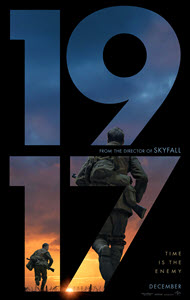

1917

for violence, some disturbing images, and language.

for violence, some disturbing images, and language.

Reviewed by: Keith Rowe

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | War Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 58 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2019 |

| USA Release: |

December 25, 2019 (limited) January 10, 2020 (wide release) DVD: March 24, 2020 |

World War I

Trench warfare

The horrors of war

Heroism

Bravery / courage / self-sacrifice to save others

Willingness to lay down one’s own life for others

Importance of teamwork in overcoming obstacles

Loyalty

Death of brother

What is the FALL OF MAN? Answer

What is the Biblical perspective on war? Answer

War in the Bible

Armies in the Bible

| Featuring |

|---|

|

George MacKay … Lance Corporal Schofield Dean-Charles Chapman … Lance Corporal Blake Mark Strong … Captain Smith Benedict Cumberbatch … Colonel MacKenzie Colin Firth … General Erinmore Andrew Scott … Lieutenant Leslie Richard Madden … Lieutenant Blake Adrian Scarborough … Major Hepburn Daniel Mays … Sergeant Sanders John Hollingworth … Sergeant Guthrie See all » |

| Director |

| Sam Mendes — “Skyfall” (2012), “Spectre” (2015) |

| Producer |

|

Amblin Partners DreamWorks See all » |

| Distributor |

This movie’s serene opening is completely unexpected… two British soldiers are napping in a field in northern France during the height of WWI. Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) is roused by a superior officer and told, “Pick a man. Bring your kit.”

Before Blake’s waking friend, Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay), can protest, the two young men are trudging through a winding labyrinth of trenches. After several minutes of maneuvering down narrow passageways, the soldiers finally arrive at General Erinmore’s (Colin Firth) command bunker.

Erinmore wastes no time in outline Blake and Schofield’s assignment—they are to cross over into enemy territory, rendezvous with a British battalion and deliver a letter which warns of a German trap. Failure to deliver the message will jeopardize 1,600 men, including Blake’s brother. This is one impossible mission even Ethan Hunt wouldn’t accept.

The movie’s premise is simple enough and, barring a few twists along the way, the plot is fairly straightforward, too. But story (Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns wrote the screenplay) isn’t the movie’s strong suit. Even though the film features excellent performances from Chapman, MacKay, Firth, Andrew Scott, Mark Strong and Benedict Cumberbatch, acting isn’t its strong suit either. (Fans of BBC’s “Sherlock” will note that the series’ hero and chief villain are both among this movie’s cast).

So why is “1917” causing such a stir (many top critics have lauded it and it just won Best Motion Picture at the 2020 Golden Globes)? In short, “1917” is a cinematic achievement. Though that phrase is employed far too frequently these days, it’s wholly justified in this case.

For “1917,” director Sam Mendes (“Skyfall”) has attempted the seemingly impossible. Mendes’ original concept, which was inspired by his eight minute sequence at the beginning of “Spectre” (2015), was to film his WWI epic as a single shot in real time. Alas, unlike TVs “24,” the movie doesn’t occur in real time, nor was it shot in order (a few scenes were shot out of sequence). However, the film does achieve the feeling of one long, continuous shot.

This certainly isn’t the first war movie to employ uber-difficult long takes. Many will point to the frenetic, bone-jarring long take in Stanley Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory” (1957)—where Kirk Douglas leads his men on a writhing, weaving course along a bomb blasted battlefield—as the finest of its kind. Others could make a strong case for the extraordinary long takes in “The Longest Day” (1962), “Atonement” (2007) and, of course, “Saving Private Ryan” (1998). While those films featured one significant long take each, “1917” is comprised of a series of extended takes, the longest of which is nine minutes. There’s no overstating the magnitude of what Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins (along with the alchemic editing team) have achieved here.

The film took extensive planning and execution to pull off. The sets were constructed in an almost storyboard fashion. The movie proceeded scene by scene, station to station, and through trenches, mud pits and tunnels. If it rained, the company shut down (but continued to rehearse) until the weather cleared. Conversely, if the previous scene was shot under an overcast sky and the sun peaked through the clouds, they had to wait for the sun to go back in. The sheer logistics of producing such a project (constructing 5,200 feet of trenches, filming in the mud and elements for 65 days, etc.) are mind-boggling and exhausting to consider.

Despite its unqualified brilliance, the movie surely will have its naysayers. Some may feel the movie’s progressive plot and filming technique have detracted from the overall viewing experience, while simultaneously distracting many from realizing that the cause and effect story could’ve been written by a 10-year-old (with all due deference to today’s savvy young people). Others may criticize the movie for being enamored with its own style. All are valid arguments. Normally I grade down for “style over substance” spectacles (like “Dunkirk”), but “1917” is a landmark effort that deserves nothing less than top marks.

Though I could easily spend this entire review discussing the movie’s filming process, I’ll refrain. Since this is a rated R movie, let’s take a closer look at its…

Objectionable Material

Nudity and Sexual Content: Mild. The movie has no nudity. After Blake cuts his hand on a barbed wire fence, Schofield makes an inappropriate remark about masturbation. Though technically not falling under this category, several British soldiers are filmed from behind as they urinate on the side of a building.

Violence and Graphic Content: Heavy. Though “1917” isn’t as violent as many other war movies, it still has its share of graphic scenes. Early in the movie, we see several casualties being conveyed through the cramped trenches on stretchers. None of these shots are overly bloody. Another shot shows soldiers stepping on dead bodies.

Many of the scenes in bombed-out No Man’s Land are stomach-turning. As landmarks to guide them across the muddy and bloody terrain, Blake and Schofield are told to follow the line of dead horses… clouds of flies hover above the fallen steeds. The camera holds a little too long on a dead man trapped inside a roll of barbed wire. We see large rats moving among the corpse-riddled plain. In an improbable scene, a rat trips a wire which causes an explosion that buries a man in rubble.

In a shot that recalls Cary Grant sprinting away from the low-flying crop duster in “North by Northwest” (1959), a crashing German plane rapidly approaches Blake and Schofield, who run straight toward the camera. A German pilot is pulled from the flame engulfed cockpit… his legs are on fire. Schofield suggests they “Put him out of his misery,” which would violate the sixth commandment (Exodus 20:13).

On several occasions, characters are seen running from unseen assailants who are firing at them. In one scene, Schofield exchanges fire with a German sniper and ends up falling down a flight of stairs. After regaining consciousness (the film brilliantly fades to black for a few moments), we see a pool of blood around Schofield’s head. Later, Schofield chokes a German soldier to death. When Schofield swims to a riverbank, we see bloated corpses that have collected against a large fallen tree.

It goes without saying that the climactic engagement, where British soldiers charge the battlefield with bombs exploding all around them, is fairly graphic. Fortunately, because the camera is fixated on a solitary soldier, the scene isn’t overly gory. Far worse are the scenes after the conflict where we see multiple soldiers with bloodied or missing limbs and other assorted injuries.

Vulgarities: Very Heavy. The movie has 15 f-words. It also contains 8 instances of b*stard. There are many other expletives in the movie, including: “J*sus Chr*st,” J*sus (8), “For G*d’s sakes” (2), “Why in God’s name?”, G*d (1), h*ll (6), and sh*t (1). The British swear word “bl**dy” is heard nearly 20 times.

The movie is peppered with other irreverent or inappropriate speech. These words or phrases include: “idiot,” “up yours,” “b*gger out,” “p*ss off,” “w*nking,” and “b*llocks.” There are a couple utterances of “boche,” a derogatory term that referred to German soldiers.

Alcohol: Mild. Soldiers are seen drinking in a few scenes. Mocking the holy sacrament of baptism, one officer christens Blake and Schofield by sprinkling alcohol from a flask onto their backpacks. One soldier offers Schofield a drink from a glass bottle. Schofield says he once traded his medal away to a Frenchman for a bottle of wine.

Drugs: Mild. Several soldiers are seen smoking cigarettes.

Spiritual Aspects

Most war movies contain similar themes, such as bravery, courage and self-sacrifice. In addition to those aspects, “1917” also has several spiritual themes. Early in the movie, Blake and Schofield break bread together, an act symbolic of communion.

Blake and Schofield exhibit excellent teamwork as they work in tandem to overcome the many obstacles thrown in their path. Their training is evident and their dedication to the mission is admirable. As they frequently demonstrate, both are willing to sacrifice everything for the cause. As soldiers in God’s army, Christians are to have the same mindset when it comes to upholding the Great Commission (Matthew 28:16-20).

At one point, Schofield asks Blake why he was chosen for the mission. Though it touches on the doctrine of election, the simple, honest question “Why me?” has been asked by many God followers over the centuries. Like Blake and Schofield, the Bible is replete with unlikely individuals who were chosen for a unique purpose: a stutterer for a spokesman (Moses), a shepherd boy as a king (David), a fisherman as a great evangelist (Peter)? Blake asks Schofield if he wants to go back. Schofield proves his loyalty as a friend and fellow soldier by remaining at Blake’s side.

This degree of loyalty and companionship is reminiscent of Frodo and Sam in “The Lord of the Rings.” Similar to Blake and Schofield’s trek, the Hobbits are required to traverse inhospitable regions filled with untold dangers in order to accomplish their objective. At one point, Schofield tries to pick up Blake, as Sam did with Frodo. As sidekicks, both Sam and Schofield are willing to lay down their own life for their friend (John 15:13-14). Of course, the ultimate example of self-sacrifice is when Christ died on a cross to break the power of sin and redeem humanity (Romans 6:10 NLT).

One of the most human moments in the film is when Schofield seeks refuge in a flat where a French woman is taking care of an orphan baby. The woman tends to Schofield’s head wound. He returns the favor by giving the woman a canteen filled with fresh milk for the baby, which he had gotten earlier at a farm. This act of charity is also an act of providence since Schofield is able to provide precisely what the baby needs. This beautiful scene reveals that the kindness of strangers can exist even in the middle of a war and that we should always show hospitality to others (Hebrews 13:2).

The movie’s villains, the Germans, are rarely seen. However, their destructive handiwork is visible everywhere Blake and Schofield venture (demolished villages, cut phone lines, a valley filled with giant bullet casings, trees chopped down, cows slaughtered with machine guns, etc.).

In a similar manner, though we can’t see Satan, we can observe his malicious works being perpetrated in every corner of the globe every day. Just turn on the nightly news for evidence of this. At this late hour, the world could sure use more people of valor, like Blake and Schofield, to stand up and fight the forces of darkness in this present evil age (Galatians 1:4 NIV).

Final Thoughts

Mendes has achieved a staggering feat of cinematic wizardry with his ambitious one-shot filming. The movie is bolstered by stunning cinematography, astounding production elements, a beautifully restrained score by Thomas Newman and superb performances from its cornucopia of a cast. “1917” is an immersive, visceral and unrelenting journey through claustrophobic trenches, sodden plains and hellish landscapes… with cat-sized rodents and corpses to spare.

“1917” is an unparalleled cinematic achievement unlikely to be outdone in our lifetime. Above all, “1917” has pushed the art forward. For all its flaws, that will be its lasting legacy.

- Violence: Very Heavy

- Profane language: Very Heavy

- Vulgar/Crude language: Very Heavy

- Sex: Minor

- Drugs/Alcohol: Minor

- Nudity: None

- Occult: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Very well done. Morally, language was not as bad as other war movies, and there was actually very little actual war battle’s. Some disturbing and gruesome dead body scenes. I was thinking this movie might even be something my wife or kids could watch if you cut a few images and language.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

The Germans make rare appearances, but their presence is felt everywhere. More than a mortal enemy, they convey a danger that is spiritual as well as corporeal. The devil is at work in everything they do.

I wish I could say that this is a great movie, even a very good one, but it is so derivative(“Touch of Evil,” “Paths of Glory,” “The Longest Day,” “Gallipoli,” “Saving Private Ryan”), and so focused on its own glossy, nimble, even wily technique, that it constantly stumbles. A war movie needs a logical and engrossing plot, one as tactical as the mission it attempts to portray. Many of Mendes” narrative elements make little sense and some defy logic. Such whoppers ensure some exciting cinematic moments, but they lack a point. The two main characters follow a concise road map, but the film’s director seems to have thrown his own map to the wind. He gives us not so much a war drama as a cascading adventure romp. What starts as a search and rescue mission quickly becomes an Indiana Jones roller coaster ride in and out of the rat-infested, always about to cave-in underground tunnels of war-torn France.

I saw two plays in New York this year that Sam Mendes directed: “The Ferryman,” and “The Lehman Trilogy.” Neither was a great play, but Mendes turned both into great theatrical experiences, a rarity these days, on or off Broadway. I wish he could work the same magic in the movies he makes. Those tend to be heavy handed, preachy, and even reactionary. “1917” does not fall into those traps, and it may be his best movie, but its reverence for its own style and image take away from what truly deserves our bended knee: faith and charity, and the courage to live them, especially in the hardest of circumstances.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 3

You know if you read letters of soldiers from the time, you hear mention of their faith. Not in this atheist lens. I sat waiting from beginning to end for the mention of God. Not once. Even “Band of Brothers” had more reference to personal faith and that was set 30 years on. The scene when the soldier leaves the truck, I waited for one person to say God Bless, or for the officer to say Godspeed. Nothing, a few good lucks, that was about it. A faithless paradigm.

The reality of faith’s existence in “1917” was a little different.

“I tell you, he will see that they get justice, and quickly. However, when the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?”—Luke 18:8

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

Moral rating: Very Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 3

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

It deserves Best Picture, Best score, Best Direction, Best Cinematography, Best Sound, and Best Set Decoration.

It had some moral themes and was patriotic and showed men that did their duty honorably. There were soldiers singing a Christian song at the end, but not with Christian zeal. Must see movie. As of today January 14, 2020 it is the number one box office hit.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 5