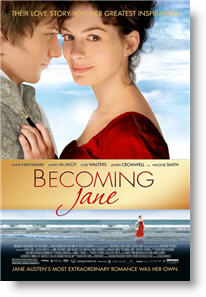

Becoming Jane

for brief nudity and mild language.

for brief nudity and mild language.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults Young-Adults Teens |

| Genre: | Fictional-Biography Romance Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 52 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2007 |

| USA Release: |

August 3, 2007 (limited) August 10, 2007 (wide) |

TRUE LOVE—What is true love and how do you know when you have found it? Answer

For a follower of Christ, what is LOVE—a feeling, an emotion, or an action? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Anne Hathaway (Jane Austen) James McAvoy Julie Walters James Cromwell Helen McCrory Maggie Smith See all » |

| Director |

|

Julian Jarrold — “Kinky Boots” (2005), “Crime and Punishment” (2002 TV), “Great Expectations” (1999 TV) |

| Producer |

| Jeff Abberley, Robert Bernstein, Jolia Blackman, See all » |

| Distributor |

“Between sense and sensibility and pride and prejudice was a life worth writing about.”

Review updated Aug. 14, 2007

The movie “Becoming Jane” is a double-edged sword. For those who haven’t read Austen’s novels and are unfamiliar with both her and her characters, it is an attractive but slow-paced period piece whose energy derives from James MacAvoy’s engaging performance as Tom Lefroy. Anne Hathaway does a serviceable job in a low-key role. In part, she is convincing because she is so beautiful, but because she is so beautiful is also why she is not convincing. Jane Austen was a notoriously plain-looking person. The choice of Hathaway obscures the issue that she had neither fortune nor beauty, two reasons a man would marry a woman. A more convincing Jane would have been Anna Maxwell Martin who played her sister Cassandra.

The premise of the movie is that there exists a split opinion in society about marriage that has one side believing in a common sense solution that “money is absolutely indispensable” to life (Mrs. Austen), while the other half of society suggests that a “small fortune will not buy” love (Jane). During the course of the movie people of “sense” (who are prudent and practical) are contrasted with people who are “sensible” (emotional and romantic). These terms also comprise the title of Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility in which Eleanor represents the sister with sense and Maryann represents the sister with sensibility. The essential question put by Jane’s cousin in response to her statement that money can’t buy her love is: “What will buy you?”

As if in answer to the question, the scene shifts to Tom Lefroy fighting barechested for money. The implication is obvious in retrospect: what will buy Jane’s love is passion. What follows is a montage which, presumably, is supposed to demonstrate that Tom is a wild child whose zest for living, so to speak, spills over “the boundaries of propriety” (a phrase Jane struggles with in the movie). He whores (there is no better verb for his actions), he drinks, he gambles, he lies. He is in every way like Wickham (“Pride and Prejudice”), or like Henry Crawford (“Mansfield Park”), or like Willoughby (“Sense and Sensibility”)… all likable rogues without scruple who try (and do) seduce women, ruin their reputations, and cause them to be ostracized from society, from their circle of friends, and even from their families. These were wicked men which our present time interprets as “romantics” with no understanding of the catastrophic harm they did to young women. It is remarkable that the filmmakers offer Lefroy as Austen’s lover since he is the very type of character that Austen despised and portrayed as a villain in her novels. The portrayal of Lefroy in the movie has more to do with the writer’s prejudices than with reality, a common problem in Hollywood.

Austen describes the real Tom Lefroy in a letter to Cassandra (1/9/1796):

“You scold me so much in the nice long letter which I have this moment received from you, that I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved. Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together. I can expose myself however, only once more, because he leaves the country soon after next Friday, on which day we are to have a dance at Ashe after all. He is a very gentlemanlike, good-looking, pleasant young man, I assure you. But as to our having ever met, except at the three last balls, I cannot say much; for he is so excessively laughed at about me at Ashe, that he is ashamed of coming to Steventon, and ran away when we called on Mrs. Lefroy a few days ago.”

But the shrinking violet that ran away at Austen’s arrival is not the Lefroy of the movie. The model for Lefroy’s character can be found not only in Austen’s Willoughby, but in the Willoughby for whom Austen’s Willoughby is named in Fanny Burney’s novel Evelina. Lefroy’s laughing reference to Vauxhall Gardens is an inside joke known only to scholars since the Gardens were a notorious place where young men went to meet prostitutes and to seduce (or abduct) young gentlewomen. It is this very scenario that Burney portrays in her novel in which Evelina barely escapes being raped by a group of men and molested by Sir Willoughby in Vauxhall. Although the filmmakers don’t intend it to do so, Lefroy’s laughing reference to Vauxhall Gardens shows his character’s moral dissipation.

It is appropriate that MacAvoy played Mr. Tumnus, the Faun, in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”, since his talk is filled with sexual double entendres (“horizons must be WIDENED”) and his physical interest in Jane falls short of the verticality of standing before the marriage altar. At one point he laments selling out for money and solicits the commiseration of a prostitute, toasting her as a joint member of the profession which he, as a lawyer, shares.

In the meantime, Jane is being courted by a Mr. Wisely who seems to be a synthesis of Mr. Collins and Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice. He is stilted like Mr. Collins and he is proud like Mr. Darcy. After he remarks that “The good do not always come to good ends,” he concludes with the statement that will famously become the most quoted sentence in all of Austen’s work: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

But the theme of this novel is clearly sense and sensibility which the writers are at pains to redefine, showing people with sense as money grubbers while people who want to have sex are just… “sensible.” At a time when women commonly died in childbirth, when disgraced women were forced to live in abject poverty, and single women were the objects of sexual predators, it seems crass and deeply deceptive of the filmmakers to suggest that Tom Lefroy’s solution, one that is always disastrous in the novels (e.g. Mansfield Park), is what Jane Austen would have chosen.

Jane’s decision in the end will seem capricious to romantic viewers but it at least is in keeping with the author’s character. The movie is well-written and an avid reader of the novels will recognize little catch phrases here and there, as well as characters who are offered as models in the fiction, like Lady Catherine de Bourgh (Lady Gresham, played perfectly by Maggie Smith).

For those readers both familiar with and honest about Jane Austen’s life, character, and values, the film constitutes a revisionist history whose title would make more sense as Unbecoming Jane, for we are shown an Austen that exists only in the imagination of the screen writers and one that contradicts the values she portrays in her novels and in her letters to her sister Cassandra.

Morally, it is offensive in that it portrays wickedness as mere mischievousness. When Lefroy defends the immoral novels of Fielding as showing virtue being rewarded and vice being punished, Jane responds “In life, bad characters often thrive; look at yourself.”

The writers also show Jane portraying a fictional visit to Anne Radcliffe, a novelist who Austen satirized in Northanger Abbey. Radcliffe was a Romantic while Austen can best be characterized as a neoclassical writer. In other words, Radcliffe is not a writer that Austen would go to learn literature from, but Radcliffe is a writer that the filmmakers would prefer over Fanny Burney, a Christian, and the person whose novel Cecilia provided the title for Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

Jane Austen is acknowledged as one of the most brilliant writers in English ever. It is therefore ironic to see her fictionalized as the type of silly fool that she loves to skewer in her novels, falling for a foppish player. If it were not anachronistic, I would suggest a clear case of projection on the part of the writers. The movie, like Anne Hathaway, is pretty to look at but it promotes a mistaken romantic conception of “love” (i.e. lust) that is destructive to the understanding of young people. See it if you must; forget it when you can because the movie’s greatest fault is that it ignores Austen’s faith. Had she been a feminist author, that ideological identification would have been the focal point of the film. What is not known even by many Christian readers is that Austen was a devout Christian whose values inform every novel and are particularly emphasized in Mansfield Park.

For readers interested in Jane Austen’s taste in novels, her favorite woman authors were Fanny Burney and Maria Edgeworth (especially Belinda). Fanny Burney is a wonderful author, almost on a par with Austen herself, and overtly Christian in her writings. Her novels cannot be recommended highly enough to serious readers of literature.

Background Information

For an insight into the character of Jane Austen go to this site which is excellent in the material it makes available but questionable in many of its editorial judgments: http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/janelife.html.

What the reader will discover is that Jane Austen and her family were devout Christians, that they had a high sense of honor (the excerpt on reading another’s letter is indicative of the mores of the time), and that she also composed three prayers which, like all written material, were meant to be read aloud in company. Note that secular scholars commonly write things like “It’s interesting that she prays for the correction of ‘faults of temper’ in ‘Thoughts, Words, and Actions,’ given the rather acerbic comments found throughout her letters” as if a person cannot be both “acerbic” and Christian! This is why she writes in her novel Persuasions that “no private correspondence could bear the eye of others,” a principle that such scholars purposely violate in order to depict their own version of Austen rather than the other testified to by her family. The following excerpts give a clear look at Austen’s character and faith:

On the Subject of Evangelicals

[This letter was written to her niece, Fanny, who was in doubt as whether to marry an Evangelical Christian. Most members of the Church of England frowned on members of other churches. Austen’s open-mindedness in this instance is highly unusual.]

“And, as to there being any objection from his goodness, from the danger of his becoming even evangelical, I cannot admit that. I am by no means convinced that we ought not all to be evangelicals, and am at least persuaded that they who are so from reason and feeling must be happiest and safest. Do not be frightened from the connection by your brothers having most wit—wisdom is better than wit, and in the long run will certainly have the laugh on her side; and don’t be frightened by the idea of his acting more strictly up to the precepts of the New Testament than others.”

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/brablt15.html

Winchester Cathedral Plaque

JANE AUSTEN

/blockquote>

known to many by her

writings, endeared to

her family by the

varied charms of her

Character and ennobled

by Christian faith

and piety, was born

at Steventon in the

County of Hants Dec.

XVI MDCCLXXV, and buried

in this Cathedral

July XXIV MDCCCXVII.

“She opened her

mouth with wisdom

and in her tongue is

the law of kindness.”

—Prov. XXXI v. XXVI.

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/janelife.htmlOn the Faith of Her Family

“This day, my dearest Fanny, you have had the melancholy intelligence, and I know you suffer severely, but I likewise know that you will apply to the fountain-head for consolation, and that our merciful God is never deaf to such prayers as you will offer.”

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/brablt17.htmlA Prayer Written by Jane Austen

Give us grace, Almighty Father, so to pray, as to deserve to be heard, to address thee with our Hearts, as with our lips. Thou art every where present, from Thee no secret can be hid. May the knowledge of this, teach us to fix our Thoughts on Thee, with Reverence and Devotion that we pray not in vain.

Look with Mercy on the Sins we have this day committed, and in Mercy make us feel them deeply, that our Repentance may be sincere, and our resolutions stedfast of endeavouring against the commission of such in future. Teach us to understand the sinfulness of our own Hearts, and bring to our knowledge every fault of Temper and every evil Habit in which we have indulged to the discomfort of our fellow-creatures, and the danger of our own Souls. May we now, and on each return of night, consider how the past day has been spent by us, what have been our prevailing Thoughts, Words, and Actions during it, and how far we can acquit ourselves of Evil. Have we thought irreverently of Thee, have we disobeyed thy commandments, have we neglected any known duty, or willingly given pain to any human being? Incline us to ask our Hearts these questions Oh! God, and save us from deceiving ourselves by Pride or Vanity.

Give us a thankful sense of the Blessings in which we live, of the many comforts of our lot; that we may not deserve to lose them by Discontent or Indifference.

Be gracious to our Necessities, and guard us, and all we love, from Evil this night. May the sick and afflicted, be now, and ever thy care); and heartily do we pray for the safety of all that travel by Land or by Sea, for the comfort and protection of the Orphan and Widow and that thy pity may be shewn upon all Captives and Prisoners.

Above all other blessings Oh! God, for ourselves, and our fellow-creatures, we implore Thee to quicken our sense of thy Mercy in the redemption of the World, of the Value of that Holy Religion in which we have been brought up, that we may not, by our own neglect, throw away the salvation thou hast given us, nor be Christians only in name. Hear us Almighty God, for His sake who has redeemed us, and taught us thus to pray.

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/ausprayr.htmlOn the Subject of Reading Another’s Letters

“She was obliged to recollect that her seeing the letter was a violation of the laws of honour, that no one ought to be judged or to be known by such testimonies, that no private correspondence could bear the eye of others, before she could recover calmness enough to return the letter which she had been meditating over”

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/brablets.htmlViolence: Minor / Profanity: None / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

There were some “unnecessary” parts… (guys tearing their clothes off and going swimming naked) … luckily I was warned by a friend that that part was in there, so I knew where to skip past :) and another scene at the very beginning (during the opening credits) involving Janes parents. I cried SO much during this movie!! It’s unreal… great costumes, great acting, great music… bring your tissues, this movie will have you CRYING and CRYING then laughing and Crying some more!! I never liked Anne Hathaway, but she was very likeable in this film, as is James McAvoy as Tom LeFroy. The ending is so sad, what makes it even worse, is that this story is true! But, I recommend this film (with some editing)!

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Average / 4

Average / 3½

Offensive / 3

Not only where there jabs about Christian and societal oppression to women, such as the first scene where the father is preaching from a pulpit about a womens “place.” But also jabs at innocence and purity being a negative trait. My husband and I walked out of the movie disappointed and would not recommend this movie!

Average / 3

[What is true love and how do you know when you have found it? Answer]

As far as the movie itself goes, the storyline and cinematography I thought was beautiful. I thought the music was nicely done as well. The chemistry between Hathaway and McAvoy is very sweet. At times, I found the story very believable and touching. If you’re looking for an Austenian romance, look to Ms. Austen’s works themselves. I thought this film was very untrue to what Jane Austen was really like. As a follower of Christ, I encourage my brothers and sisters to compare the ideals presented in this movie with the description of worthy pasttimes described in Philippians 4:8: whatever is pure, lovely, noble, admirable, excellent, and praiseworthy. I didn’t find this film to be so.

Offensive / 4

Very Offensive / 1½

If you enjoy this genre of film then you will most likely enjoy the movie, I found it to be a tad boring when compared to films such as “Sense and Sensibility” or “Pride and Prejudice” but it is still well filmed and the acting is strong.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Better than Average / 4

Better than Average / 3½

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½

My Ratings: Better than Average / 4