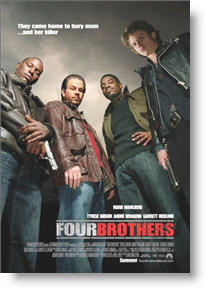

Four Brothers

for strong violence, pervasive language and some sexual content.

for strong violence, pervasive language and some sexual content.

Reviewed by: Kenneth R. Morefield, Ph.D.

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Crime Thriller Action Mystery Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 49 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2005 |

| USA Release: |

August 12, 2005 (wide) |

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Mark Wahlberg (Bobby Mercer) Tyrese Gibson (Angel Mercer) Garrett Hedlund (Jack Mercer) Terrence Howard (Lt. Green) Chiwetel Ejiofor (Victor Sweet) Taraji P. Henson (Camille Mercer) Sofía Vergara (Sofia Vergara, aka Sofi) See all » |

| Director |

|

John Singleton |

| Producer |

|

Di Bonaventura Pictures Lorenzo di Bonaventura See all » |

| Distributor |

“They came home to bury mom …and her killer.”

Plot: The four adopted sons (Mark Wahlberg, Tyrese Gibson, Andre Benjamin, Garrett Hedlund) of a community saint work together to try to discover and punish those who killed her. Rated “R” for action violence, profanity, and sexual situations (including brief nudity and simulated sexual intercourse).

Christians who are sensitive to what is typically called “objectionable content” (language, violence, sex) are advised against going to the film, as it is a hard “R.” The reviewer comments below are focused primarily on thematic issues in this film, since the decision for those who make screening decisions based on objectionable content seems pretty cut and dried.

Warning! There are major plot spoilers in this review.

There is an old clichéd argument when discussing non-violence that says if Mahatmas Ghandi had been born under the rule of Nazi Germany rather than colonial Britain, nobody would have ever heard of him.

This is an argument that suggests for nonviolence to be successful, the evil that one is opposing must be answerable to (politically or spiritually) some higher power that keeps it from simply giving in to the urge to use its momentarily superior power in order to eliminate dissent. It is an argument that Bobby Mercer (Mark Wahlberg) would understand and with which he would probably agree.

When one of Mercer’s brothers suggests that their plan to visit vengeance upon those responsible for killing their mother is contrary to the spirit of her teachings, Bobby shrugs and says, “We can’t all be saints.”

The jarring paradox between the veneration the brothers feel for their mother and the systematic way in which they go about profaning her legacy (in her name) could work—could even be credible—if there were even a glimmer of self-awareness on the part of the brothers (or the film) that the mother’s death is more catalyst than cause, that “she deserves justice” is really just a convenient cover for “I deserve vengeance.”

It might also have worked if the ending of the film were not quite so triumphal in tone and imagery, if the orgy of violence brought about not a release from torment, but a spiritual hangover.

In the climactic scene, two of the brothers confront the man who had ordered their mother murdered. They have arranged for the crew that the man thought would be working for him to turn on him, and it is evident that he will be murdered and his body dumped into the frozen lake. Before this happens, however, Bobby hands his gun to his brother and fights the man in hand to hand combat.

I asked another viewer of the film what would have happened had Bobby lost this fight. Given that we both agreed that Bobby’s brother (or one of the other witnesses) would shoot his adversary at that point, the scene raises some interesting questions. What is at stake in this fight? Is it strictly a dramatic conceit, or does it reveal something about the characters and the audience?

One way of looking at the fight is that vengeance is about the release of anger, and that there is something more satisfying, more primal in physically assaulting the object of one’s anger rather than merely pulling a trigger.

Another explanation, however, is that there seems to be some sort of credibility at stake. Bobby needs to know, and the movie needs us to agree, that he is a better man than the murderer he murders. Better. Not just more powerful. Because there seems to be an almost mythic cultural need at the moment to insist that the source of one’s power comes from something other than merely having the most weapons.

I was surprised (and pleased) that no one in the audience where I screened the film applauded when Bobby and his crew finally dispatched the movie’s villain. Remember when a standard fare of action movies was the “sneer and cheer” dispatch of the villain as Bruce Willis, Mel Gibson, Sylvester Stallone, or Arnold Schwarzenegger finally turned the tables on whoever had been torturing or killing their loved ones and sent him to hell with a “yippee-kay-yeah”?

We live in a different age now, one, perhaps, where audiences have grown weary of the toll that violence takes and suspicious that meeting violence with greater violence doesn’t end violence but only escalate it.

Why then do I give “Four Brothers” a “B”? Because I see it as part of a body of work by John Singleton that explores the question of how individuals or communities can escape or survive violence, especially when the traditional avenues for seeking recourse are either corrupt or simply not available to all members of society.

To say to the victims of violence in “Shaft” or “Boyz in the Hood,” or, especially “Rosewood” that you must not return violence with violence is to say, in effect, you must accept martyrdom.

I give “Four Brothers” a “B” because, even though I don’t think it has the right answer to a complex question (how does one confront evil?), I’m not sure that the film is meant to be taken as the final word.

At the end of Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing” there are two quotes in tension with one another—one from Martin Luther King Jr., the other from Malcolm X. The former preaches non-violent resistance, the latter survival by any means necessary.

Bobby Mercer may be morally compromised at the end of “Four Brothers”, but he is alive. That Bobby can’t quite see that he must bear some of the responsibility for the casualties of his holy war, because of decisions he made before the quest for vengeance became a struggle for survival keeps me from giving the film an “A.” That the film was able to argue—albeit not so convincingly—that his violent justice was a means necessary, rather than a means expedient, makes me rank it slightly above more generic action films.

You won’t mistake Bobby Mercer for Mahatmas Ghandi, but you won’t find him in an unmarked grave, either.

My Grade: B

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Bobby has highlighted a large cross hanging from his neck while walking towards (the camera and) the villain. Would someone who really believes in Christ and his message go out to torture and kill? Some other parts of the story were equally disturbing. One thing that was disturbing was the reaction of the audience.

There were parts, like when the arch villain forced one of his gang to eat food off the floor, that I believe were put in the story to show how bad the leader could be. But I heard about a third of the people in the theater laughing at this episode.

All in all, this is a very violent film. What I thought it would show is different races of brothers come together, which it did somewhat; but the main point it tried to teach is that violent revenge is to be admired, especially if you can get away with it.

Very Offensive/3

Well, “Four Brothers” is not only bad but its laughably bad. The movie actually thinks its being cool but while watching it, you cannot help but make fun of it. The dialogue is so amazingly lame, the characters are so miscast, and the script just downright sucks. I mean in this movie, you have 4 grown men sitting at a table all crying while eating dinner, imagining their their mother is talking to them, then out of nowhere they respond to her as if she could hear them.

Four Brothers is about 4 adopted brothers by this sweet older lady who gets whacked in the beginning of the movie. As the brothers investigate her death they find out there there is more to them that meets the eye. They start causing trouble and eventually find themselves the target of the enemy…

A few things that really stick out is the fact that they are obsessed with homosexual jokes, showing male nudity and making sure all the men are bawling the whole time. …Not only is the dialogue terrible and the script worthless, but the movie actually makes you want to fall asleep in the first 45 minutes. Then when the action happens, you wonder why and how the people are walking around with their guns out in plain daylight in the middle of the street, or where ever they go for that matter. You wonder how they can be in a house riddled with probably 1000 bullets from top to bottom and they can walk out without a scratch. Well enough said …don’t waste your money. …NOT FOR KIDS or TEENS.

Extremely Offensive/1

Now, granted it may not have always been kindly but it was there. These brothers had a bond that showed on and off throughout the whole movie. I don’t recommend this by any means for young children or people that don’t want to hear a lot of cursing and see a lot of killing. Honestly, I hear more at school in one day than in any movie that they could put out on the market. The movie does offer a solid message about brotherhood and that there are good people in the world and sometimes bad things do happen to them.

Very Offensive/3½

The objectional content was language and some vulgar content. Also, somewhere in Romans 12, it says “‘Vengence is mine… I will repay,’ saith the Lord.” The fact that they took matters in their own hands goes against God’s word. The was hardly anything sexual in the movie. Just the scene with Bobby Mercer (Walburg) on the toilet and Jack (Garret Hedlund) in the shower.

There was parts where Jack was accused of being gay. I’ve owned this movie before I was saved. I do not approve of the content, but it has a good story-line. If I had a TV gardian, I would hook it up and use it. But I don’t. If you’re going to be offended by watching it, then don’t. The movie needs to be edited.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5