Watchmen

for strong graphic violence, sexuality, nudity and language.

for strong graphic violence, sexuality, nudity and language.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Extremely Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Sci-Fi Action Mystery Thriller |

| Length: | 2 hr. 43 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

March 6, 2009 (wide—3,500 theaters) |

Watches and watchings in the Bible

About murder in the Bible

What is the Biblical perspective on war? Answer

NUDITY—Why are humans supposed to wear clothes? Answer

VIOLENCE—How does viewing violence in movies affect families? Answer

How can we know there’s a God? Answer

What if the cosmos is all that there is? Answer

If God made everything, who made God? Answer

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Jeffrey Dean Morgan (Edward Blake/The Comedian) Malin Akerman (Laurie Juspeczyk/Silk Spectre II) Carla Gugino (Sally Jupiter/Silk Spectre) Patrick Wilson (Dan Dreiberg/Nite Owl II) Billy Crudup Jackie Earle Haley Matthew Goode See all » |

| Director |

|

Zack Snyder |

| Producer |

| Warner Bros. Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Legendary Pictures, Lawrence Gordon Productions, DC Comics, See all » |

| Distributor |

“Justice is coming to all of us. No matter what we do.”

For conservative Christian audiences, the prospect of seeing Zack Snyder’s “Watchmen” is a non-starter. There is male frontal nudity (albeit blue and animated); numerous instances of blasphemy; shots of women’s breasts; gory violence; and a nude love-making scene. I suspect that (with the exception of Dr. Manhattan’s nudity) such content is put in there for the fanboys, because it doesn’t contribute to the story or to the film as an aesthetic pleasure.

However, those caveats aside, let me state at the outset that “Watchmen” is a serious work of art. Calling the synthesis of comics and ideas “serious art” seems oxymoronic, but it is not. Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” is serious in a way that most comics are not, for the simple reason that it contains commentary on the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the prospect of nuclear destruction, quantum physics, the peace movement, social issues such as drugs and crime, and the philosophical significance of power and the use of violence. This seriousness is compelling, but, in its specifics, it is also the Achilles heel of the film, because all the references are so dated. This kind of newspaper topicality is what Robert Frost avoided in his poetry, saying, for example: “Eliot has written in the throes of getting religion and foreswearing a world gone bad with war. That seems deep.” That seems deep. The killing irony is that there is no news worse than old news. Who cares about World War I now? That is why Frost is read and enjoyed by more undergraduates than Eliot or Pound is. Frost’s depth is metaphysical, not political.

This is Watchmen’s great virtue as well. Although it is a relentlessly political commentary and anti-conservative, that is the weakest aspect of the work. The strongest aspect is the character of Dr. Manhattan who provides a profound metaphysical dimension around which the temporal issues orbit like planets around the sun. Arguably, without that character, “Watchmen” would be a very good comic book series, but not the classic that it is. The other problem with the movie, besides the topicality of faded 1960s issues, is the disjointed narrative style that it faithfully copies from the comic book. There are intermittent flashbacks that jump from 1940 to 1959 to 1965 to 1985 and points in between. This makes it difficult to follow, if you haven’t read the graphic novel. Preferably, twice.

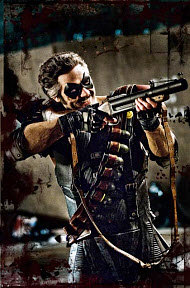

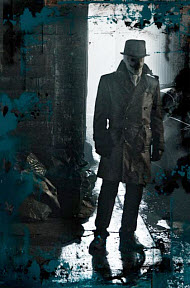

For those not familiar with it, the novel charts the rise of heroes in the United States from the 1940s. These heroes are roughly analogous to American military power and the strengths of its civil society. Dr. Manhattan represents the advent of the nuclear age and the advantage the United States holds over the rest of the world. The retelling of the past (known as “alternate history” in genre terms) occurs in 1985, in the journal of Rorschach, one of the heroes. In addition to him and Dr. Manhattan, there is Nite Owl, the Comedian, the Silk Spectre II, and Ozymandias. The movie opens with the death of one of the characters and the suspicion that someone is out to kill all of them. This, as illustrator Dave Gibbons describes in numerous interviews, is the Hitchcockian “macguffin,” the pretense of the plot. But the movie is about character and ideas, not plot.

Rorschach takes us on a picturesque tour of history through his investigations in space and time. In 1977, the Keene Act outlawed the heroes, and those who didn’t go insane or weren’t killed were forced to retire. Nixon is into his third term, the United States won the Vietnam War, and the Soviets are threatening a nuclear war. That is the social background of the novel.

Equally compelling to the metaphysical and political elements are the emotional issues. The characters are fully fleshed-out in their relationships to one another, their histories together, their resentments and friendships, and in that sense the novel is epic in scope, traversing all boundaries. The affairs between the characters are convincing and felt: the pains are real, the pleasures are real, the human issues which separate them are real. Compared to “Watchmen,” the “X-Men” movies are adolescent exercises in adult conversation, and don’t get me started on the infantile level of “Star Wars.” “Watchmen” is a film for adult tastes and sensibilities.

Violence as an expression of power is central to the understanding of the movie and the characters. In an interview, Alan Moore stated, “And yes, Watchmen came to be about power. About power and about the idea of the superman manifest within society.” The idea of a Nitzschean “superman” is perfect for the conception of a superhero. Similarly, power and the “superman” is what “The Dark Knight” is about as well. In that film, power is wielded by criminal gangs, by the police, by Batman, and by the Joker. Each of them has a different ethic in their use of violence. The police are deontological, placing the law above all other considerations. The criminal gangs and corrupt police officers are utilitarians: whatever action benefits them the most is the best action. Batman operates on virtue theory: the action must be “right” because it is intrinsically the right thing to do, whether it is legal (deontological) in the eyes of the law or beneficial (utilitarian) to him doesn’t matter. The Joker is non-ethical. He is the supreme nihilist and doesn’t even recognize a value system with “good” or “bad” as descriptors. Seen from this perspective, societal conflict is a conflict of value systems and force.

“Watchmen” is similar to “The Dark Knight” in that way. There are power constituencies (the military, the police, the heroes, the Russians, etc.), all of whom use force in accordance with their ethics. Moore stated in another interview, “We tried to set up four or five radically opposing ways of seeing the world and let the readers figure it out for themselves; let them make a moral decision for once in their miserable lives!” It is important to know that Moore is a self-proclaimed anarchist. Anarchism as a system of thought is a radical left ideology which is anti-authoritarian. This is why in Moore’s “V for Vendetta” and in “Watchmen” there are characters who wish to recreate a new order by first destroying an existing order, as in the prison riot. Toward that end, Moore gives us moral “choices” on the philosophical use of violence.

Those moral choices are represented by the kind of “hero” we identify with. Rorschach is described as a psychopath, but in fact he is the movie’s legalist, the deontologist who adheres ruthlessly to the strict letter of the law. The Comedian is perhaps a hedonist, doing only that which gives him pleasure, though it may not be “good” for him. Nite Owl, like his doppelganger, Batman, is an aretaic; he wants to do the right thing in any given situation, as does Silk Specter, although that sometimes means crossing the law. Ozymandias is a utilitarian, willing to sacrifice some to save many. And Dr. Manhattan is the ultimate existential materialist: he exists in Time, not Space, and sees life itself as matter. At one point, he argues that a dead body has the same amount of matter as the living one, and he speculates what benefit life is to the universe.

Also, like “The Dark Knight,” the movie takes its violence seriously. Force exists as an ethical statement—punitive, pleasurable, beneficial, destructive—and not as a gratuitous exercise of force for the sake of force.

“Watchmen” is a long viewing. It is sometimes ponderous, grisly, and confusing, but for those who have read the book and have reasonable expectations of what can be done in cinematic form, it is an instant classic—a tour de force which asks universal questions through comic book characters. For Christians, Dr. Manhattan represents the seeker who questions the existence of God and the meaning of life. His questions are in part answered in the realization that life is a miracle, “gold from air,” unexplained by the processes of nature. When the movie is over, the character that viewers will be most interested in is Dr. Manhattan and his journey to another galaxy, a journey he wouldn’t make if he were just interested in matter.

Violence: Extreme / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Extreme

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

*Can mankind become so self-sufficient as to no longer “require” God?

*Is God DEAD?…

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

On to the potentially content. This is a Christian site, after all, so that is why everyone comes on here in the first place. First of all:

Don’t bring your kids. It’s rated R. In the UK, it’s rated 18. The MPA reason starts out with “strong bloody violence.” Any parental guide on the internet (and there are quite a few) will list for you every single act of violence, sex, language, drug use, and thematic material. If you brings your kids into the theater after that, and you end up wishing you hadn’t, it’s your own fault.

The violence is by far the most “offensive” element to this film. The characters in this film are hardened men and women who have seen the worst parts of humanity and in the process have lost some of their own. We see the world through their eyes--and a very violent world it is, too. Bones breaking, a meat cleaver smashed into the forehead multiple times, bodies exploding, arms being sawn off… you get the point. It is violent. That being said, if you can handle that, fine.

Many people on here have complained about the sex and nudity. Yes, it is graphic. But it is not pointless, as some are suggesting. The whole point of Dan and Laurie’s sex scene is that when he’s only Dan, he feels impotent, but when he’s dressed up as Nite Owl, he feels powerful. It shows how strongly he’s connected to his alternate identity and to saving the world. As for Dr. Manhattan’s full frontal nudity… there is nothing offensive about it. His constant nudity most decidedly NOT in a sexual connotation. He doesn’t wear clothes because he has become so detached from the human race that he no longer cares that he’s exposing himself. In fact, he isn’t really human anymore. So if there’s an issue with lust, it would be rather like lusting after an animal, which is another problem entirely.

COULD the sexual content be cut? I don’t think so. I think it very odd that other reviewers said it could be, while blithely ignoring the fact that the filmmakers could have more easily cut the scene in which Rorschach pours boiling oil all over a fellow prisoner—to me, that’s far more gratuitous than nudity will ever be. But in the case of this film, neither was gratuitous because they were both executed to serve a point.

Some language. Some drug content. Some very nihilistic viewpoints. Many who are “offended” by all this are merely offended that they have to think and come up with their own decision on how to view the cruelties of this world.

In my opinion, God wants us to know about the world we live is so that we can better serve it. If a film includes controversial content in an effort to further our knowledge of the world, I do not consider its content offensive, but merely complex and/or troubling. “Watchmen” is definitely the latter, not the former.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Sadly, I saw several young children in the theater WITH ma and pa. Good gravy folks. Grow up. Watchmen may be a story about heroes—however in the loosest sense—but it is very much suited for an adult audience. This is where the replay value is lacking or rather hurting.

What good is there then in a movie this convoluted? Well, for one, the semi-narrative character known as Rorschach. He’s as bitter as the bitterest of Clint Eastwood’s personas and just as mean ‘n ugly. Rorschach is this outlaw vigilante that roams the city with a burdened conscience and no time for trials and appeals.

Honestly, I think this kind of rash character is sorely lacking in cinema these days. Though rough around the edges, these kinds of guys are nothing more than liberal exaggerations of how men ought to be on occasion. Many stories from the Bible detail the lives of these kinds of men… David, Samson, Gideon, even Jesus… etc. Tempered most of the time, but ready to take up the sword in a moment’s notice. Warriors. Back to the point of this paragraph: the movie is a constant reminder of the corrupt and fallen world we live in.

Yes, we, the audience, in our world. Rorschach cries out a number of times, cries out like the psalmist himself, pleading for hope in a world of destitute lives in and all around him. This make-believe universe the Watchmen live in is a mangled one like ours, and that’s why there’s ambiguity in the characters. Gone are the days of one-dimensional, incorruptible heroes.

The movie even addresses this regression. Miscreants like the comedian commit atrocities under the banner of “good guy” because they realize they can milk the system, for it’s supposedly infallible—largely unperturbed by sporadic defects to the dark side. Without any higher power presiding over these peoples' lives, relativism is rampant. And so the moral conundrums this movie presents actually make for some interesting material. Again, just another dynamic to this extraordinary film.

At the end of the reel, “Watchmen” manages to balance itself. It devotes just as much energy into creating a unique and textured environment rich in effects, choreography, and characters as the film invests in onscreen debauchery and other lewdness. But! For the brilliant meld of life in 1985 with superheroes, “Watchmen” earns its weight in 6 dollar tickets. This is where the director-hopeful in me says yay in the face of the Spirit’s nay, whence the battle of pros vs. cons in this film. Hmm… another conundrum.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Reality is not sunshine and flowers which this movie shows. Christians frequently live in an almost illusionary view of human society. Violence and suffering are widespread and can be seen everywhere. “Watchmen” helps to show how things really are. A christian should be prepared to face reality not a comforting picture of sanitized morality and society. The Watchmen’s characters reflect certain attitudes and views in life when confronted with hardship and suffering.

As a christian, I highly recommend this movie for one because it is truly a tour de force and two it depicts how power, violence, and suffering can really impact society and ourselves. While it does not depict “clean biblical morals,” neither does anything else in society, and if you simply shut this out how can you go out unto the nations if you don’t see how they actually work?

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

As a Christian, what will we do if superheroes (or men with superpowers) truly exist? Will we condemn them? Judge them as evil or satanic? Just remember what Jesus said about judging.

Matthew 7:1-3 'Do not judge others, and you will not be judged. For you will be treated as you treat others. The standard you use in judging is the standard by which you will be judged.'

Dr. Manhattan is not a god. He doesn’t claim to be one, although his powers are incredibly beyond ordinary, but he’s still a person who has concerns for his fellow men.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

The “Tales” themselves are okay, but I believe the interruptions of the real world into the comic world provide a moment to breathe and think over what has already been seen, before moving on to the next act. This provides greater depth to this film, as well as introducing a little more of the comic into the story.

With that long mantra said, I thoroughly enjoyed “Watchmen.” I really didn’t know what to expect with this movie. All 3 versions are good--but I must faithfully recommend the full blown 215-minute long Ultimate Cut to those fans of the comic and those who enjoyed the first viewing of the film. Wow does it make it better! Like I said above, the added storyline lets the rest of the film sit for a moment, allowing for some breath and thought before advancing with the next section of plot.

With all the praise I can give “Watchmen,” I have to give my warnings to anyone who bothers to read my comment. “Watchmen” is NOT the average comic book film. IT IS NOT FOR ANYONE UNDER 18 AND NOT FOR THE FAINT OF HEART. Okay, now that I’ve got that said, here are my reasons why: the obvious graphic and bloody violence, some breast shots and language. “Watchmen” is an adult’s comic book, and the movie follows suit, its primary audience being adults. It is deep, thoughtful, often graphic in its portrayal of violence and human nature and has mature issues. For those who can stand it, “Watchmen” is an experience in film art. I am still amazed by its breadth and depth. I own and love the comic as well.

The Ultimate Cut is recommended to only hardcore fans--like myself. All three versions are long, the 162-minute theatrical cut seen in theaters, the 186-minute cut on DVD and now the fantastic, fully expanded 215-minute Ultimate Cut. That’s a 3 1/2 hour film!! But “Watchmen” deserves it, and does very well with its elongated running time. “Rorshach’s Journal,” October 12, 1985…

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

The noirish Rohrshack considers his bizarre shape shifting mask as his face, but his real face is an abused and diminished vision of Clint Eastwood. When shown a “Rohrshack” ink blot he recalls being abused by his mother and bullies as a child, and his violent action, and a particularly brutal act of retribution for a particularly brutal crime. Rohrshack recalls deNiro’s “Taxi Driver,” Eastwood’s “Dirty Harry” and to some extent Hannibal Lecter as a vigilante Nietschean Superman of uncompromising violent judgment and retribution.

Rohrschack is the Old Testament God of conservative Christianity judging an unredeemable world. He only receives any sort of caring from Dan/Nite Owl, a combination of Clark Kent and Batman who most resembles the struggles of ordinary people. A few of your commenters posit that an interventionist Christ is the only savior for people in this kind of world. However, this Christ lacks humanity also, unlike the Biblical one.

In the film, there are two Christ-like moments, where Dan/Nite Owl cares for Rohrschack and where the ever distancing Manhattan/Jon is pulled back by Laurie/Silk Specter into human interaction.

A final question is the somewhat unsatisfying denouement, found in many science fiction works, that warring humans will only make peace with each other if faced with a common outside enemy. While a character posits that a “hippie love fest” results, it is not clear why anything like this this has happened, what has changed and why the new common enemy changes the way we react to “enemies” at all. Christians must remember the call is to love your enemies, not replace old ones with new ones.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

First off the positives. If you are a fan of the graphic novel, then you probably will enjoy the adaptation that Zack Synader has made of it. The imagery is beautiful and the CGI is top notch! The movie, like the novel, also sends a message about the state of the country and is very accurate of the times, despite being a movie set in the 80s.

Secondly the negatives. First and foremost to the Parents—DO NOT TAKE YOUR KIDS TO SEE THIS! This movie is adults only so please don’t be deceived that because its a Superhero it is harmless. I don’t know why you would bring them in the first place because the rating CLEARLY states that it IS an R-rated movie. There is EXTREMELY strong violence such as breaking bones, amputation, and very gruesome deaths. There is strong language as well, mostly said by the Comedian, though. There is also a strong amount of graphic sex that, to me could have been left out entirely in the movie and wouldn’t have hurt the story at all. The story, speaking of which, though has a message, is VERY dark and disturbing. Some of the characters, such as the Comedian are very brutal and lack emotion for human well being.

There are many issues of God mentioned in the movie. Dr. Manhattan, despite being almost worshiped by the people as a God says very plainly that his powers, though great, are very limited and he is NOT God. Another Character, Rorschach gives a statement that I found disturbing, but true at the same time. He states something like 'I don’t believe in God, but if he exists, it isn’t he that has messed up the world, its us.'

I wanted to love the movie so much being a fan of the Superhero genre, and this movie has made me want to go read the graphic novel. However, I am also disturbed by the sex and foul language. I like it and dislike at the same time so I’ll neutral on it. When the DVD comes out, you can easily fast forward the sex and foul language parts and not miss the story, so I would probably wait for the DVD, which I’ll probably buy being a fan now of the “Watchmen”. If you are a fan of the “Watchmen” and can handle the violence which though is strong is bearable to me, then wait for the DVD so you can skip the negative parts, because its worth it due to the political message it gives which you can easily match to today.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

As for questionable material: What offended me the most during this movie is the gratuitous amounts of sex scenes and nudity. There were at least three sex scenes, and maybe as many as five. I must admit, during these scenes I had my head turned away, so I can’t tell you how graphic they were, or in which sex actually occurred. In one sex scene, they decided it would be a good choice to use the song “Hallelujah” in the background—something I found incredibly offensive, as it seemed to be glorifying sex (premarital sex, nonetheless). Aside from this, there were other occasions of nudity, one notably being that Dr. Manhattan rarely wears clothes and they were not so kind as to provide any sort of censorship whatsoever. Because of this, I would recommend women not see this movie at all. Also, there is an attempted rape scene that stops before any sex occurs. From other responses I’ve read, some people have an issue with this, but I didn’t have a huge problem with it considering I was just glad they stopped it short.

Also, there is a great amount of graphic violence. In some cases, the violence does not go overboard or is too extreme--but on many other occasions the violence made me turn my head away--and, I’m not a person who tends to get offended by violence. In one case, someone’s arm is broken and you see the bone actually pop out, which was completely unnecessary. The violence in itself, however, would not be something that would have stopped me from seeing this movie.

As for the language that was used: I’m not sure if I remember how bad the language was in this movie, but probably only because I was too busy being taken aback at the unnecessary sex scenes.

Now, onto the moral message communicated by the movie. What I did appreciate about this movie is that it showed a very three-dimensional view of morality. In other comic book movies there tends to be a very cut and dry “good and evil.” However, in this movie you have people such as Adrian who “kills millions to save billions,” the Comedian who seems to be a sellout to the highest bidder, and Rorschach who never compromises “even in the face of Armageddon.” It makes it clear that people’s motives aren’t always so black and white--even though morality is.

Probably the character I related to or agreed with the most (and I know I will be criticized for this) is Rorschach. Although he borders on vengeful and psychopathic, he shows an unswerving dedication to the destruction of evil. What I also appreciate is that when he discusses the evil of this world, he doesn’t shy away from mentioning the gratuitous sex as part of their evil. Rorschach, although cynical, has a very sober view of the world. He also shows a decent amount of insight when he remarks that “God doesn’t make the world this way; we do.” Even though he also shows a negative view of God, he shows a mature understanding of how this world functions in that it is people who are destroying this world. So, while he is a tad over the edge (well--definitely more than a tad), he is the only character who shows a real commitment to good.

Understand that this film does not sugar coat the world, which I do appreciate. I feel like the evils of premarital sex and prostitution are something that we shouldn’t be naive about. However, the depiction of sex onscreen was gratuitous, and could easily have been done without.

That being said, I would probably say that it is all right for more mature viewers to see Watchmen if the sex scenes could be removed. So, if you are 100% bent on seeing this movie, watch it with a friend who has already seen it once it comes out on DVD and skip over the sex scenes. But it would be my absolute recommendation to just avoid seeing this movie altogether--especially if you’re a woman.

In closing: I enjoyed “Watchmen,” but I’m not sure I’d see it again. There are definitely parts I enjoyed from this movie, but I’m not sure it makes up for everything else I had to suffer through.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

And in the absence of God, men created gods of themselves and their ideals. Through science/power (Manhattan), intelligence (ozy), technology (owl), beauty (specter), absolute justice (Rorschach) and anarchy (comedian) . And then we get to watch these gods fail miserably. Even worse, we see the absolute scorn and disdain that these “gods” have for men. Even before this movie, I have often wondered if God saw men like Rorschach did when he said,

“This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown. The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and politicians will look up and shout “save us!” And I’ll look down, and whisper “no.” They had a choice, all of them.

But then I remember that God is love. The movie also takes relative morality to it’s final end—the sacrifice of very many for the rest of us. Rather than God’s sacrifice of himself in Jesus for all of us.

As for the rest of the movie, it takes a strong stomach. But if the atheists and deists were correct (or successful in their propaganda), that’s what the world would look like. Totally depraved.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

I would highly discourage people from going to see the film. After the screening, I was calling my friends to warn them not to go, even though the movie is going to break records this weekend.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

First off, the content. It’s extreme, to say the least. Language is pretty bad, probably somewhere around 20 F-words and GD’s. The thing is, I completely forgot about that for a while after seeing it, because the violence and sex was THAT excessive.

Before I move on, let me explain that I see plenty of rated R movies. Generally, I’m not bothered at all by violence unless it’s in the form of torture, or just excessive for the sake of shock value. So I’m not the hyper-sensitive type that most of us read, laugh, and then promptly ignore.

The violence in this movie is, indeed, over the top, and I rarely ever say that. Dr. Manhattan has supernatural powers that basically allow him to explode people, and you’ll see that in detail. By detail, I mean blood and guts sticking to the ceiling afterwards. There’s a near rape scene which is interrupted before the sex starts, but goes on long enough that the woman is slammed onto the ground, a pool table, punched several times, and at the end is quite bloody. Later, we see Rorschach in one of the movie’s MANY flashbacks, remembering when he crossed the line into brutality. He was searching for a man who kidnapped a young girl. He enters the house and finds her clothes hidden in a fireplace. He later looks outside and sees the man’s two dogs fighting over a bone with a little shoe on it, obviously being the dead girl. The man later comes in and he chains him up. The man admits he killed the girl, then fed her to the dogs, and claims he has a problem and just needs help(at least Snyder seems to realize this current claim in society is a load of crap). Rorschach disagrees and buries a meat cleaver into his head, and in extreme anger, does it several more times to the dead man.

Later, Rorschach is about to be attacked in prison while in the food line. He sees it coming, knocks his attacker to the ground, and pours steaming hot cooking oil on the other prisoner’s face. Unfortunately, we see the man screaming for several seconds as the acid burns him. Later in the prison, a man wanting to kill Rorschach reaches into his cell in anger. Rorschach grabs his arms, breaks a few fingers, and ties his arms up with a cloth so he couldn’t get them out. The man’s “friend” then orders his other “friend” to get him out of the way, saying it’s nothing personal. His method of getting him out of the way is using the electric saw that he was going to use to cut through the bars to get to Rorschach. He cuts through his arms, and it’s actually bloodier and more shocking than it sounds like it would be. By the way, the guy could have easily cut through the bars on the other side, since Rorschach’s cell was quite wide. This is what I mean when I say excessive violence… there’s often no point whatsoever other than to shock the audience, which makes it somewhat similar to the “horror” movies of today.

Sex-wise, there’s a large amount of that, too. There are three sex scenes that I can think of. The first involves Dr. Manhattan cloning himself to have sex with Silk Spectre while he works on something. It’s supposed to be funny. The second involves Manhattan before he was a superhero, having sex with his girlfriend. It’s short, fortunately. The third is a ridiculous scene between Nite Owl and Silk Spectre, which felt like it was at least a minute long. I looked away on this one(and the other two) so I can’t tell you exactly how graphic it was, but from what I hear it’s quite graphic with lots of nudity. There are also several other short scenes, such as Nite Owl and Silk Spectre almost having sex(apparently it was cut short because he’s only turned on when she’s initially dressed as a superhero), his dream where they “unzip” their naked bodies to reveal themselves clothed as superheroes, a stripper outside tries to tempt Rorschach by revealing her breasts, and Ozy’s many TVs include one which looked like a porno. Oh, and Manhattan seems to prefer not being clothed, as he’s naked for more than half of his time onscreen.

For those thinking “well, that’s a lot of stuff, but I can overlook it if the movie itself is really good.” Unlike movies like The Departed or “American Gangster,” this movie does not fall under the “really good” category. The first 3/4ths of the movie involve backtracking, and a LOT of it. You get numerous glimpses into the past of the movie’s many characters, which might seem like a good thing, but unfortunately the plot of the movie is lost in the character development. There is little to no structure in the movie, due to the fact that more than half of it is exploring the pasts of various characters. If you’ve read the novel, it will be less confusing, but a movie should be able to stand alone, rather than forcing its viewers to read the book first.

Another way in which the book is much better are the parallels to reality. During the entire movie, you have this lingering feeling that there are messages that are supposed to represent current trends in society, but are somehow lost in translation. The reason for this is that Snyder failed to adapt the parallels from the book into modern issues, and the result is a couple of references to nationalism and little else.

Finally, there are really no redeeming values. All of the characters are very human, as superheroes, if they existed, probably would be. What are the odds that everyone would be squeaky clean like Peter Parker? While this insight is certainly an interesting one, “Watchmen” takes it to an extreme. The Comedian quickly makes you feel no remorse whatsoever for his death, as you see he was a rapist, a womanizer, and generally enjoyed murdering people. Rorschach is not afraid to use any means necessary to exact justice. Silk Spectre is desperate for love in all the wrong places, following her mother’s footsteps. Ozy is essentially obsessed with himself, and has a very twisted view of liberating humanity. Dr. Manhattan is generally without emotion, and in reality hardly human at all. Nite Owl is the closest thing you’ll get to finding a 'good guy', and seems to be the only one who enjoys helping people at all.

In conclusion, the violence and sex is excessive, and the movie is poorly made. Even most fanboys will likely forget about it quickly, and eventually look back and realize it pales in comparison to the novel. Quite simply, the movie has nothing that makes it worth watching, and plenty that makes it worth avoiding.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2½

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1½

Overall, the movie was very offensive and sinful. I felt like the movie had a message that you can be a hero and still do REALLY bad things like fornication, rape, take the Lord’s name in vain, etc. It was like they were saying that everyone does bad things and as long as you do some things good it’s ok. “All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God,” and “The wages of sin is death.” the Bible says. We are not saved by good works, but by the sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross (to all who confess Him as Lord).

I really like superhero movies and couldn’t find out too much about the movie before I went or I wouldn’t have gone. Adults and kids beware and do not go see this movie if you proclaim Jesus Christ as your God.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

If you’re into gore, mixed with soft core porn, and a weak story line that tries to be philosophical (but fails on so many levels) then this is your movie. I went into this movie with high expectations. I loved “300” for it’s breakthroughs in film technique and picture style. The violence in “300” was palatable to me, because it was done with comic book like textures and colors. Intelligent viewers understood what we were seeing and didn’t need it to be spelled out for us. The textures in “300” were completely void in “Watchmen.” It is in-your-face up-close-and-personal.

To say the violence, gore, and sex is “graphic” is an understatement of HUGE proportions. The previews you see on tv are not even close to showing what this movie is really like.

Parents, please take my advice and do not take your children to this movie. It is a VERY adult movie and not in any way a child’s comic book super hero movie. While you’re at it, you may want to think twice about seeing it yourself. I was thoroughly unimpressed with this movie. I hope the makers of “300” realize that they have done, and can do, much better than what they are currently offering moviegoers with Watchmen. That’s my two cents. Take it for what it’s worth.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2

This movie also endorsed the evil lies about peace on Earth without Jesus, Who is Peace. The Bible is very clear, without Jesus, there can be no peace. He is also Truth. The Anti-christ, is one who will attempt to bring peace on Earth without Truth. We all know Who will win eternally and who will lose forever.

We both had to avert our eyes in numerous scenes. The violence and the graphic crime scene (of the little girl), was just deliberate shock. Thank God, I didn’t see any of it.

This movie is not for any Christian to see. It is beyond the boundary of food sacrificed to idols. It is filth to eat and drink and filthy rags into which we dress ourselves.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

I did appreciate one of the characters (two or three different times) mention that God is not the reason why bad things happen, but that we (humans) are responsible for the bad things we bring about.

That blue guy you saw in the trailers is naked the entire time and yes, shots of his lower region are always there unimpeded. This is not the superhero movie most will expect and it was way too long (2:40).

I humbly disagree with those who find this movie positive from any Christian point of view. I simply wish I didn’t see. Save yourself $10 and disappointment.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

^^^This statement in itself is not only “politically incorrect,” but also qualifies me as a “terrorist” in some the states (such as Missouri). I suppose Mel Gibson is also one after directing “The Passion of the Christ.” If religious messages are not allowed in main-stream media, that’s one thing. But how is it then, that it is NOT politically incorrect to portray Dr. Manhattan (who no more is a big-screen metaphor for the New Age “christ” Matreaya, with his 'third eye opened') as being God? Or what about all the other 'watchmen'? It’s one thing to have human flaws, but I was hard-pressed to find a redeeming quality in ANY of these characters, each of whom seems to represent a different form of debauchery (rape, greed, murder, adultery, etc.).

Did anyone else notice that this movie seemed to push a prospective one-world government, AKA “New World Order,” as being the only peaceful solution in a war-ridden world? Read Revelation… JESUS is the only peaceful solution; a one-world government will only usher in a tyrannical dictator unsurpassed by any figure in history.

If any of you think that the elitists in control of Hollywood are not directly measuring the population’s sensitivity with this movie release, think again… After all, it’s been done in the past.

I’m a Christian, not a prude. I used to own the movie “Superbad,” so obviously I can tolerate raw humor and a bare breast here and there (after all, I’m human—not perfect). But I have never felt so utterly AGHAST at the cinemas as I was when the main character finds the butchered remains of a little girl. My husband and I just had our first baby--a girl--and, as parents who DON’T bury their heads in the sand, we are MORE than aware of all the evil in this world that would love to ensnare her… but that does NOT mean we want to pay good money to watch a dog chew on a child’s bloody leg bone---little black shoe still attached and all. I do my own research in order to be prepared for the kind of evil I’m up against as a parent and a citizen of Earth, I don’t need a graphic, DEPRAVED movie to “inform” me, especially when its astronomical budget was no doubt financed by elitists who have their OWN agendas (including, but not limited to, measuring how desensitized we are).

We sent them a clear message by leaving during one (of the countless) blue-flacid-penis scenes. (Unfortunately, 2 hours of each of our lives had already been wasted at that point). See, men and women in the military have to go through “desensitivity training” before battle. Doesn’t that seem eerily close to something we’re being subjected to nowadays? Still, a bigger question remains… WHY????? (These answers and more can be found in Revelation.)

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

You see people’s arms being sawed off, an ax going into someone’s head, dogs ripping apart pieces of a little girl, a guy falling out a window, it’s gratuitous and really stomach-churning violence. I felt it sent the wrong message on all levels.

I also hated the sex of this movie. It was all fornication and the rape scene was really hard to watch. I felt it was watching a porn movie and that it portrays society’s “if it feels good do it” attitude. There were about five sex scenes, which is ridiculous! I can’t believe the music they played during one scene. Gross, disturbing, and disgusting.

I also hated the length. I thought this movie was over, and then it kept going! The only positive thing was it made me consider how awful nuclear war would be.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1

I found some of the scenes extremely offensive and obscene in their brutality and violence. If you enjoy action movies then you will enjoy the scenes in which the heroes powerfully and deftly take apart the enemies, and each other and although the characters are supposed to be “normal” people they are obviously possessed of a strength far greater than that of regular joe. I guess that if your a sci-fi fan then you will enjoy the antics of Dr Manhattan and all that his character entails.

Part of what I enjoyed of the film was its portrayal of the superheroes as real people, not necessarily bound by the constraints of morality that we see in other superhero movies, they are gritty and while they lack the seeming nobility of say Batman, Superman or other comic book creations they are entirely human and therefore given to the plethora of devices that can ensnare us all. They are on no noble quest, and fulfill the role of hero as an extension of their own complex and flawed personalities.

It is one of the best and worst movies that I have seen and I both loved it and was horrified by it. I would not recommend it to a Christian, due to its high level violence, sexual scenes, and language.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 1

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2½

It was extremely bloody. The camera certainly didn’t shy away from gore or death—you see bones break, arteries spatter, arms sawn off. Blood abounded; it’s one of the symbolic and recurring themes throughout both the comic and the movie—like the spot of blood on the smiley face.

There was extreme sexual content. One near-rape scene, another near-sex scene, and then another full, extended, detailed sex scene. I looked away for most of it, but I did get a full-on glimpse of breasts. More than once. And there was no question at all about what was going on. Dr. Manhattan also has no coverage in several shots, though the genitalia was understated and easy to overlook.

The F-word was used several times as well, but the usage was mostly concentrated to specific characters in specific scenes. If on DVD it would be easy to forward through those scenes.

Those would be the major moral issues. The rest of it is largely philosophical and in-depth. Dr. Manhattan, for example, is so god-like, so vastly comprehending that he loses touch with humanity, but later acknowledges that life itself is an incredible miracle, so common it’s easy to lose sight of its precious value.

The Comedian was a super-hero, dedicated to doing good deeds—but he also fails horribly in some moral areas, such as attempt to rape and murder of a woman pregnant with (presumably) his baby. The paradox here is food for thought.

In the end we see the disgusting and sin-filled city eradicated completely. Justice? Perhaps—but it was murder. Injustice? Perhaps—but it was done to save the rest of humanity. What truly is good and what truly is bad? Do you draw the line at impulse, like the Comedian? Do you find your black and white wherever your instinct may lie, like Nite Owl? Or is it so definite, so extreme, it costs you your life—like Rorshach?

The special effects were amazing. I found myself getting lost in the detail in Mr. Manhattan’s eyes. The crumbling of New York was spectacular. The explosion of the bomb was so incredibly real I nearly felt it. The characters were deep, and while the storyline might have been slightly fragmented and scattered, it was still intriguing and thought-provoking.

I recommend this movie only if you are secure in your faith, are unaffected by cursing and ready to look away during the sex scenes. Be prepared to handle extreme amounts of gore, blood, and violence. But also be prepared for a visual thriller, for a philosophical puzzle, for emotion and disgust and passion and horror. It’s a good movie. Watch it if you can handle it.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Having finally seen “Watchmen,” I can honestly say that Snyder still uses the same overblown, self-indulgent gratuitous style used in “300.” Fortunately, the film has an actual story and developed characters that 300 lacked, which make it to where, once and if you can get past the overuse of style, is quite an experience.

The film has the same “comic bookish” in it that “Spider-Man 2” had, no where near “Sin City” but also not at the level of seriousness as “The Dark Knight,” “Watchmen” is somewhere between masterpiece and every other comic book movie we’ve seen. The script (besides dialogue problems) is excellent, staying as close to the original graphic novel as possible. The film starts with the death of the “Comedian” at his apartment, which quickly sets off a string of events all leading to the possible end of the world by nuclear Armageddon. The story follows a set of characters, all retired “superheroes” by way of men and women in suits doing good, only one of them actually has any real superpowers. The film follow these characters from they’re origins in the ‘40’s to where they all arrived in the ‘80’s when the film is set, we get to know these characters as people and psychologically. The film is also set in an alternate reality where America won Vietnam and Nixon is still in power.

As I said, my main problem is Snyder’s direction, the look is right, but the style isn’t, it detracts from the story. But after a while I was able to get past this and became more involved in the story. Some other small problems include the films use of Nixon, which was downright laughable, with the gigantic prop nose and everything about it was simply horrible. There were also some scenes that were downright laughable (mainly the sex scene in the flying machine, which as inappropriate as it was, drove me to tears with laughter). Some of the performances weren’t quite up to snuff either, in my opinion the main performance issue was from Patrick Wilson, who I simply don’t like that well as bad as it sounds. There was also the overuse of ‘80’s music, which was a mixed bag between perfect and just poor.

I do think I’ll see this film again, to try and further my opinions, but like “W.” this film is so hard to review based on simply one viewing, with so many elements that mix and play into each other and play off of each other so importantly, do I recommend the film? Yes. Do I think that its perfect? No, but its closer to “The Dark Knight” than most of the comic book adaptations we are forced to endure nowadays.

Also, the content must be noted. The violence is bloody and gratuitous, over the top and at times quite disgusting. A surefire 10/10 for the violence. The sexual content is also high, there are numerous scenes of nudity throughout, both sexualized and not. The language is not so large of an issue as the others, but before seeing this movie you should be forewarned.

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

The movie offers several characters’ moral viewpoints to the audience, with each person likely to choose a different viewpoint. Are things black and white (Rorshach), shades of gray (Ozymandias), or are morals unimportant (Comedian)? In the end, the characters must make a decision, that will affect the entire world.

Even now, after reflection on the choices offered to them, I am still not certain which choice I would make. I felt the movie kept an unbiased approach to the character’s conflicting moral viewpoints and let audience members CHOOSE what is the right viewpoint (for once). Unlike the reviewer I felt the movie’s political commentary was also unbiased and felt that it wasn’t dated. These issues are as important today as they were in the past. “Who cares about World War I now?” Are you saying because something occurred nearly 100 years ago, it is no longer important? Is what is happening in the present all that matters? By that thinking events like World War II, the Holocaust, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the Manhattan Project, and man landing on the moon are no longer important. These events have shaped what the world is today and very likely what it will be tomorrow. The idea that these events are no longer important sounds like something I would hear from a student failing Social Studies.

The movie does have several sex scenes, nudity and HEAVY violence. In the end however, it did not affect my opinion of the movie. If you can’t handle this, then the movie is not for you. However, if you can, you will find an enjoyable and thought provoking movie.

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4½

Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

I must agree with the other reviewer who has not seen the movie but also commented above. Women do wear offensive clothes and there are many sensual scenes. This could provoke some viewers to have lustful thoughts, and Jesus does say that even if you look at someone lustfully, you’ve all ready committed adultery against your spouse. If you want to watch a superhero movie, just stick with the Batman films (Batman Begins/Dark Knight).

Please use discretion and discernment before seeing this movie. Is there anything in this movie that is true and honorable and right? Is there anything about this movie that is lovely and admirable? I’m just helping fellow Christians make the best choice. So, anyway, I can’t say I would recommend this movie. And I’ve heard from another review site that this movie is extremely frightening and brutal and NOT appropriate for children under the age of 13. Protect your young ones as well.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Extremely Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½