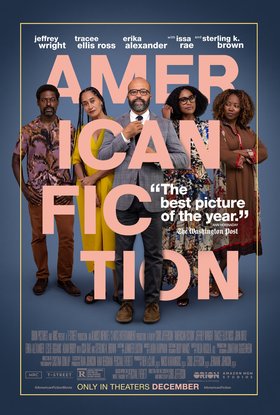

American Fiction

for language throughout, some drug use, sexual references and brief violence.

for language throughout, some drug use, sexual references and brief violence.

Check back later for review coming from contributor Jim O'Neill by Dec 23

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Dark-Comedy Satire Drama Adaptation |

| Length: | 1 hr. 57 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2023 |

| USA Release: |

September 8, 2023 (film festival) December 15, 2023 (limited) December 22, 2023 (wider—40 theaters) January 5, 2024 (114 theaters) January 12, 2024 (625 theaters) January 19, 2024 (850 theaters) DVD: June 18, 2024 |

Who is lead actor Jeffrey Wright?

Who is lead actor Jeffrey Wright?

.jpg)

This film is based on Percival Everett’s novel Erasure, which reacts against the dominant strains of discussion surrounding the publication and criticism of African-American literature.

Life and isues of novelists/authors

Novelist being repeatedly told that publishing houses don’t believe his writing to be “black enough”

The consequences of turning one’s art into a simple commodity; i.e. giving into market forces

Reducing people to outrageous stereotypes

Establishment profiting from ‘Black’ entertainment that relies on tired and offensive tropes

Parody of ghetto novels such as Sapphire’s Push

Pranks gone wrong

What does the Bible say about HYPOCRITES?

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Jeffrey Wright … Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison Tracee Ellis Ross … Lisa Ellison John Ortiz … Arthur Erika Alexander … Coraline Leslie Uggams … Agnes Ellison Adam Brody … Wiley Keith David … Willy the Wonker Issa Rae … Sintara Golden Sterling K. Brown … Clifford Ellison See all » |

| Director |

|

Cord Jefferson — directorial debut |

| Producer |

|

3 Arts Entertainment MRC Film Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Orion Pictures See all » |

| Distributor |

“For where jealousy and selfish ambition exist, there will be disorder and every vile practice.” —James 3:16 ESV

“I am so clever that sometimes I don’t understand a single word of what I am saying.” —Oscar Wilde

“Some ideas are so stupid that only intellectuals believe them.” —George Orwell

Television writer Cord Jefferson’s feature film debut, “American Fiction,” is two movies in one. The first has all the comforting elements of a network situation comedy, albeit with some dramatic charge while the other has enough satirical bite to make it a searing polemic. There is some fine writing in each of them, but by vying for space in a two-hour pas de deux, and constantly stepping on each other’s feet, the film fails to come together as a work of art or even a piece of entertaining fluff.

Much like the film “Maestro” which is making its appearance at the same time and vying for the same awards, “American Fiction” is a bevy of stirring movements in search of a solid symphony. It has the stops and starts of a rap anthem, but it lacks rhythm and a fluid style.

Jeffrey Wright gives a masterfully restrained performance, letting his long forehead and a deep furrow between his wide eyebrows do all the emoting. He plays Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, a college English professor who lives a comfortable life teaching in a respectable California college. He is also a published, but not best-selling or even moderately selling, novelist who has an inner well of anger that he gives vent to by shunning those around him, especially his family, and by goading his students.

While teaching a class on the American Fiction of the South he writes the title of a Flannery O’Connor short story, the one with the N-word in the title, on the blackboard. The microaggression charges that ensue have the potential for some dark and daring comedy, but Jefferson lets those go and shifts his glare to a faculty conference room where he zeroes in on the evolutionary endpoint of the classroom snowflake: the tenured viper.

The scene works well as a set-up for taking down the academic establishment, and it features some enjoyable collegiate-level mudwrestling, but without some follow-up crashing and burning, its branches wither and die.

Monk’s bold classroom move is rewarded with an ungracious, and unpaid, leave of absence from the college English department. He exits with his pride intact, but without prospects of another teaching position or of selling his latest novel to a publishing house, he finds himself without work, and without finances.

At this point the film veers away from satire and into sentimentality which often borders on schmaltz. Monk returns to Boston to re-unite with his family, each member of which is also having financial difficulties, despite what appears to be a privileged background. Their father was a renowned doctor. They grew up housed in a gilded suburban mansion and vacationed at a beachfront summer house. They attended elite schools where they obtained distinguished bachelor and doctorate degrees. They have a live-in servant who calls them Mister and Miss (not Doctor?). They drive Mercedes Benzes.

Such lives tend to trigger more envy than sympathy.

Ellison’s sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross) is a physician who specializes in family planning. Her hardships include having to go through metal detectors whenever she goes to work and losing all her financial assets to her ex-husband in a divorce. Neither are likely scenarios, but let’s move on.

His brother, Cliff (Sterling K. Brown—whose comic timing is perfectly tuned but does not make up for an ultimately unconvincing turn as someone who “just became gay five minutes ago”) is a cosmetic surgeon who lives in Arizona and who also claims to have lost all his money to a divorce and yet somehow is able to fund a lavish lifestyle that includes a desert bungalow, lines of cocaine, and a bevy of boyfriends.

Too bad one of the Ellison children didn’t become a divorce lawyer, or any kind of lawyer. For such smart, accomplished professionals, they all seem to end up with the short end of the stick. The three are now faced with having to care for their aging mother (a heartbreaking yet steely Leslie Uggams) who is beginning to show signs of dementia—at first slowly, and then rapidly.

They need money to care for her (another puzzle is how this coterie of the best and brightest never thought to consult a financial planner), and that is where the sub-plot, or the main plot, depending on which point of view you take, returns to the fore.

Monk is frustrated at his inability to score a publishing breakthrough. He refers to his books as novels written by a black man, but his literary agent, Arthur (John Ortiz, who gives the film its only consistent satiric edge), tells him that the public doesn’t want that, “what they want is a Black book.” The agent’s cynicism and dismissiveness for all things non-fiduciary are astounding: “Fact checkers? Nobody uses those anymore. They don’t even want to pay editors.” Such inside quips are too few, but when they come, they hit their mark, and they sting.

Monk Ellison feels betrayed by the disintegrating state of the publishing industry as well as by the taste of the public. He watches another black writer, Sinatra Golden (Issa Rae) shoot to fame with a best-selling book called “We Lives in Da Ghetto,” written in a type of street lingo that makes Alice Walker sound grammatical.

Ironically or not at all ironically when one considers today’s literary scene, Golden is the antithesis of her novel’s narrator: she is a meticulously dressed, well-spoken graduate of, get this, Oberlin College. The part is written as more type than persona, but Rae adds some fire and conviction to the veneer making Sinatra a force that lets you see how her own brand of fraud comes from something deeper than greed. When she speaks what’s on her mind you can see why her words sell.

Monk responds by writing his own memoir called “Pafology” (ghetto talk for Pathology). Ellison later changes the title to the F-word to give it some extra punch. He uses the cobbled name Stagg R. Lee as a pseudonym. No one seems to catch the folk legend analogy, but that doesn’t matter as the book goes on to sell and sell, and then be auctioned for movie rights.

The Hollywood encounters are what you’d expect: boilerplate scenes played out in cookie cutter fashion but lacking the despairing pathos of the script pitches William Holden’s Joe Gillis reels off in “Sunset Boulevard.” To what the publishing executives and the movie green-lighters are calling “raw,” “visceral” and “lived experience,” Monk replies: “but it’s trash,” and “the dumber I behave, the richer I get.”

Most of Jefferson’s satire doesn’t tear flesh; it barely registers a half degree burn. Yet some of the barbs, especially those inflicted on the academic smart set, so ripe for piñata style whacking, land like smart bombs. His targets’ comeuppances are always welcome, even though their trajectories are obvious from the start.

It makes the same mistakes that this season’s other satire, “Saltburn,” does in succumbing to one’s own egotism and smugness, although it steps back and chides itself in ways that the latter will not allow itself to do. That film, with its pornographic chicanery and disdain for humanity, makes no sense. Its prancing ending, a Salome-style dance in which the film audience is asked to become a stand-in for King Herod’s court, implies that once a narcissistic con-artist achieves his goal he has reached a Nirvana-style satisfaction.

Such a premise is laughable. That personality type is never satisfied; it only ever wants more. Monk, at least, has the self-awareness to reflect and to make amends, but the film is ambivalent about where those insights will ultimately take him.

The movie also shies away from an honest, and necessarily painful, look at greed, envy and the abandonment of honor.

“From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded; and from the one who has been entrusted with much, much more will be asked.” —Luke 12:48

Monk has his good points; some are even respectable. He honors his mother and his dead father. He takes his responsibility as a son seriously. However, he turns his back on his own ideals in a quest for the riches and fame that he covets in others. Indeed, he may be right about manufactured fame being nothing more than a joke. Best-selling books and films are often jokes. The biggest successes today have their origins in the comic pages.

A joke, however, tends to be harmless. Monk’s lie is not. But a lie, as we learn in the third chapter of Genesis, is almost always more convincing, and more comforting, than a hard truth. The twentieth century was a testament to the power of such comfort. Many of the best sellers of those years: “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male,” “Coming of Age in Samoa,” and “The Population Bomb” were huge sensations and widely acclaimed.

And they were all lies.

Jefferson makes a good point in his movie when a character says that to make people believe a lie you must put it right under their noses, something akin to Joseph Goebbels saying that if you want people to believe a lie, “make sure it’s a big one.”

Sadly, the director sidesteps his own keen observation and delivers several whoppers of his own, topped off with a puzzling ending that shrinks his story to a two-dimensional set piece. By concluding with a series of movie props and costumes is he saying that life is nothing more than an imaginary and quickly dismantled soundstage?

Each one of us is given a voice here on earth. And a task. A philosopher reminds us that we may not come to know what that task is on this earth, but we will be told what it is in the next. The story of Thelonious Monk could have been a cautionary tale of what happens to us when we deny a calling and refuse a cross, but by straying from the linear direction of the cross and turning in circles, “American Fiction” ultimately goes nowhere.

- Profane language: Very Heavy

- Vulgar/Crude language: Very Heavy

- Wokeism: Heavy

- Sex: Moderate

- Violence: Moderate

- Drugs/Alcohol: Moderate

- Nudity: Minor

- Occult: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

As much as we hear how others want “Black people to get their act together,” that’s not true. When it happens, others react with thinly veiled criticism (as the reviewer did in his comments about the family’s affluence, which had NOTHING to do with the plot). Their superiority is threatened. Rather, they WANT to see the stereotypes of dysfunction and “ghetto” life; they are entertained by it. They feel better knowing that they are “above” this.

I’ve experienced this myself, as a woman from an upper-middle class Black family of professionals: the condescending remarks about our accomplishments. The jokes about “you’re not REALLY Black, though.” The questions about “why am I not like REAL Black people.” Wondering if I would “sing or rap” for them. People WANT to see what the stereotypes they have come to believe through media and TV.See all »

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5