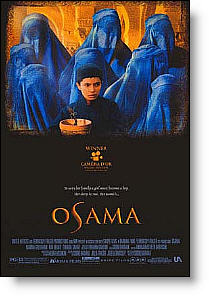

Osama

for mature thematic elements.

for mature thematic elements.

Reviewed by: Jim O’Neill, M.D.

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Good |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Art/Foreign and Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 22 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2004 |

| USA Release: |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Marina Golbahari, Mohamad Nader Khajeh, Zobeydeh Sahar, Mohamad Araf Harat, Zubaida Sahar |

| Director |

|

Siddiq Barmak |

| Producer |

| Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Siddiq Barmak, Julia Fraser, Julie LeBrocquy |

| Distributor |

“Osama,” a film by Afghan director, Siddiq Barmak, tells the story of an Afghani family’s struggle to survive the oppression and abuse inflicted on them by the Taliban government before the regime was overthrown.

Barmak made films for the Afghan Film Organization until the Taliban took over the country in 1996. After the takeover, film and other forms of artistic expression were forbidden, as was the practice of any religion other than Islam. Barmak worked for Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance leader, Ahmed Shah Massoud, making documentary films for the resistance movement, until Massoud was assassinated by the Taliban. “Osama” is Barmak’s first independent film since the country was liberated.

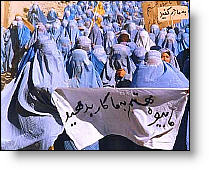

Barmak begins his remarkable film in a rough, documentary style. A large group of women, dressed in sky-blue burkas are protesting in the streets: “We are hungry! Give us work! We are not political!.” The camera gets caught in the melee and gets jostled around a bit. For a few minutes it feels like a Jean Luc Godard or Paul Morrissey film. The demonstration is peaceful and orderly until someone cries: “The Taliban are coming!” The veils conceal the faces, but the fear is palpable, and the disorder soon leads to chaos. Hoses are turned on the protestors, and on the camera. The women who are unable to flee are rounded up at gunpoint and taken to jail.

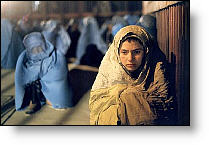

After the demonstration, the camera settles down. Although Siddiq focuses on the hard realities of Afghani life, his scenes lose the grainy, shaky texture and take on a neatly-composed, softly paced and deftly lighted tone. His heroine, Osama, is a 12 year old girl who lives with her mother and her grandmother in Kabul. The city seems to lie under a coat of smoldering dust and ashes. It looks as if the smoke from one bomb has cleared just in time for a new fuse to be lit.

Osama’s father and uncle have both been killed in recent Afghan struggles so she and her female relatives are forced to stay at home. Under Taliban rules, women are not allowed in public unless accompanied by a male relative so if a woman has no husband or other male relative, she risks poverty and starvation.

Osama’s mother is a physician who tries to care for patients in a Kabul hospital. While tending to a patient who is suffering from severe asthma, the ominous cry is heard again: “The Taliban are coming!.” Footsteps are heard in the hall. Doors are knocked on and slammed. Rifles cock. The film uses sound more than visual imagery to convey fear and danger. The violence usually occurs outside the camera’s range (similar to the way violence was depicted in films such as “Slaughterhouse Five” and “Life Is Beautiful”) and as such is all the more brutal and shocking. Osama’s mother quickly hides her stethescope and throws a burka over her head and body. She poses as the asthma patient’s visiting relative. When the patient’s son agrees to take the doctor and her daughter home on his bicycle the Taliban patrol stops him and reprimands him because the woman’s ankle is exposed.

In desperation, Osama’s mother dresses her daughter as a boy and sends her out to work for a shopkeeper. Osama can only carry the disguise so far. Her beautiful face and her graceful feminine movements constantly risk giving her away. One day a group of young boys are taken forcibly from their homes and their workplaces and forced to take lessons in prayer, revolution, dress and bathing from Taliban chieftans. Osama is among the children who are taken away. She maintains her charade for a short time, but the Taliban sentinels ultimately prove too much for her. The pretense, and the girl’s innocence, quickly unravel.

Siddiq has not made an anti-religious film. He does not condemn Islam. He focuses on the social control that the Taliban exerted on the citizens of Afghanistan, and the effect of that control. He gives us a picture of extremism, be it religious or social or political, whose world view places a premium on judgment, retribution and punishment. An emotionally detached, almost bored, mullah lies on a lounge chair amidst his followers and his rubble and passes sentence on the accused of his society.

An adulterous woman in placed in a sac for men and boys to stone to death. A journalist is summarily and publicly shot with an AK-47. A pubescent girl is pardoned on a whim, or as a favor to another mullah. The girl’s life is spared so that she can be sold as a wife to the mullah’s friend, an elderly man who has grown tired of his other wives. The old wives dress and adorn the new wife for her wedding. Her bridal gift is a lock and chain which her new husband lets her choose as if she were picking an engagement ring.

Siddiq’s Kabul is one large sea of lost souls. Osama (played beautifully by Marina Goldbahari, a natural actress whom Siddiq discovered on the steets of Kabul) has a spirit which strives for more, but is no match for a society that is eager to expose sin, but is unwilling to espouse forgiveness.

Christianity sometimes speaks of retribution. “The Book of Revelation” can strike as much fear in our hearts as any Koran passage. But Jesus’ new world order was based on love, especially for the poor and the sick and the abandoned. He died a death which the teachings of the Koran consider undignified and unbecoming for a savior. As Christians, we consider Christ’s self-sacrifice the ultimate act of love. He died on a cross not to expose and condemn us as sinners but to save us from our sins. Over the ages we have acknowledged our sins, and our need to be punished for them, in the Renaissance works of Dante and Milton, in the frontier novels of Nathaniel Hawthorne, and in modern movies such as “Psycho” or “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” The Bible tells us if we turn to God all will be forgiven.

Totalitarian governments don’t look to God. Their charters come out of the devil’s play book and their game never really changes, as we’ve seen year after year and century after century. “Osama” is a poignant and heartbreaking work about the price paid in human suffering for the pride and arrogance of power.

Violence: Moderate | Profanity: None | Sex/Nudity: Minor

Presented in Dari Arabic with English subtitles

[Good/2½]

My Ratings: [Good/4½]