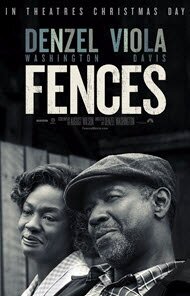

Fences

for thematic elements, language and some suggestive references.

for thematic elements, language and some suggestive references.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Drama Adaptation |

| Length: | 2 hr. 18 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2016 |

| USA Release: |

December 16, 2016 (4 theaters in New York and Los Angeles) December 23, 2016 (wide—2,301 theaters) DVD: March 14, 2017 |

living a hard life

relationships between people of different races

racial discrimination

RACISM—What are the consequences of racial prejudice and false beliefs about the origin of races? Answer

ex-soldiers with war injuries and noticeable psychological damage

coming to terms with key events in one’s life

bitterness

SEXUAL LUST—What does the Bible say about it? Answer

PURITY—Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Denzel Washington … Troy Viola Davis … Rose Mykelti Williamson … Gabriel Theresa Cook … Parade Participant Jovan Adepo … Cory Stephen Henderson … Bono Russell Hornsby … Lyons Saniyya Sidney … Raynell Toussaint Raphael Abessolo … Troy's Father See all » |

| Director |

|

Denzel Washington |

| Producer |

|

Bron Studios MACRO See all » |

| Distributor |

August Wilson’s play “Fences” premiered in New York in 1987. Arguably Wilson’s best (I prefer his “Jitney,” which is now being revived on Broadway), “Fences” won the Pulitzer Prize and the Tony Award for best drama. The play was successfully revived in 2010, with Denzel Washington and Viola Davis renewing the roles originated by James Earl Jones and Mary Alice.

In the 2016 film version, Wilson, who died in 2005, is given full credit for the screenplay. Wilson insisted that his adaptation be directed by an African American. That is one reason, perhaps the most significant one, that the film took so long to reach the screen.

Denzel Washington directs, as well as stars in, the film. He gives a powerful performance, but not a great one. I did not see Washington play the lead on Broadway, but I did see James Earl Jones play the part thirty years ago. I was stunned by that performance. I still remember Jones’ characterizations: his strained gait, his rich baritone voice, and even his clenched batter’s face—a visage of a man who thinks of himself as being at bat every moment of his life. Jones broke through not just the play’s scenery of a run down house and an unfinished backyard, but the whole proscenium of the 46th Street Theater (now the Richard Roger’s Theater). Jones bore into the material, and into the audience, in a way that only a great stage actor can.

Washington starts off well. He is forceful and precise. His delivery pounds as much as it cuts, and there are times when he comes across as eloquent and full of pathos. He can express pain and remorse even in the way he breathes. But as the film moves forward, he holds onto the ball too long when he should have thrown or even dropped it. His portrayal becomes fragmented, and the film loses its shape.

I realize that the goal in making a movie is to add two and two and come up with five, but the film version of “Fences” falls short of even 3 and a half. The long speeches, the endless baseball metaphors (“death ain’t nothin’ but a fastball on the outside corner”), and the plot-serving presence of a brain damaged character (a staple in Wilson dramas) make for moving interludes, but they too often detract from a long film that could have used some paring down. This game’s innings stretched on way too long.

I don’t blame Washington, the actor, as much as I blame Washington, the director. Didn’t they talk to each other on the set? The director does not open up what is admittedly a limited visual space. Washington’s filmmaking technique is leaden, and more confining than the story’s actual setting. Even worse, he gives himself too much of the screen time, and almost mutes his supporting cast. Sometimes, he acts as though he is still walking the stage boards and striving to be heard in the balcony.

The other characters, played by a fine supporting cast, too often register merely as appendages to Washington. Their characters, although interesting, never take flight. Even Viola Davis, an extraordinary actress, especially in small parts, seems lost. She should be a kind of cleansing rain, but she comes across as a light shower, next to the Washington hurricane.

It is difficult to take a play, especially a classic one such as “Fences,” and make a successful movie out of it. Sometimes the confines of a stage set are as important to the story as the characters themselves. The end of the road tenement in “A Streetcar Named Desire” and the forgotten dive bar in “The Iceman Cometh” speak of last chances long gone. The backyard, with its unfinished fence, in Wilson’s play gives the same sense of having reached the end of a journey, usually a failed journey. It’s not that there’s a better horizon down the road or over the hill; it’s that the road has come to an end, and the sun has risen and set for the last time. The camera can take a viewer beyond the cramped space and beyond the roadblock. The question remains: was it ever supposed to?

“Fences” takes place in Pittsburgh in the 1950s. Troy Maxson (Washington) is a sanitation worker who had dreams of becoming a professional basketball player. He missed his chance, because the leagues did not admit blacks when he was in his prime. When blacks were finally allowed to play in the major leagues, Troy’s time had passed. He is bitter about the missed opportunity, and he takes his ire out on his friends, his wife, Rose (Davis), and especially his son, Cory (Jovan Adepo), who has his own dreams about playing college football. Throughout the course of the drama, family secrets are exposed, hostilities surface, relationships fracture, and redemption calls. “Fences” addresses issues of good and evil and whether man is ultimately redeemable, even in the most wretched of circumstances.

Troy drives a sanitation truck. He is the first black man that the company allowed to be a driver. But Troy will always see himself as a baseball player who is forever in the batter’s box. Troy’s adversaries are many, but the one he sees standing on the pitcher’s mound most often is the devil. Rose tells Troy: “Everything you don’t understand you call the devil.” In his own way, Troy understands the prince of lies all too well. Whether it is racism or temptation to sin (he refers to his own adultery as a moment when he couldn’t resist stealing second base) or even a furniture salesman, Troy suspects that evil is a living and breathing entity that exists in many forms in many places. Troy may be surrounded by dreamers and may be a bit of one himself, but he is also a realist.

There are many memorable dramatic moments, some great writing—some of the best passages ever written by an American—and many Biblical references in the film. For those reasons, I still recommend “Fences.” The play will survive as a chapter of American history, a part of our country’s landscape and a piece of our national poetry.

August Wilson is a great American playwright, and although the movie adaptation of “Fences” is not up to the standards of the original play, I believe it is well worth a viewing. Most of the great American plays by O’Neill and Williams and Miller have been made into mediocre movies, but if the movie version is all we’ve got, I say take the morsel instead of an empty plate.

Violence: Mild / Profanity: Moderate—“God d*mn,” “good G*d,” “Lord,” “Godforsaken,” “d*mn,” “h*ll,” “a**,” s-words / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 3