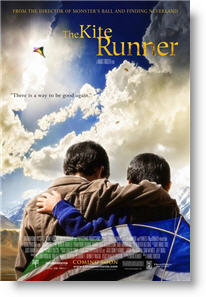

The Kite Runner

for strong thematic material including the sexual assault of a child, violence and brief strong languag.

for strong thematic material including the sexual assault of a child, violence and brief strong languag.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Better than Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 2 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2007 |

| USA Release: |

December 14, 2007 |

| Featuring |

|---|

| Khalid Abdalla, Homayon Ershadi, Zekeria Ebrahimi, Ahmad Khan Mahmidzada, Shaun Toub, Nabi Tanha, Ali Dinesh, Saïd Taghmaoui, Atossa Leoni, Abdul Qadir Farookh, Maimoona Ghizal, Abdul Salam Yusoufzai, Elham Ehsas, Ehsan Aman, Vsevolod Bardashev, Ismail Bashey, Larry Brown, Laurie Burke, L. Peter Callender, James Cotner, Emmy Farese, Susan Farese, Reza Ghasemi, Michael F. Grant, Mason Hsieh, Charles Lewis III, Larry Kitagawa, Nasser Memarzia, Benjamin Miller, Caon Mortenson, Navid Negahban, Henri Ramsey, Salim Razawi, Jeff Redlick, Timothy Roberts, Big Spence, Kelcie Stranahan, Yvonne Truong, Brian Vowell, Zadran Wali, Mohammad Yawary, Susan Zangl |

| Director |

|

Marc Forster |

| Producer |

| William Horberg, Laurie MacDonald, Sam Mendes, Kwame L. Parker, Walter F. Parkes, Mark Sourian, E. Bennett Walsh, Rebecca Yeldham |

| Distributor |

| Paramount Vantage |

“There is a way to be good again.”

“The Kite Runner” is an adaptation of Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling novel of the same name. It is a story which contains sin, remorse, and postponed repentance. It is a tale of a fall but also of redemption. Lastly, it is an account of the destruction and resurrection of a man’s character who is given, in the words of Rahim Khan, “one more chance to be good.”

The movie begins in present day California showing the life of an expatriate Afghani father and son who had escaped the invasion of the Soviets in 1979. Contrasted with their luxurious lives in Kabul, Amir and his father now live humble lives in Fremont making a bare living at the flea markets. Amir graduates from junior college, meets an expatriate Afghani woman, marries her, publishes a novel, and is happy, in spite of the fact that his beloved father, and only relative, later dies of cancer.

One day he receives a call from his father’s friend, Rahim Khan, who is now living in Pakistan. Rahim Khan tells him that he must rescue the son of his boyhood friend, Hassan, from the grips of the Taliban. Hassan is the “kite runner” from Amir’s childhood, a term that is both descriptive of the person who chases after the falling kites as well as a metaphor for sacrificial service. Hassan, as a Shi’a Muslim and ethnic Hazara, is a second-class citizen in Pashtun, Sunni-run Afghanistan. This was true even under the old regime, before the Soviet invasion, but it is especially true of the totalitarian rule of the Wahabi sect of Islam that the Taliban practice.

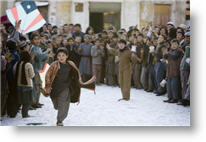

The movie flashes back to Amir and Hassan’s childhood, when they were 10 or 11 years old, and shows their fondness for stories, for flying kites, and for American movies like “The Magnificent Seven” and “Bullit.” Their relationship reaches both its climax and nadir during the annual kite tournament. Amir flies the kite, while Hassan holds the spool and directs him, much as an expert caddy will sometimes direct a professional golfer. As a vanquished kite flutters to the ground, Hassan chases it through the streets of Kabul. A gang of teenage Sunni toughs spot him and decide to pay him back for previously defying them. They catch Hassan and assault him.

This action is the moral crux of the entire story. Amir witnesses the assault and does nothing to help Hassan. The viewer is reminded of his father’s words that “A boy who won’t stand up for himself becomes a man who can’t stand up to anything.” His father is a man who will stand up for a principle, even at the risk of his own life. Hassan, the son of his father’s servant, is also such a person. The contrast between son and servant is striking and tragic. The viewer is able to like Amir, in spite of his fault, because heroism is a quality so rare that we don’t despise people who don’t have it. Heroism is like unconditional love, whose presence in a person is not an indictment of others without it.

Amir’s cowardice eats away at him until it drives him to injustice against Hassan. He tempts Hassan to do things that it is not in Hassan’s character to do. Amir wants Hassan to be guilty of a moral failing, so that he doesn’t feel like such a failure himself. In a final act of characteristic bravery, Hassan takes the guilt of a false accusation upon himself, even though he is innocent. Rather than shaming Amir into telling the truth, this last sacrifice hardens Amir’s heart against Hassan. And that is the last Amir ever sees of Hassan.

As cowardice is the moral heart of the story, the idea of theft as the origin of all sins is the spiritual heart of the story, as Amir’s father explains:

“Now, no matter what the mullah teaches, there is only one sin, only one. And that is theft. Every other sin is a variation of theft. When you kill a man, you his wife’s right to a husband, rob his children of a father. When you tell a lie, you steal someone’s right to the truth. When you cheat, you steal someone’s right to fairness. There is no act more wretched than stealing.”

Amir’s moral theft creates a debt that can be redeemed only by a great sacrifice on his part. In a sense, he has to become a kite runner and retrieve a highly valued trophy. That is why when Rahim Khan calls and tells him “You have one more chance to be good,” Amir knows he must return.

That is the gist of this complicated and beautiful story. The acting by the boys is nuanced and touching. The scenery is convincingly bleak. The terror of the Taliban’s rule strikes a stark contrast between the Kabul of Amir’s childhood and the prison he finds in adulthood. There is nothing morally objectionable in the film, and what violence there is, is a necessary component of the story. The concluding scene contains a joy-filled, redemptive moment when Amir cries out “For you, a thousand times over!” in an echo of his friend Hassan’s words many years before.

“The Kite Runner” is the best and most morally uplifting movie that has appeared on the screen probably since “Luther.” This is the only time I have ever recommended that viewers read the book and see the movie.

Violence: Moderate / Profanity: None / Sex/Nudity: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

The quality of the film was great. The rugged snowcapped mountains of Afghanistan were captured beautifully. The kite battles were surprisingly riveting thanks to special effects showing the fights from above. The cast was chosen well. I was especially impressed with the child actors. Hassan’s boundless devotion to Amir and love of life was apparent, as was Amir’s self-doubt.

What was missing was the inner-dialogue that was so important to the book. Throughout the book, Amir speaks of his need to feel accepted by his father and how he is willing to do anything to earn his love, including sacrifice Hassan’s friendship. While he feels overwhelming guilt over not trying to prevent Hassan’s assault, he also feels that maybe that the assault and Hassan’s subsequent resignation as servant was 'the price that had to be paid to win Baba.' Without the inner-monologues, we are forced to guess what Amir is thinking based on his actions.

It is during the moments of introspection that we learn throughout the book about how much Amir’s life is affected by his unresolved guilt. When his fiancé reveals to him the secrets of her past, he forgives her, but unlike the book, we are not aware of how deeply he envies her confession, since he still daily feels the burden of unresolved guilt.

Amir’s desperate search for atonement and the fact that redemption was nowhere to be found in the Muslim world he grew up in is what made this such an interesting and important movie for Christians to view. The film offers us a reminder of the freedom that we have because of Christ’s blood and gives us a glimpse of the despair that those that don’t know of his love must experience each day.

“The Kite Runner” is a wonderful movie on it own, and the viewer will find it powerful and thought provoking regardless if he/she had first read the novel. For those that have read the book, be prepared to be somewhat disappointed in what was left out, but still enjoy this high-quality film adaptation.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

The story itself is hard to watch.

Moral rating: Offensive / Moviemaking quality: 2½

Christianity and American policies are not really present in the film of the Moslem world, allowing us to view the action with some neutrality. Of course the US opposed both the Soviets and the Taliban. We are also told that invaders of Afghanistan do not last, which suggest the US will not last long there either. The father Baba is pretty Westernized, and skeptical of the Moslem Mullahs, even as he has a strong sense of honor and morality. Forgiveness, by Baba and Hassan, are a part of their virtue. The Taliban are abusive and hypocritical, as they stone adulterers while taking sexual advantage of orphans. Their Afghanistan is a wasteland. However, their chief spokesperson and villain is concerned with perceived betrayal by exiles like Amir who avoided the hardship of fighting the Soviets. Thus we do see a broken and sinful world where violence leads to more violence, although the chief villain was pretty violent to start with. Amir seems mostly secular too, all though he does pray when he is searching for the missing boy and comes to a mosque.

The kites of the title represent beauty and soaring, if competitive spirit, of the Afghans. (Boys compete in pairs attempting to cut the strings of other kites in scenes that put the Qidditch scenes of the Harry Potter movies to shame.) This is an excellent film with little known middle eastern actors (One played a hijacker in “United 93”) who are great, particularly the children. A positive film worth seeing.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 4