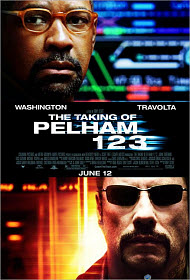

The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3

for violence and pervasive language.

for violence and pervasive language.

Reviewed by: Sara Bickley

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Action Thriller Remake |

| Length: | 1 hr. 46 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

June 12, 2009 (wide—3,000+ theaters) DVD: November 3, 2009 |

FEAR, Anxiety and Worry… What does the Bible say? Answer

Thieves in the Bible: Theft, Robbery, The two thieves

About murder

Original sin—Fall of man to sin

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

VIOLENCE—How does viewing violence in movies affect families? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Denzel Washington John Travolta Luis Guzmán (Luis Guzman) John Turturro James Gandolfini Victor Gojcaj See all » |

| Director |

|

Tony Scott |

| Producer |

|

Scott Free Productions Tony Scott Columbia Pictures See all » |

| Distributor |

“The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3” is a film of both style and substance. Alas, the two are at odds; style ultimately dominates, leaving substance unexplored.

The initial premise is similar to Joseph Sargent’s 1974 version of the story: hijackers take over a car of the titular New York subway train, demanding money. If they are not paid within an hour, they will begin killing passengers. To complicate matters, the leader, known as “Ryder” (played by John Travolta) will only communicate with one person, a subway dispatcher named Garber (Denzel Washington). Garber, under the watchful eyes of his colleagues and the police, maintains close contact with Ryder. His goal is twofold: to stall the criminals until the money can be collected, and to tease out information that might lead to their capture.

The 2009 Pelham distinguishes itself from its predecessor by expanding the characterizations of both men. The original Garber was an unpleasant man, but in small ways. He was brusque to the point of obnoxiousness, but his ethics were never called into question. The remake reverses this: Washington’s Garber is a personable family man, but is haunted by accusations of serious misconduct. This characterization is wholly successful, and, late in the film, it effects salutary changes to the plot.

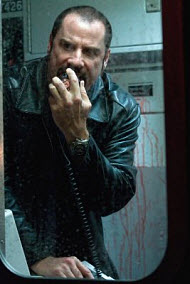

The embellishment of Ryder is less pointed and less meaningful. “Mr. Blue,” the equivalent character in the 1974 film, was a fascinating paradox: a venal, disillusioned man, but also coolheaded and totally in control of the conversation. Ryder is both a darker and a weaker character—he is always on the edge of losing control, but this does not make him more menacing, only more pitiable.

In a more interesting development, Ryder is also given an edge of spiritual evil. He is explicitly identified as coming from a Catholic background, and there are suggestions that he still identifies with the faith (he wears an earring in the shape of a Roman cross). But he seems to have accepted only half the gospel. He believes in original sin, but not in redemption, and invokes humanity’s fallen state to disclaim responsibility for his own actions. He is openly contemptuous of God.

Because of this, the film ultimately hinges on a conflict of worldviews: despair versus hope, Ryder’s stunted half-Christianity versus Garber’s non-sectarian optimism.

“We all owe God a death,” says Ryder. He has ruined his own life, and sees no future but death.

“We each owe God a life,” responds Garber, who has also done wrong and suffered for it, but still hopes to redeem himself.

There is no question of who the audience is supposed to side with: Ryder is presented as physically, culturally, and morally repulsive, and Garber’s hope for the future is seen as courageous and worthwhile. It’s not the fullness of the Christian message, but it’s refreshingly positive.

That, then, is the substance. But it’s sometimes hard to discern under the clamor of the film’s style. Director Tony Scott uses all the devices of trendy freneticity: hasty camera movements, fast cutting, rapid alternations of slow and fast motion, and a disorienting reliance on aspect montage. This exhausting mix is complemented by random references to ‘70s cinema: the title sequence is retro, the last shot is a freeze-frame, and, in between, the film works in a visual quote from “The French Connection” and gives the hijackers costumes and hairstyles that seem more period than contemporary.

The script takes every opportunity to inject drama, and frequently botches it. There are two car crashes, although the plot does not require even one. A pair of bit characters are gunned down in a welter of overcranked gore that Peckinpah would’ve found excessive. The score is distracting: a constant barrage of beats and whooshes that erases any distinction between tense and quiet scenes.

The dialogue is plausible and frequently witty, but it is also annoyingly unfocused. One exchange borders on ludicrous: Garber, about to go into a hazardous situation, is on the phone with his wife. She tells him to pick up a gallon of milk on his way home. So far, so good; this is believable as a woman trying to keep a sense of normalcy under stressful circumstances. But then… Garber asks if a half gallon would be sufficient. The mood is destroyed. That line may have been intended as gallows humor, or as an attempt to distract himself from danger by replicating an ordinary, “comfortable” marital squabble, but it doesn’t sound that way. It sounds as though he really cares about the milk.

The loose, rambling feel of the dialogue is especially unfortunate; it, as much as the overwrought visuals, detracts from the clash of personalities and worldviews at the heart of the film.

Offensive Content

The script contains a great deal of vulgarity, including upwards of sixty sexually-derived expletives, about ten scatological terms (several of which occur during an extended anecdote about defecation), and a number of milder offensive terms, including repetition of the ethnic slur “greaseball.” Vulgar visuals include three obscene gestures and a shot of a child urinating.

In addition to Ryder’s continual mockery of God, there are about five instances of incidental profanity.

Sexual content is fairly minimal. A woman briefly flashes her bra on a Webcam, but this not played for titillation; it is simply shorthand to establish her relationship with another character. The dialogue includes a few sexual references amidst the general texture of vulgarity, including jocular mentions of adultery and prison rape.

Violence is central to the story. A number of fatal shootings (malicious, accidental, and in self-defense) are shown; most of them are bloody and explicit. Shots are fired to intimidate, and, at one point, passengers are trapped within the speeding train, which threatens to derail.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Extreme / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Now, as a Christian I looked what the sexual content of this movie was online before I rented it (because that is the most offensive to me and won’t see a movie tainted with a bunch of sexual sin) And what I found was just a flash of some cleavage. So as far as that goes there really is no sexual content. However, you have to check with you spirit if God wants you to see the movie if it is going to cause you to stumble due to the 100 f and mf-words. In my opinion if you watch movies like this all the time maybe you need a break from the languange but otherwise I thought it was fine and wouldn’t nor didn’t cause me to stumble there is some violence but that’s a given in this type of movie and isn’t horrific over all A very well done movie!

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

It really was a stupid movie, had no meaning and the only thing I got from it was I wish I would have researched it more because that was 2 hours of my life I will never get back! What a waste of time. That teaches me to who I listen to get advice about movies. The same person that saw two movies I didn’t like told me it was great. That is something else I learned, watch your source of who is telling you to watch a certain movie.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1

Yeah I can handle an occasional f-word, even SOB, S if it’s realistic. Preferably though PG-13 is the only thing watchable anymore because the R rated movies have just gotten worse and worse. But people don’t even talk this way in real life. Every person in the movies uses wall-to-wall profanity. Writers are just plain idiots who write their movies like this.

It ruined any chance the movie had for me, it makes me think of Bruce Willis last Die Hard movie that released as PG-13. All the other Die Hards, except for the first one, were profanity laced throughout. The last Die Hard was watchable and a good action picture. It made great money and movie makers should learn their lesson, because younger teenagers want to be able to see these movies, and they make up BIG BOX OFFICE!

My Ratings: Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½