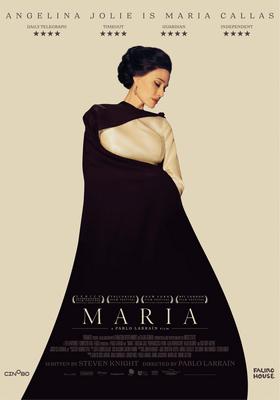

Maria

for some language including a sexual reference.

for some language including a sexual reference.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Biographical Psychological-Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 4 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2024 |

| USA Release: |

November 27, 2024 December 11, 2024 (Netflix streaming) |

World famous, elite opera singer, Maria Callas

The last days of her life in 1970s Paris, as she confronts her identity and life

Maria’s relationships with men

What does the Bible reveal about adultery?

Sexual lust outside of marriage—Why does God strongly warn us about it?

Purity—Should I save sex for marriage?

True Love—What is true love and how do you know when you have found it?

Loneliness

Maria’s negative relationship with her mother

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Angelina Jolie … Maria Callas Lidia Zelikman Kauders (Lídia Zelikman Kauders) … Young Callas - 1930 Aggelina Papadopoulou … Young Callas - 1940 Christiana Aloneftis … Young Callas - 1947 Pierfrancesco Favino … Ferruccio Alba Rohrwacher … Bruna Haluk Bilginer … Aristotle Onassis Kodi Smit-McPhee … Mandrax Valeria Golino … Yakinthi Callas Erophilie Panagiotarea (Erofili Panagiotarea) … Young Yakinthi See all » |

| Director |

|

Pablo Larraín (Pablo Larrain) |

| Producer |

|

The Apartment [Italy] Komplizen Film [Germany] Fabula [México] FilmNation Entertainment |

| Distributor |

“I will sing of steadfast love and justice; to you, O Lord, I will make music.” —Psalm 108

“The devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory… all these I will give you if you fall down and worship me.”

“You are not a peasant girl. You are Maria Callas playing a peasant girl.” —Luchino Visconti directing Maria Callas as Amina in a production of Bellini’s “La Sonnambula”

There will never be another Maria Callas. She possessed what was arguably the best voice of the twentieth century. Hers was not a perfect instrument; it could be sharp, shrill and at times hammy, but no singer has matched the drama and the passion that she brought to each coloratura note she sang.

Callas had a short career; she died in 1977 at the age of 53; but it was an illustrious one. Her performances thrilled audiences around the world while the recordings and film clips that remain from those times still cast a spell.

Chilean director Pablo Larrain’s film, “Maria,” alludes to the diva’s common beginnings; born in the U.S., she emigrated at a young age to Greece where her mother made her sing the Habanera from “Carmen” to occupying Nazi soldiers; and to her rise to fame in roles such as Norma, Anna Bolena and Tosca, but her career high points are for the most part glossed over. There are more scenes of curtains coming down than of curtains rising, which is fitting for a film that covers up more than it reveals.

Callas’ well publicized private life of romance, adultery and betrayal is also given the side show treatment. For someone who lived a good deal of her life in the spotlight, nothing shines bright here as if her life and her career were, as Shakespeare would say, “a mere walking shadow.” Larrain’s Callas too often winds up a bit player who gets second billing to the likes of Marilyn Monroe, John and Jackie Kennedy and the family and friends of a Greek shipping tycoon.

Narcotics play prominently in the plot to the point of making the film seem anesthetized, even paralyzed. The opening introduces us to Maria Callas, not as a life force but as a corpse. Her body is discovered by servants in one of the grand rooms of the singer’s Paris apartment where she has become a recluse in hopes of staging a comeback, or as Norma Desmond in “Sunset Boulevard” would say, “a return.”

Before her death, Callas spends most of her time wandering from bedroom to parlor to kitchen chatting and arguing with the help, playing cards with them, and ordering them to move a grand piano from one space to another. That clumsy and too often-repeated dance move had to be some kind of recurring motif but I gave up trying to figure out what it was.

Callas occasionally leaves her home to wander the Paris streets and the Tuileries gardens while she is interviewed by a documentary film crew, and to slip inside a concert hall to rehearse for a possible future performance. The drug induced haze of the main character, and of the film’s impressionistic aura, make it hard to decipher if the events are real or imagined. Larrain seems to have lost the perception and the reverence he displayed in his earlier biopics, “Jackie” (2016) and “Spencer” (2021). Instead, he callously returns to mocking celebrity as a sordid form of idolatry as he did in his earlier Spanish language film, “Tony Manero” (2008).

There is no gloss in this sleepy biopic, and no soul. The peasant girl, Amina, whom I referred to in one of the introductory quotes, has indeed been stripped of the diamond necklace that Visconti instructed Callas to wear while she performed in “La Sonnambula.” Incongruous as it was for a poor girl to donn such jewelry, it was quite congruous, and in some way real, for a celebrated diva to do so. Any sense of what is true, whether it be part of the visible world or the promised invisible one, is ignored by Larrain. Faith assures us that what is now invisible will one day be, indeed, visible. Art can do that to a lesser extent by opening up something inside us and letting us see what we believed was not there. Visconti understood that; Larrain does not.

Maria Callas was not a great beauty; however, she could convey beauty from the stage and often, if not always, in front of a camera. Angelina Jolie, a capable actress and one of today’s stellar faces, is unable to project the “je ne sais quoi” magical beauty that Callas imparted. More surprisingly, Jolie seems incapable of portraying the reality and the pain of the trade-offs that must be made when one finds oneself in a conflicted relationship while in the public eye.

Haluk Bilginer plays Aristotle Onassis, the man Callas left her husband for, and her one true love. Bilginer seems to enjoy his supporting role, something Onassis would never have accepted in real life. The shipping tycoon refers to himself several times as “ugly,” but such an adjective is not as harsh as it might sound when said with a wry smile and spelled with the letters: M-O-N-E-Y.

Onassis obviously had a certain something besides wealth, and that something comes across well in the performance of the actor who plays him. After all, Onassis won over the hearts of the twentieth century’s two most glamorous women: Jacqueline Kennedy and Maria Callas. Whatever that something was, Larrain’s film could have used a shot of it.

- Vulgar/Crude language: F***ing (5), F**k (2), F**k off (2)

- Sex: Moderate— No sex scenes, but references to sexual relationships. Mother apparently sells her 2 daughters to soldiers, with the result implied but not shown. Girl starts to remove her dress for soldier, but is stopped. Adulterous relationship of Callas and Onassis. Implied adultery between John F. Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. Comments about an abortion or miscarriage.

- Drugs/Alcohol: Moderate— Callas’ addiction to Methaqualone, a hypnotic sedative (aka Mandrax, Sopor and Quaalude). Drinking wine. Smoking.

- Profane language: G*d (3), H*ll (2)

- Violence: Minor

- Wokeism: Minor

- Nudity: None

- Occult: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.