| Liza Chasin, Debra Hayward, Richard Eyre |

| Distributor |

“Joined by love. Separated by fear. Redeemed by hope.”

A T O N E M E N T. The letters comprising the word appear one after the other on the big screen as if typed on a typewriter, and are thus imprinted on the minds of the audience as confirmation of both the overarching theme and literary nature of the story that’s about to unfold. Opening in pre-war England, 1935, on the hottest day of that year, the story begins with Briony (here played by Saoirse Ronan), a 13 year old girl, sat at the typewriter in her affluent family’s country mansion, having just finished a play entitled, “The Trials of Arabella.” The play, we soon learn, is intended to be performed by her and her young cousins that evening for the enjoyment of her family and honored guests. Events that day take an unexpected twist when Briony sees her sister, Cecilia (Keira Knightley) strip off her clothes and dive into the garden fountain in front of family friend Robbie (James McAvoy).

Cursed with an over-active imagination, Briony misinterprets what she has witnessed (a minor quarrel between Cecilia and Robbie) leading to salacious thoughts and gossip. This is exacerbated when Briony later intercepts an erotic letter written by Robbie, intended for Cecilia’s eyes only; further still when later that evening when she walks in on Cecilia and Robbie in a passionate embrace. With Briony’s confused mind already at fever pitch, the nights drama reaches it’s apex when she discovers her eldest cousin in the aftermath of being raped, as we see her unidentified attacker disappear into the night. In Briony’s mind’s eye their can only be one person guilty of the crime, that is perceived “sex maniac” Robbie. With a false (or rather disingenuous) sense of confidence that this is the case, Briony relays the incident to family and police who accost the accused accordingly.

Five years on and Robbie, we discover, is at war in France, just prior to the Dunkirk evacuation. Granted parole for joining the infantry, yet relegated to private due to his criminal record, Robbie heroically guides members of his company to the evacuation area, amid traumatic scenes of the aftermath of war, where they await departure. Meanwhile, we discover that both Briony and Cecilia have joined the war effort in a more gender specific capacity, as nurses. However, the sisters are miles apart (emotionally, as well as geographically) and nursing in different hospitals tending on wounded soldiers returning from France.

Cecilia seems to be at peace in her new role, which now gives her life a sense of meaning and purpose. Conversely, Briony (now played by Romola Garai) is riddled by guilt and immerses herself stoically in her work as form of self-flagilation. As the war draws to a close, old relationships can be rekindled as Cecilia and Robbie are reunited and form a covert relationship once again. Motivated by strong feelings of guilt and for a need for atonement, Briony goes in search of her Cecilia to come clean about what really happened that fateful night. Upon finding her sister and Robbie living together, and coming clean to the pair, the process of reconciliation can begin… or can it?

While bearing many of the features of a classic period drama, “Atonement” does have some content that could offend Christian audiences as well as sensitive viewers. There is some foul language uttered by certain characters including a few instances of the f-word during the war scenes. The c-word is also displayed in writing in the scene where Briony reads the erotic love-letter. The Lord’s name is also taken in vane on one occasion.

Aside from the bad language, there are also a few highly sexually charged scenes, the foremost being the rape scene. While we only see the aftermath of this, it is nonetheless as unpleasant as one would expect. Secondly, there is a scene where we see Cecilia emerge from a fountain with her under-garment wet and transparent. The other is the scene where Robbie and Cecilia are in the throws of passion in the library, and it is clear that they are in the early stages of intercourse. That said, both of these scenes are tastefully done when compared to how some contemporary film handle such scenes, and there is no real nudity to speak of. There are also some gruesome post-war scenes where soldiers injuries are displayed in a particularly graphic manner, and a disturbing scene where Robbie encounters a massacre of French schoolchildren.

“Atonement” is brimming with relevant spiritual issues, although the treatment raises more questions than answers. Etymologically speaking, the word “atonement” derives from an Anglo-Saxon hybrid of the words “at” and “onement” which rose to prominence in the theological vernacular courtesy of William Tyndale. When Tyndale was writing the English Bible in 1526, he was looking for a word that would convey a more subtle theological nuance that the word “reconciliation” so as to also comprise the ideas of God’s forgiveness and propitiation. Amid this search, the word “atonement” was born and has remained an integral component of theological language and thought. However, although the pervading theme of the movie (and the novel) is ostensibly atonement, whether the director and screenwriter effectively convey the subtle nuances of the term through the story is open to debate (in some ways the story could have more fittingly be called “Reconciliation”). What can be said though is that the theme of atonement is only one amongst many that are explored here. The themes of guilt, shame and anger are also probed in a profound and thought-provoking way. While these themes are dealt with in an intellectually and philosophically satisfying, the supposedly overriding theme of atonement is dealt with in a way that is theologically troubling to those familiar with the biblical concept.

The central protagonist spends the last third of the film attempting to atone for a specific sin. This attempt is essentially made through a process of self-flagilation, which even a casual reading of scripture will show to be doctrinally wrong. Further more the end product of this desire for atonement is to be found in a novel written by the protagonist in which she re-imagines the history of the two lovers whose lives she ruined by giving them a fictitious happy ending. The New Testament makes it abundantly clear that it is Christ who made atonement for us, and that we cannot make atonement for our sins in and of ourselves. However, in the final scene, the protagonist appears to be vindicated by this “final act of kindness.” The concept of atonement is after all a Christian one and the fact that the idea of true atonement is never explored leaves something of a bitter taste in the mouth.

However, theological nit-picking aside, I have nothing but praise for “Atonement.” Make no mistake this is filmmaking par excellence. The cinematography is sumptuous, at times breathtaking; the acting excellent (Knightly and McAvoy have never been better); and the script tight. From what little I managed to read of the book before viewing the film, I found the adaptation to be faithful and evocative of the writing, the lyrical poetry of the book was replaced by the visual poetry on screen and the complex narrative was handled expertly in the editing. The characters were given a complex texture and the patience of the viewer is slowly rewarded as we see the story masterfully unfold. A harsher critic might say that at times some of the dialogue seems a tad anachronistic and the cinematography a little too much like a fragrance commercial, but there’s really very little to fault this film in terms of technical expertise, and we can expect Oscar’s aplenty come next spring. A real triumph of British cinema.

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

The film doesn’t pretend to any religiosity, making the reviewer’s points about the atonement of Jesus rather moot. Briony is attempting to make atonement for her actions by rewriting history as a novel (she is a writer in the movie, and in the book—fiction within fiction). Of course, people do this in real life every day—we all attempt to “rewrite” the un-loving things we say and do toward people; we try to right our wrongs. What is shattering to the viewer of the film and the reader of the book is the ending, and the realization that although we may attempt to make things right, many actions cannot be changed and/or reversed, and we’re usually left living with the events we set into motion. Nothing religious about it, but definitely much about real life.

(Note: The secret note given to Cecelia from Robbie was not intended for her to see; although he wrote it, a scene depicts him writing numerous notes—including the ribald one—before he settles on the more formal note. Unfortunately for him, he doesn’t throw out all of the rejects, and accidentally sends along the wrong one. He realizes his mistake after sending it on.)

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

It did have high emotional content, though (unlike most movies’ cheap sex scenes). It represented two childhood friends who for months (or years?) repressed their feelings for each other, so you have all this sexual tension suddenly being released. Overall, everything is done very respectfully. You go on to see how the couple is betrayed, and you see the very heavy impact of WW II. Due to the superb filmmaking quality, I highly recommend this film to everyone—late teens/college age and older.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Like many in our society today, saying you are sorry does nothing to atone for past sins. It might make you feel better, but it has no effect on the people hurt. The same point may be made by States and Institutions apologizing for slavery, but saying you are sorry today only makes us feel better and does nothing to help those who endured the cruelty of slavery but are now long dead. Briony, even in her old age never realizes how evil of a person she is. But she is sorry.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Overall, I found this movie to be quite tastefully done. Some of the war scenes were a bit much for my sensibilities, but this is the truth of war. Without these scenes, I don’t think it would have had the same impact. Briony, I believe, taught the lesson of self-forgiveness. How many times have I blamed myself for something I cannot change? Briony, I believe, wanted to, but it was too late and, for that, I can understand why she would blame herself for the rest of her life. She never truly found atonement for what she did, but she tried to make up for her actions in the best way she knew how. This was a beautiful movie that I would highly recommend to anyone old enough to see it!

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Keeping in mind that many Christian viewers may be opposed to the sexuality between two unmarried people I would argue that the film has merit despite those scenes. We all know that people fall in love and are sexually attracted to one another outside of marriage and many people act on it. The sexual scenes set up the storyline showing two young people from different class structures who are drawn to one another despite their social circumstances. Nothing can stand in the way of their love. These two would not be “allowed” to marry in their situations and I thought the film did a terrific job of showing the angst created by such a situation.

Christians need to be realistic about the fact that having films where everyone is in a situation which allows for wholesome dating that results in marriage and a happy-ever-after ending is not depicting an accurate view of the world in which we live. I am happy to live in a country where art can depict reality.

The film’s treatment of war and its descruction on relationships is phenomenal.

This movie blew me away. It was one of those rare examples of the movie being better than the book.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

On a moral level, this film does not strive to preach, but to be realistic, which should be its major goal anyway. And it succeeds at it. It shows the harm that jealousy and lying bring. And though Christians may complain about the sexual content, hopefully they can see that there are consequences to the sex scene that play throughout the entire film. You can see these lessons without the movie having to spell them out for you.

All in all, an amazing film, the best of 2007. And one of the most heartbreaking movies I have ever seen.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

I basically tried to guess the plot and what was to occur so that I would not fall asleep. I was expecting less sex, and some war images that were going to make it a rated R. It was okay. These were unsaved people, so I expected them to act in that manner, so I wasn’t expecting some noble characters. It was just a love story between two worldly people with a twist, and a some sexual related material that could’ve easily been done different, but was in there for the worldly audience to get a kick out of. This movie could have easily been made to be a PG or PG-13.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

It was disturbing to see such a young girl coming face to face with such horrible sexual content (the letter with the perverted word for a woman’s private place—flashed on the screen several times, walking in on her sister having heavy sex in the library, stumbling upon her cousin being raped). She was a normal young, bright, girl who’s innocence was being taken from her around every corner (corners she was too curious and naive to avoid). Although she was definitely not without sin, a girl of this age is normally curious and it was sad that there was no one there to guide her through such shocking events.

Secondly, I think that the director failed to show a deep, wonderful, lasting, as well as passionate, relationship between Celia and Robby. This would have made the other parts of the movie mean so much more to me personally; especially when Briny spends so much of her life trying to make up for the actions that led to the ruin of their relationship and life together. (By the way, to say that Robby and Celia would have had this amazing life togehter if Briny would have just told the truth, is a really huge assumption to me.)

Although they seemed to love each other, what was viewed between Celia and Robby was mostly a powerful, lustful attraction-the rest of their relationship was pretty much “made up” by Briny. I would be concerned about any young girls/guys seeing this movie, particularly the sex scene in the library. After beginning intercourse, Celia and Robby declare their love for each other in the heat of a extremely passionate sexual encounter. Obviously this film doesn’t show the value of waiting to have sex until after marriage, and seems to say that this is the ultimate expression of passionate love. Truth is a theme in the movie, but the truth is, we were never meant to carry the weight of the sin in our lives, and also that our sins do not have to follow us all our lives.

There’s only ONE who can carry the weight of sin. One positive about this movie is that it does show sad consequences as the result of sin. Even the divorce of Briny’s cousin’s parents is shown to have a very negative affect on their children. I really didn’t feel that what Briny did was SO horrible. It seemed very foolish to put the weight of Robby’s innocence on a immature, confused child. I put more blame on the adults in the movie surrounding her life.

I felt so sad for Briny that she didn’t have a savior (or even an attentive parent) to take all her guilt and shame to. Earlier in the movie, it would have been wonderful if Briny’s mother would have questioned her a little more and helped her through her feelings, all she had seen and perhaps the truth of what happened to her cousin would have been discovered.

So much of what happened seemed tragic and terribly unnecessary. Because of what Christ did for us there is victory, forgiveness and redemption. This movie seems to try to make Briny’s fabrications, torture of her guilt, and attempts to redeem herself somehow beautiful. I call it tragic. As I make decisions about the movies coming out of Hollywood, I have to keep in mind that beautiful cinematography and fine acting aren’t enough to “atone” for disturbing themes/images, sexual content, and unsatisfying endings. By the way, if you want to see a great movie about a kid who tells the truth with great acting and cinematography, then see “The Winslow Boy” with your family (junior high age and up)-it even has a love story. You’ll go away happy and satisfied instead of sad.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 2½

The beginning was good but then right when he wrote that letter to her, which I know wasn’t intended for her or her sister’s eyes, I could not believe what I was reading. There was no reason for the writers to use that word to describe a woman’s private or even to describe his feelings about her or what he would like to do with her.

The fountain scene didn’t bother me too much though but again she didn’t need to get down just into her slip like underwear and dunk in the water to get the broken piece. She could have easily just reached in and got it.

The sex scene in the library wasn’t as vulgar as others are but they were not married and the industry is still promoting premarital sex. The rape scene was not graphic but of course very disturbing.

Not to mention the f-word that one soldier used non-stop in one scene. I just don’t see the point in using that word to make yourself clear of how you feel.

I did feel that it dragged on a little bit. I even catched myself falling asleep and also on some parts it would jump and I would have to ask questions as to when that was (in parts of the movie it says 4 years later, 6 months before, etc.).

I really wanted to like this movie and give it a good rating but morally I just can’t do it because of the things mentioned above. It is still disturbing to me. Pride and Prejudice was so much better than this movie so if you want to see a well written, well directed and great imagery go see that movie.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

My Ratings: Average / 4½