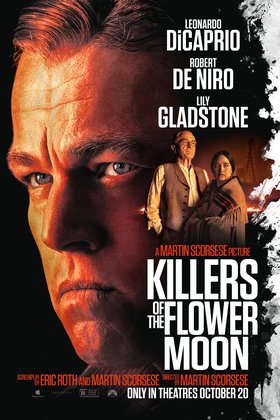

Killers of the Flower Moon

for violence, some grisly images, and language.

for violence, some grisly images, and language.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Western Crime Drama History Adaptation IMAX |

| Length: | 3 hr. 26 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2023 |

| USA Release: |

October 6, 2023 (limited) Apple TV: October 20, 2023 DVD: January 25, 2024 |

Timeframe: 1920s USA

Cattleman William King Hale, a political boss of Osage County, Oklahoma who made his fortune through a mix of cattle ranching, unfair trade with Osage people, insurance fraud, and various murder and fraud schemes

Osage tribe of Native Americans (Osage County, Oklahoma)

Big oil wealth beneath American Indian land

Greed and ruthless scheming for profit

The evil in men’s hearts and the poison they spread

A major F.B.I. investigation involving J. Edgar Hoover

Serial wanton murders of Osage tribal members to obtain their oil money, while local authorities turned a blind eye

About the fall of mankind to worldwide depravity

What is SIN AND WICKEDNESS? Answer

What is JUSTICE? What does the Bible say about it? Answer

In 1925, the United States Congress passed a law to bar the inheritance of Osage headrights by non-Osage people in order to curb the Osage Indian Murders.

For a follower of Christ, what is LOVE—a feeling, an emotion, or an action?

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Leonardo DiCaprio … Ernest Burkhart Robert De Niro … William King Hale Lily Gladstone … Mollie Burkhart Jesse Plemons … Tom White Tantoo Cardinal … Lizzie Q John Lithgow … Prosecutor Peter Leaward Brendan Fraser … W.S. Hamilton Cara Jade Myers … Anna Janae Collins (JaNae Collins) … Reta Jillian Dion … Minnie Jason Isbell … Bill Smith William Belleau … Henry Roan Louis Cancelmi … Kelsie Morrison Scott Shepherd … Byron Burkhart See all » |

| Director |

|

Martin Scorsese |

| Producer |

|

Appian Way Apple Studios See all » |

| Distributor |

“For we brought nothing into the world just as we will be able to bring anything out of it…

those who want to be rich are falling into a temptation and into a trap.

And into many foolish and harmful desires which plunge them into ruin and destruction.” —(1 Timothy Chapter 6-9)

“Abundance of riches will never pay our ransom to God. That price is far too high. When we die, we take none of what we accumulated or hoarded with us. When the rich man dies, his wealth will not follow him down.” —Psalm 49

Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon” is epic in its length, its scale, and its undoing.

The film is based on the non-fiction bestseller of the same name by David Grann. A journalist by profession, Grann relates the Osage saga with detached precision allowing unfolding events and mounting evidence to point to a conclusion whose surface defies belief but whose depths cry out for acknowledgment and atonement.

Scorsese, on the other hand, goes off track by straying from a firm narrative, losing focus by morphing an austere Western setting into a kaleidoscopic dreamscape, and most of all, by expanding one crime, or set of crimes, into an entire legacy. When a singular evil such as the one depicted in this film becomes comparable or generalizable, its singularity and its ability to alarm and to warn is diluted.

The crime perpetrated on the Native Americans of Osage County, Oklahoma in the early 1920s stands alone in its barbarity and inhumanity. Scorsese would have us believe that this horror is not just a stain on the country’s heritage, but an emblem of what the frontier represented, and what American civilization still represents.

That’s a reach, one that is unfair, and unfounded.

Scorsese’s prior films, especially the ones about American gangsters, directed a cold eye toward wrongdoing, yet they reveled in the almost irresistible allure of crime. The tracking shot in the opening scene of “Goodfellas” makes us dizzy as we take in every temptation known to man, warning us but teasing us at the same time. On the one hand, he tells us, we’re headed to perdition; on the other, there’s a heck of a lot of money, and fun, to be had along the way.

That same duality does not exist in the tragic story of the Osage Native American tribe, or for that matter, in any Western. In such a landscape, unfamiliar territory to him, Scorsese creates some memorable moments, but overall, he seems adrift and, despite a huge budget to cater to his every artistic wile, is sadly out of his element.

In the 1870s the Osage Indian tribe had been driven from its ancestral land in Kansas and resettled in Oklahoma on property that was rocky, barren and not suitable for farming and hunting. After being given ownership of that land they discovered that it sat upon huge oil deposits. Prospectors then descended upon Osage, but to extract oil from the ground they had to rent leases from the Osage tribespeople. The white citizens of the county resented the wealth of the “red millionaires,” and set up guardianships that placed the Native Americans under their thumbs. The Osage could not appropriate or spend any of the revenue from the sale of their oil unless it was approved by a white citizen. The guardians manipulated and exploited their charges, but even that graft had its limits. The guardian had no hold on the actual land rights which could not be stolen or even bought. Those rights could only be inherited.

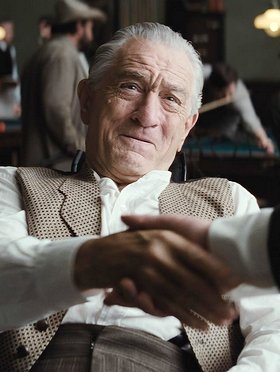

The film deals mainly with a white family’s attempt to seize an Osage family fortune by deceit, theft and murder. William Hale (Robert De Niro, an Oklahoma cattle rancher, enlists his dim-witted and obsequious nephew, Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) to marry Mollie (Lily Gladstone), a wealthy Osage woman, for Ernest and his uncle to inherit her estate. Hale’s follow-up plan is to do away with Mollie and her family so Ernest can inherit her fortune. Mollie, played with quiet dignity by Lily Gladstone in a standout performance that betters DiCaprio’s bloated and self-conscious one, longs for love and fulfillment, but is wary of promises made by her husband and his uncle. She is smart and perceptive enough to see through their sweet talk, but she is nonetheless willing to put blinders on to forge stability and hope.

During Ernest and Mollie’s courtship and marriage, Mollie’s sister is shot to death, and her mother dies of an unidentified “wasting illness.” Soon afterwards Mollie develops the same illness. As similar unexplained deaths among Mollie’s family and other Osage natives mount, none of which generate a serious local police investigation, the FBI, then in its infancy, is called in to find a cause for the mysterious tragedies. The bureau’s young director, J. Edgar Hoover sends a former Texas Ranger, Tom White (Jesse Plemons) to Osage to investigate and solve the murders.

Scorsese handles the developing crime and corruption phase of the story well. He creates a seething cauldron of envy, greed, anger and malice in which the evildoers forget many things, most of all, that none of us are landowners, but tenants in a vineyard leased to us. We can choose to bear fruit on that land, or we can, as Isaiah warned, become the wild vines, that produce only ruin. The director shines in imagery that reveals cultural rot in a way that is more visceral than analytical, but when the real crime-fighting gumshoe work needs to take front and center, he wobbles.

I don’t doubt that Scorsese wanted to avoid bogging down his story with procedural detective minutiae, but that doesn’t necessarily have to put a drag on a movie, especially a long one whose duration already has a built-in drag. Zooming in on the details of police work can enrich a crime story as it did in Kurosawa’s 1963 film, “High and Low,” also a long one, but always riveting, one of the best crime procedurals ever filmed. Scorsese’s movie staggers during those sequences, losing its momentum and its grip.

The ensuing trial sequences are even more lumbering. Most of John Lithgow’s portrayal of the prosecuting attorney is done vocally without any visual exchange between him and the defendant. It’s a performance that could have been done in a sound studio and mailed in. The courtroom scenes are murky and lack any sense of atmosphere, drama, or even coherence, and their conclusions don’t sting the way they should. Worst of all, instead of ending with written words on the screen that modestly tell what happens to the title characters in his film, Scorsese turns his finale into a radio serial extravaganza that in its grandiosity puzzles more than it illuminates. Instead of a sober and dignified closure he opts for “puttin’ on the ritz.”

Mr. Scorsese’s films are richly dressed, as if made of purple and fine linen, but the more sumptuous they become, the more vacuous they feel. He reaches for Icarus-level heights, and at times he attains them, without burning himself, but there’s a loftiness, and an affectedness in this film and in his other recent efforts that overwhelm, and after a while, fatigue.

The story of the Osage Native Americans is a sobering account of how prejudice can infect a mind to the extent that injustice can be called justice, and genocide, emancipation. It is not a big step from forgetting who reminded us that “I am the Lord, your God” to forgetting everything that followed about coveting, stealing and killing.

The Osage story has historical significance, but it is also transcendent. The Indian culture understands that, refusing to separate its corporal from its spiritual understanding of existence. Scorsese must feel that same anthropological pull, but he shies away from it, in the same way he did with the feckless confessional ending of “The Irishman.”

When the time for tears and penance comes, the fiery director’s purpose often goes up in smoke. And his smoke signals, unlike those of the Indian tribes he portrays, are, intentionally or not, hazy and hard to read.

- Violence: Very Heavy

- Drugs/Alcohol: Very Heavy

- Profane language: Heavy

- Vulgar/Crude language: Heavy

- Sex: Moderate

- Wokeism: Minor

- Nudity: None

- Occult: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.