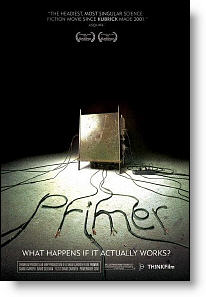

Primer

for brief language.

for brief language.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Better than average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults Teens |

| Genre: | Sci-Fi Thriller |

| Length: | 1 hr. 18 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2004 |

| USA Release: |

October 8, 2004 (limited) |

time travel

the ethics/morality of altering your former self

scientists at work—What is it really like?

What scientific discoveries have been made accidentally?

| Featuring |

|---|

| Shane Carruth, David Sullivan, Casey Gooden, Anand Upadhyaya, Casey Gordon |

| Director |

|

Shane Carruth |

| Producer |

| Shane Carruth, David Sullivan |

| Distributor |

| ThinkFilm |

“If you always want what you can’t have, what do you want when you can have anything?”

Here’s what the distributor says about their film: “Four amateur inventors are surprised by the success of their latest breakthrough, an extremely powerful device which has the potential to change the world forever.”

prescient: having foresight; having or showing knowledge of events before they take place

Shane Carruth’s debut movie, “Primer”, which he wrote and directed, is comparable to Blair Witch Project in that it is a home-made thriller working within a conventional genre. In this case, the genre is sci/fi. Just as “Blair Witch…” transcends the horror genre’s use of space by expanding the psychology of time, “Primer” transcends the sci/fi genre’s use of time by expanding its psychological space. In “Blair Witch…,” the characters travel from present space to past space; in “Primer”, the players travel from present time to past time. In both, the real journey is in the mind where they discover (create?) things about themselves and one another that they never knew existed.

The premise of “Primer” is simple: four friends, all engineers, work in Aaron’s (Shane Carruth) garage on a vague project. Their putative purpose is to make money. They manipulate the stock market once or twice, vaguely mention “venture capital,” and offer obscure allusions to doing “something charitable” and finding an “application” for their device. Such references are just sufficient to maintain the fiction that the plot revolves around whether to live ideally or materially. At one point, Aaron and Abe (David Sullivan) fantasize about what they would do with unlimited wealth. It’s a sham thread because Carruth has much bigger fish to fry, beginning with his own unique idea of time travel.

In the same way that Marcel Duchamp explored the concept of “found art” through the device of an upside down urinal, the young engineers use “found” components to assemble their conceptual device. They cannibalize parts from a microwave, a refrigerator, and even the catalytic converter from Aaron’s car. As the voiceover portentously notes: “They took from their surroundings what was needed and made of it something more.”

Once they have their device perfected, they emerge from its dark, womb-like container, saying, “That’s the most content I’ve ever been.” In fact, crawling out of the hot box causes a stinging electric shock. How, then, does one explain the anomaly of the statement other than to suppose that Carruth is throwing us an existential bone to chew on? Are they “conTENT” or are they “CONtent”?

Clearly, Carruth is playing some riffs on the themes of being and becoming, but more importantly he is exploring a metaphysical dimension to time. As I see it, Carruth’s rather brilliant contribution to the genre is in exploring the psychological ramifications of simultaneous selves living in competition with one another.

This is how it works: Aaron and Abe construct containers which allow them to travel in time. They secretly keep these containers (where else?) at a U-Haul storage facility, richly playing off the conceptual conflict between static space and fluid time. They observe themselves entering in and coming out of the facility on different occasions and begin to speculate about their “duplicates,” as if the duplicates have an agency that is indeterminate. “What do they do?” they ask one another concerning the duplicates’ actions.

That idea seems to take root as the primary characters themselves become unstable in their thoughts and actions and deceive one another in gradually escalating degrees. The film concludes with Aaron saying (if I remember correctly) “Put them one and a half meters apart.”

At this point, one concludes that Aaron has all the money he needs and that the only thing he can be referring to are the devices. Carruth subtlely shows how Abe and Aaron respond differently to the potential of the device. Abe seems to constrain his desires within the material realm; Aaron looks increasingly unhinged. One further concludes that Aaron is no longer interested in money. Or even in people.

The mind-blowing possibility that suggests itself is that the unshaven, wide-eyed Aaron has acquired a megalomaniac desire to manufacture endless numbers of duplicate selves by the simple expedient of crawling in and out of the devices’ womb-like environments in succession. The concept of duplicate selves co-existing in the same space with conflicting intentions is a brilliant paradox.

The scenarios that subsequently present themselves are similar to that encountered by Schwarzenegger’s character in “Sixth Day” when he sees his clone clowning with the wife. Similarly, in “Primer” one sees the yawning abyss of murderous intent through the device of a minor sub-plot whose purpose is to suggest the beginnings of a psychological breakdown in one of the characters.

Identity is a tenuous and interesting construct, but it’s one that’s been explored in many recent films like “Fight Club” and “Memento.” Primer’s brilliance lies in exploring the metaphysics of self, through the duplication of self, by the infinite attenuation of self in time. What “Primer” suggests is that although the boundaries of time, even in time travel, are limited to six hours, those six hours are full of infinite possibilities and contain the potential for multiple selves. The movie touches on the possibility that “duplicates” could be active agents in the same day, with conflicting purposes, based upon different interpretations of actions caused by the other duplicates or by the duplicates of the other friend when their own relationship begins unraveling as well.

The permutations are mind-boggling and neither the movie nor anyone other than God can give an answer to such an open equation. “Primer” plunges yet another fathom deeper into psychological waters by giving us a look into the mind of someone who, Kurtz-like, peeks into the abyss and teeters on the edge of madness. In “Heart of Darkness,” Conrad at least provided the release of an Aristotelian catharsis through Kurtz’s remorseful utterance: “The horror. The horror.” We don’t quite get that response in “Primer”.

The voice-over explains one of the god-like powers of their new-found causality as: “We had but to speak the words that came into his head and he’d follow the script.” Abe reassures Aaron that they retain control, saying: “We know everything, okay? We’re prescient.”

We know everything.

We’re prescient.

Contrary to the rules of the stage and physics, in “Primer,” it is the present that is prologue. In Carruth’s conception of time as expressed in those sentences, phenomenology and epistemology collide and fracture into meaninglessness: to know and to be no longer mean anything. In normal existence, the natural world is a fixed object and therefore a reliable subject of either knowing or being; in Primer’s reality, the natural world is a house of mirrors: nothing is ultimately knowable, and no existence is ultimately reliable since both can be undermined by a duplicate.

Aaron and Abe know nothing for certain other than that they exist in many presents. Within a six-hour time-frame, existence is functionally infinite because wherever they are they can use an existing box to return yet another six hours in the past and so on, multiplying themselves and their actions with resulting and unpredictable causalities.

Finally, there is the matter of the title. Does the title implicate time as a “primer” upon which we inscribe self and history? The movie suggests that reality is a dynamic palimpsest with a primer covering a previous version even as it prepares to receive the succeeding one, mediating between past and present in a modality that is very much like time travel. Carruth’s vision of time is original and provocative, but what’s more impressive is that he introduces a second brilliant idea by portraying the psychology of a character who is the first human being to glimpse the multiple possibilities of human contingency in the vast continuum of Time.

In the end, Aaron falls to the old temptation of wanting to know what God knows, to see as God sees. His plight brings to mind Milton’s Lucifer who rationalized: “The mind is its own place / And can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.” Endless trips through hot boxes may very well be Aaron’s own special hell. The illusion of infinite power, even in the midst of great personal misery, is the ultimate heaven reserved for a fallen mind plunging down an infinite abyss.

Editor’s Note: “Primer” won an award at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival. It was reportedly made for just $7,000 by a professing believer named Shane Carruth, the director/writer/star.

My Ratings: [Average/1]