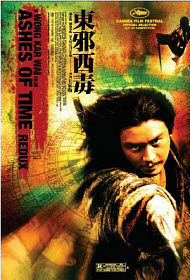

Ashes of Time Redux

for some violence.

for some violence.

| Moral Rating: | not reviewed |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Action Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 33 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2008 |

| USA Release: |

October 10, 2008 (exclusive NYC/LA—5 theaters) DVD release: March 3, 2009 |

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Maggie Cheung Tony Leung Chiu Wai Charlie Yeung Li Bai, Jacky Cheung, Leslie Cheung, Carina Lau, Tony Leung Ka Fai, Brigitte Lin |

| Director |

|

Kar Wai Wong |

| Producer |

| Jet Tone Production (Hong Kong), Ye-cheng Chan, Jeffrey Lau, Tsai Mu Ho, Jacky Pang Yee Wah, Kar Wai Wong |

| Distributor |

Here’s what the distributor says about their film: “A broken-hearted hit man moves to the desert where he finds skilled swordsmen to carry out his contract killings.”

ASHES OF TIME is inspired by characters from Louis Cha’s martial arts novel The Eagle-Shooting Heroes. It centers on a man named Ouyang Feng. Since the woman he loved rejected him, he has lived in the western desert, hiring skilled swordsmen to carry out contract killings. His wounded heart has made him pitiless and cynical, but his encounters with friends, clients and future enemies make him conscious of his solitude…

The film is set in five parts, five seasons that are part of the Chinese almanac. The story takes place in the jianghu, the world of the martial arts. Ouyang Feng (Leslie Cheung) has lived in the western desert for some years. He left his home in White Camel Mountain when the woman he loved chose to marry his elder brother rather than him. Instead of seeking glory, he ends up as an agent. When people come to him with a wish to eliminate someone who has wronged them, he puts them in touch with a swordsman who can do the job.

J I N G Z H E

In the Chinese almanac, which divides the year into 24 terms, Jingzhe is the third solar term. It begins when the sun reaches 345 degrees of celestial longitude and ends when it reaches 360 degrees. It refers to a time in spring when the peach blossom flowers begin to bloom and insects come back to life. Every year, as spring approaches and the almanac predicts warmer breezes from the east, Ouyang Feng receives a visit from his friend Huang Yaoshi (Tony Leung Kai Fai). In their younger days, Huang and Ouyang were the two best swordsmen of their generation. Huang is a dashing romantic and a roaming adventurer. Like a sworn ritual, he visits every year at the same time to tell Ouyang tales of his travels of that year.

This year Huang brings a gift for Ouyang—a magic wine, given to him by a woman, which is said to erase the drinker’s memories. Ouyang declines to drink any. But Huang, having drunken the wine himself, leaves abruptly, leaving Ouyang to wonder who the woman is.

Soon after, Huang meets a swordsman (Tony Leung Chiu Wai)in a tavern, and asks him if they knew each other from before. The swordsman replies in the affirmative, and says that the two of them used to be best friends. Huang had previously gone to Peach Blossom Village to attend the swordsman’s wedding, but Huang flirted with the bride (Carina Lau) on their wedding day. Since then, the swordsman has sworn to kill Huang the next time they meet. But despite his oath, the swordsman does not kill Huang Yaoshi that day, for he is turning blind. Huang instead is later wounded in a duel with the Prince of the Murong Clan, who accuses him of jilting his sister.

Business is slow for Ouyang Feng. He has only one client this spring. That client is Murong Yang (Brigitte Lin), who commissions the death of Huang Yaoshi. Huang’s crime is that he jilted Murong’s sister Yin; Huang had proposed to marry Yin a year ago but never showed up. Murong wants to administer the deathblow himself, to ensure that Huang dies in excruciating pain. Soon after, Ouyang is confronted by Murong Yin herself. She wants to commission him to organize the murder of her brother Murong Yang. During a hallucinatory night, Ouyang comes to realize that Yin and Yang are two facets of the same troubled soul. The next day, Murong disappears. A rumor later spreads through the jianghu of a mysterious swordsman who duels with his own reflection in the water.

X I A Z H I

In the Chinese almanac, Xiazhi is the tenth solar term. It begins when the sun reaches 90 degrees of celestial longitude and ends when it reaches 105 degrees. It refers to a time in summer when the influence of ‘yang’ begins to wane and ‘yin’ begins to rise. A peasant girl (Charlie Young) appears outside Ouyang’s shack. She wants to find a swordsman to avenge her brother, but has only a mule and a basket of eggs to offer in payment. Ouyang tells her that he cannot help her without money. The swordsman from Peach Blossom Village arrives. He is fast losing his sight, and wants to go home to see peach blossoms one last time while he can. But he needs money for the journey. Ouyang offers him the job of defending the local villagers from a large gang of horse thieves. They had been beaten in an earlier clash, and were expected to return soon. On the morning of the bandits’ arrival, as the near-blind swordsman goes out to confront them, he impulsively kisses the peasant girl, who is still waiting for a champion to act on her behalf. Handicapped and heavily outnumbered, he goes into battle and is killed.

B A I L U

In the Chinese almanac, Bailu is the fifteenth solar term. It begins when the sun reaches 165 degrees of celestial longitude and ends when it reaches 180 degrees. It refers to that time in autumn when the northern birds begin to migrate southwards. A disheveled swordsman, Hong Qi (Jacky Cheung), hungry and shoeless, takes up residence by a wall near Ouyang’s shack. He rides a camel and is looking for adventures in the jianghu. Despite misgivings, Ouyang feeds him and offers him the job of finishing off the remaining horse thieves. Hong Qi accomplishes this with little trouble, and goes on to help the peasant girl by avenging her brother; she ‘pays’ him with one of her eggs. Hong Qi loses a finger in the second swordfight, and falls sick. Ouyang refuses to send for a doctor, and so the peasant girl nurses him back to health herself before leaving. Hong Qi’s wife (Bai Li) appears, determined to accompany him through the jianghu, and refuses to take his “no” for an answer. On a day that the almanac notes is “extremely favorable for the North”, he leaves with her across the desert. Seeing Hong Qi and his wife depart stirs Ouyang’s memories of his romantic failure in White Camel Mountain.

L I C H U N

In the Chinese almanac, Lichun is the first solar term. It begins when the sun reaches 315 degrees of celestial longitude and ends when it reaches 330 degrees. It refers to the end of winter and the beginning of spring. Ouyang visits Peach Blossom Village and encounters the blind swordsman’s widow (Carina Lau). He immediately realizes that there are no peach blossoms to be seen; Peach Blossom is the woman’s name.

Meanwhile, Huang is recalling his last meeting with the woman (Maggie Cheung) who jilted Ouyang. She was ill and alone with a young son; her husband has died. Her decision to spurn Ouyang Feng now causes her grief. It was she who gave Huang the bottle of magic wine for Ouyang. She dies soon after. Huang then reveals that his yearly meeting with Ouyang was a pretext for Huang to visit this woman every year, bringing her news of her true love.

Not long after, Huang goes into a hermetic retreat but eventually rises to great prominence in the jianghu. He later becomes known as the Lord of the East.

J I N G Z H E

This year, Huang does not come to visit Ouyang in the desert. Ouyang receives a message from White Camel Mountain, informing him that the woman he loves had passed away in the winter two years ago. He contemplates the reasons for his solitude. As predicted in his horoscope, he was orphaned young and has never married. He reflects upon his realization that he has avoided rejection by rejecting others first.

On a day that the almanac notes is “auspicious for moving West”, he sets his shack ablaze and sets off for White Camel Mountain. He, too, rises to great prominence in the jianghu. He later becomes known as the Lord of the West.

Into the “Jianghu”

The Jianghu—literally, “Rivers and Lakes”—is the parallel universe in which martial arts fiction is set. It is a universe that often intersects with our own: real historical figures sometimes appear in it, and it often incorporates real places and events. The sprawling casts of characters in martial-arts novels mirror the complications of real-life extended families in the Confucian tradition, just as the feuds and rivalries between factions mirror the skirmishes and wars between clans which have occurred throughout China’s history.

But there are also crucial differences between the jianghu and the world we know. Many aspects of social organization are absent, and individuals—both heroic and otherwise—define their own morality. The characters are generally larger (or smaller) than life, capable of superhuman feats in controlling their own qi (vital energy), and gender is somewhat more fluid than it is in the workaday world. Exotic martial skills are elaborated fantastically, and those who have mastered them take equally exotic and fantastical noms de guerre, such as “Malignant Lord of the East” or “Malicious Lord of the West”. Supernatural forces can come into play. Most striking of all, the conventional laws of physics can be suspended: when the need arises, these people can fly.

The literary genre dates back at least to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD), when various orally transmitted tales about the heroes of a rebellious uprising against the government of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126 AD) were formalized into the prose romance translated as The Water Margin or Outlaws of the Marsh. (Louis Cha explicitly situates his own martial-arts novels in a tradition dating back to the oral storytelling of the Song Dynasty.) Jianghu romances became massively popular in the late Qing Dynasty and in early republican China (the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the western calendar), and by the late 1920s many had been adapted for the movies. In fact, wuxia pian—“martial chivalry films”—were the most popular indigenous Chinese genre produced by the Shanghai film industry in its early years, and some stories were spun out to twenty or more feature-length episodes. The genre was banned by Chiang Kai Shek’s KMT government in 1931; it was seen to risk promoting sedition and lawlessness.

The communist government which came to power in China in 1949 was no more friendly towards the genre than the KMT had been, but jianghu novels and films made a spirited comeback in the Hong Kong of the 1950s—an example soon followed by Taiwan. Jin Yong (Louis Cha) began serializing jianghu novels in 1955, achieving great popularity and gradually emerging as the greatest writer the genre had even produced. A little lower in the pantheon sits the Taiwanese jianghu novelist Gu Long, best known in the west for the long series of films made from his books by Chu Yuan at Shaw Brothers in the 1970s and 1980s. And while these new novels were appearing, many classics from the 1930s and earlier were reprinted, creating a new generation of fans and genre historians.

The coming-of-age of the wuxia film genre is usually located in the mid-1960s, when King Hu made COME DRINK WITH ME (1965) and Zhang Xinyan and Fu Qi made THE JADE BOW (1966). King Hu went on to take the tradition to new heights in Taiwan with DRAGON GATE INN (1966) and A TOUCH OF ZEN (1969); meanwhile Zhang Che and other directors at Shaw Brothers pushed into a more macho and bloody direction, paving the way for the unarmed combat kung-fu films of the 1970s which made Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan world famous. The old genre traditions were brought back by the ‘new wave’ director Tsui Hark, whose debut film was the jianghu classic THE BUTTERFLY MURDERS (1979) and whose first big-budget special-effects extravaganza ZU: WARRIORS FROM THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN (1983) was inspired by a martial-arts novel by Li Shanji first published in 1930.

In recent years, thanks to Wong Kar Wai, Ang Lee and Zhang Yimou, a much larger western audience has found its way into the jianghu. ASHES OF TIME (1994) and CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (2000) are films that pay their dues to their ancestors in the genre while inflecting the jianghu with modern ideas about psychology, sexuality and existential loneliness. Zhang Yimou’s HERO (2002) and HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS (2004) owe less to the genre’s history and more to an imaginative re-reading of China’s history, but they are none the less rooted in the jianghu. Either way, the jianghu rules.

About swords in the Bible

About swords in the Bible