Fever Pitch

for crude and sexual humor, and some sensuality.

for crude and sexual humor, and some sensuality.

Reviewed by: Dr. Kenneth R. Morefield

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Teens Adults |

| Genre: | Sports Romance Comedy |

| Length: | 1 hr. 41 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2005 |

| USA Release: |

April 8, 2005 |

For a follower of Christ, what is LOVE—a feeling, an emotion, or an action?

What is true love and how do you know when you have found it?

Learn how to make your love the best it can be. Christian answers to questions about sex, marriage, sexual addictions, and more. Valuable resources for Christian couples, singles and pastors.

Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

How far is too far? What are the guidelines for dating relationships? Answer

What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

| Drew Barrymore, Jimmy Fallon, Lenny Clarke, Jack Kehler, James B. Sikking |

| Director |

|

Bobby Farrelly, Peter Farrelly |

| Producer |

| Alan Greenspan, Amanda Posey, Gil Netter, Drew Barrymore, Nancy Juvonen, Bradley Thomas, David Zucker |

| Distributor |

Here’s what the distributor says about their film: “Jimmy Fallon and Drew Barrymore star in the second film adaptation of Nick Hornby’s (‘High Fidelity,’ ‘About a Boy’) autobiographical novel documenting a love triangle between a man, his woman, and his beloved sports team. This American version changes the object of the protagonist’s obsession from soccer to baseball. The film is rated PG-13 for some crude humor and sexual situations. It is directed by the Farrelly Brothers.”

I could spend three reviews writing about how and why the new “Fever Pitch” is inferior to the 1997 version starring Colin Firth or the 1994 semi-autobiographical novel by Nick Hornby and never get around to providing solid information about this film for the benefit of the uninitiated. So let me start by saying if you are not a Firth fan, a Hornby fan, a Yankees fan, or an intelligent movie fan, you probably won’t be disappointed by this watered-down version of a pretty good story. You may even be entertained by it; I know I would have been, if I could have stopped counting the ways it should have been better.

Hornby’s novel is about a young man obsessed with a perennially losing soccer team and the toll that this obsession takes on his personal relationships. That our film moves the action from England to America and changes the sport from soccer (or football, as the rest of the world calls it) to baseball actually ends up being the least egregious of its changes. The 2005 film has been dumbed-down and the hero made much more sympathetic as a means of making the film more palatable to a mass audience.

How has it been dumbed-down? Our hero’s name is now Ben Wrightman (get it?), and his intended is Lindsey Meeks (get it yet?). Hey, I wonder if the names are symbolic? Symptomatic of the film’s laziness (besides the fact that it just borrows a whole premise from another movie made less than 10 years ago and still widely available on DVD) is its treatment of Lindsey’s “job.” We get one thirty second product placement (that will look oddly familiar to anyone who has seen “The Apprentice”) to tell us what she does, followed by a series of references to a “project” that Lindsey has to do in order to get a “promotion.”

The generic dialogue shows that the movie, like its hero, isn’t really interested in her—at least not interested enough to research an actual job that an actual person might have and thereby help us to see her as an actual person.

One of the pleasures of the 1997 film was the way that it took a general situation and managed to rise about the sitcom level by presenting us with two very real people. Sitcoms are about situations, engaging movies (even comedies) about people; sitcom couples have miscommunications—easily and completely resolvable within a twenty-three minute arc. Engaging movie couples have real differences. The interest generated by a superior romantic comedy comes in watching how, if at all, the characters are able to negotiate those differences and forge a healthy relationship.

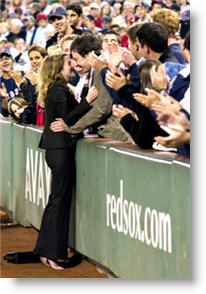

The ending of the 2005 film is wholly unsatisfying precisely because it resolves nothing; none of the (watered-down versions) of the conflicts introduced are actually addressed: the resolution consists of the characters deciding, “Hey, maybe its not such a problem after all.” The mind is its own place, as Milton’s archetypal unapologetic narcissist once said; perhaps wishing will make it so.

Ultimately, the most damaging change to the material comes in the attitude the film takes towards the Ben/Paul character. A large part of the what made the 1997 film work was Paul’s own awareness of and discomfort with his unhealthy obsession. In one nicely done scene, his girlfriend (called Sarah in the earlier film) asks him what he is thinking about, and he says “D.H. Lawrence.” Pleased that he is contemplating a topic that she can share, she tries to draw him out by asking him a series of questions about his thoughts, until he sheepishly confesses that he had, in fact been thinking about his soccer team, Arsenal.

When Sarah asks Paul why he lied about what he was thinking about, he says in a perfectly self-aware moment of lucidity: “Well, the answer can’t always be Arsenal, can it?” Of course, it can’t, and he knows it. His resentment towards Sarah is not caused by her failure to understand the seemingly benign nature of his passion;, it is caused by the fact that her mere presence brings to the foreground his own ambivalent feelings towards the shell of a life his addiction has helped create.

I’m not asking for a “Friday Night Lights” indictment of sports as idolatry here, but “Fever Pitch” is so indulgent towards Ben’s character flaws that it refuses to ever let us ever take Lindsey’s side for more than fifteen seconds. After that, she and her three dimensional emotions must be shipped off screen so that Ben can exhibit character growth by looking slightly less happy at a few Red Sox games.

Take for example Lindsey’s possible pregnancy. In the 1997 film, Sarah actually gets pregnant, and Paul can’t hide the fact that he is more interested in a possible apartment’s proximity to the stadium than he is in its suitability for raising a family. In the 2005 film, Ben’s caddishness is seriously softened: Lindsey springs the possible pregnancy on Ben in a pique after he declines to make a last minute weekend trip to Paris with her and then calls him from overseas to announce that it was a false alarm.

The film’s treatment of Paul is a giveaway that, like most contemporary entertainment films, its target audience consists primarily of adolescent boys and young men. If the ’97 film was about the costs of growing up, the ’05 film argues that you can have it all: you can have your friendships continue to take precedence over your family or job, you can have really good tickets to premium sporting events without having to pay for them, and you can even have a really, really, hot chick who will gladly forego the privileges of being a wife for the joys of being baseball buddy who will also have sex with you.

Leslie Fiedler argued in Love and Death in the American Novel that so many classic American texts were about men trying to avoid women because women meant domestication and, with it, adulthood, responsibility, and, finally, death. The Farrelly brothers Americanize “Fever Pitch” by taking a story about the moment when a man stops fighting to remain a child and reworking it to say that maybe he doesn’t have to stop after all.

“When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put childish ways behind me” (1 Corinthians 13:11).

My Grade: C+

Violence: None / Profanity: Minor / Sex/nudity: Mild

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Average/4

Average/3½

Drew Barrymore and SNL cast member Jimmy Fallon (who, in real life, is a Red Sox fan) look like a really cute couple but the two of them have almost zero chemistry. Despite the good things about “Fever Pitch” (humor, baseball, and a sweet love story), pre-marital sex plays a part in the movie as well as some sexual humor and a few cuss words here and there. This film is appropriate for only mature teens and anyone who is a passionate Red Sox fan.

Average/3

I fully agree that the extra-marital situation in the movie was wrong and disappointing, but weighing that portion of the story with the remainder of the movie doesn’t detract from the overall theme of trying to wrestle with 2 loves… baseball and true love. And “obsession” would be accurate, because anyone with Red Sox shower curtains and underwear is over the edge… wouldn’t you agree??!! Hey, I don’t have ANY Cubs undergarments.

I was pleasantly surprised by Jimmy Fallon’s acting and how well he fit this role… better than I expected, considering how lousy Saturday Night Live has become over the past 10 years. And once the movie got past an awkward introductory phase, Drew Barrymore did a fine job too. Considering it’s directed by the Farrelly Brothers, it’s a surprisingly mild film with little evidence of the sophomoric and immature humor of their past films.

Keep in mind, this ain’t no Oscar performance, and it ain’t no “Bull Durham” or “The Natural” or “Field of Dreams,” but it’s a nice movie, and I’d say it’s a good date flick, too. I’d give it a 3-½ out of 5. And you don’t have to be a Red Sox fan to enjoy it. Just insert your own favorite team. As a Cubs fan, it worked great for me… the pain was sustained throughout the entire film. And the part of me that’s a Cardinals fan was hurt even more by the final shots in Busch Stadium during the World Series. Emotional trauma? What emotional trauma?!?!

By the way, we didn’t see any trailers before the movie. We were subjected to… I mean, we watched a teaser for a new FOX-TV animated show titled “American Dad,” which I think is scheduled for Sunday nights alongside The Simpsons, King of the Hill, and Family Guy. I’ll be totally and brutally honest here… it’s ABSOLUTELY AWFUL!!!… If the actual show is anything like what we saw, avoid it at all costs. You’ve been warned.

Average/3½

Better than Average / 4

Better than Average/4

My Ratings: Offensive/4