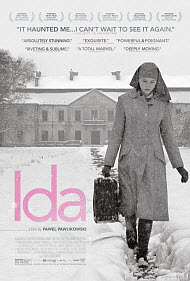

Ida

for thematic elements, some sexuality and smoking.

for thematic elements, some sexuality and smoking.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 20 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2013 |

| USA Release: |

January 23, 2014 (festival) May 2, 2014 (7 theaters) June 6, 2014 (87 theaters) DVD: September 23, 2014 |

confronting the past

anti-semitism / persecution of Jews / Jewish discrimination

Stalinism / Communist society

orphans in the Bible

family secrets

murder of family/parents

religious faith

loss of virginity

PURITY—Should I save sex for marriage? Answer

drunk driving

CONSEQUENCES—What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

SUICIDE—What does the Bible say? Answer

If a Christian commits suicide, will they go to Heaven? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Agata Kulesza … Wanda Agata Trzebuchowska … Anna Dawid Ogrodnik … Lis Jerzy Trela … Szymon Adam Szyszkowski … Feliks Halina Skoczynska … Mother Superior Joanna Kulig … Singer Dorota Kuduk … Kaska Natalia Lagiewczyk … Bronia Afrodyta Weselak … Marysia See all » |

| Director |

| Pawel Pawlikowski — “My Summer of Love” (2004), “Last Resort” (2000) |

| Producer |

|

Canal+ Polska City of Lodz See all » |

| Distributor |

| Music Box Films |

The Polish film, “Ida”, directed by Pawel Pawlikowski from a screenplay by Pawlikowski and Rebecca Lenkiewicz, is about a search for identity and truth in a world that ignored and suppressed both. It is an almost perfect film whose structure, pacing and tone fit the story like the modest but tailored nun’s habit that the main character wears as if it were her own skin. Her short veil, modest skirt, tailored coat and square suitcase comprise the armor that she dons before she faces a world mostly unknown to her, one that has given her very little and promises her less.

Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is an 18 year old postulant who has lived in a Polish convent since she was brought there as an orphan shortly after her birth. She appears to have little, if any, knowledge of life outside the convent walls.

The film opens with Anna restoring a statue of Jesus, an image of divine mercy that has a special significance for the Polish people. Anna and the other postulants carry the statue through the snow and place it in a small grotto in front of the convent, a huge building that seems to house only a few nuns. There are just two other novices besides Anna who are about to take their final vows and become permanent members of the order. These few hold the future of both their fragile country and its uncertain faith in their hands.

The film is shot in black and white, with a tinted haze that makes the images look like vintage photographs. The interior lighting is muted, sometimes muffled. The exteriors give a sense of large distances cut short, of dark forests and crumpled roads that are best left unexplored because they hide too many secrets. The director avoids large panoramic shots. He keeps the scope intimate and soft. “Ida” is a chamber piece, more a sonata than a symphony, a watercolor that may not dazzle as an oil painting would, but whose subject stays with you long after you’ve looked away.

Anna thought she had no living relatives, but her mother superior informs her that she does have one, an aunt. Anna is reluctant to leave the security of the convent in order to meet her. In a strict but benevolent manner, the senior nun tells her that she must confront that part of her life before she takes her vows. It’s a “Climb Every Mountain” scene without the color and the pomp.

Up until now, the filmmaker has given us no sense of historic time or place. That soon changes when Anna reaches her aunt’s apartment, and comes face to face with her one blood relative. We find ourselves in 1960s Poland, a land where Communism has taken root for some time, enough time to blunt a people’s spirit but not enough to tarnish all the luster of what was once a bright and bountiful culture. This is not the 60s of the Western world; the bright colors of Carnaby Street, lava lamps, and Peter Max posters have passed this land by.

Nonetheless, her aunt, Wanda Gruz (Agata Kulesza) lives in a large Belle Époque apartment and drives a car. She dresses fashionably, and has an air of glamor that makes you think she might be an artist, perhaps a musician or an actress. She had to curry some favor to have acquired such privileges in a Communist block country. We soon learn that Wanda is a judge, a former state prosecutor whose job it was to send “enemies of the State” to prison and sometimes to their deaths. In her heyday she had been dubbed “Red Wanda.”

Wanda soon takes over the movie. She is a fully realized character where Anna is a budding one. Kuleza plays Wanda with both ferocity and warmth. It is a great performance, one that too often overshadows Trzebuchowska’s Ida. The latter is touching, and she comes off remarkably well in this, her first film, but she is no match for the veteran Kuleza who burns with grit and pathos in every scene.

Despite her beauty, intelligence and success, or perhaps because of them, Wanda is world weary and cynical. She harbors no illusions about the world or about herself. She chain smokes; she drinks, usually right from the bottle; she drives drunk, not haltingly but as if she were a charging charioteer; and she repeatedly sleeps with men she picks up in bars. She does not do these things in the hope that repeating them might one day bring her what she is missing in life. She performs these self-destructive acts out of habit, one that might have been born of guilt or shame, and she knows all too well where they are leading her.

Wanda informs her niece that she was not born with the name Anna and that she was not born a Christian. Anna’s real name is Ida Lebenstein, and she is Jewish by birth. Her parents—Ida’s mother was Wanda’s sister—were killed by Poles under the direction of the Nazis when Ida was a baby. Wanda and Ida (formerly Anna) drive together to the town where Ida was born in order to find her parents’ remains in the hopes of giving them a proper burial.

The traveling scenes are reminiscent of many a road movie (“It Happened One Night,” “Y Tu Mama Tambien,” “Little Miss Sunshine,” “Wendy and Lucy”), but the landscape in “Ida” is not dramatic or inviting or even all that instructive. The lessons in this film come from within the human heart, not from the land. If anything, the Earth seems fatigued from burying and leveling man’s dark secrets. It has nothing to give back save for a few remains. A gravedigger (who longs to bury his own past) excavates the hidden remains of the Lebenstein family, and hands Wanda her sister’s skull. She wraps it gently in a headscarf. She and Ida put the remains in the trunk of the car, and drive them to a graveyard where there is a family burial plot. They quietly bury those remains in a cemetery that is in the terminal stages of neglect and decay. Most of the headstones have crumbled and fallen over.

The search for Ida’s family may be over but the lives of the searchers have reached a crossroads. I left out a number of details about the quest itself because I don’t want to spoil more of the plot than I already have. This seemingly simple story is rich in small details and discoveries that are played subtly, yet have immense power. In finding each other, Ida and Wanda have found themselves, but those discoveries lead to mixed results for both.

Ida meets a jazz saxophonist, and the two have a romantic encounter, but it is not an awakening for her. Ida’s entrance into the lay world is awkward and more than a bit sad. Whether watching her new beau from behind an arch while he is playing with his band or looking at him over her shoulder in the bedroom, she is not a part of the action. She continues to be an outsider. She is uncomfortable when she takes off the nun’s habit, and whether she puts on heels or a dress or a bedsheet or even a lace curtain, she stumbles and cannot move forward. She desperately seeks a starting point.

Wanda, on the other hand, seems fixated on an end point. Her odyssey is encapsulated brilliantly in one of the movie’s best passages. Actually, it is one of the best passages ever captured on film. It tells a life story, its rise and its fall, in a few short minutes. Bach plays in the background as Wanda has yet another one-night stand and follows the “morning after” ritual that addicts, especially sexual addicts, know all too well: the bath that is never cleansing enough, the hunger that makes one eat to fill a void that cannot be filled, and the siren call of a window ledge. These few stark but jarring images, especially the scene in which Wanda sits clutching herself in the bathtub as the light quickly fades from her eyes, concisely yet compassionately depict the shipwreck that results from a compulsive act that, after the fact, one cannot understand why one took the boat out in the first place.(“Everyone who commits sin is a slave to sin… if the Son makes you free, you will be free indeed” —John 8:36.)

“Ida” is full of human sorrow and tragedy, but it shows how strength grows out of human weakness, and how guilt is often left to the guiltless to expiate. This is the best fiction film about the Holocaust that I have seen. I cherish this small gem much more than I do the epic movies made about the same subject.

The movie begins with the heroine carrying an image of Christ home. The outcome of her story, and ours, depends upon letting Him return the favor.

Violence: Moderate / Profanity: Moderate / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

Then we meet Wanda, her aunt, who is entirely opposite and seems to be taking in as much of the world as she can in a self destructive way with her chain smoking, drinking, and sleeping around. In an effort to get to know Anna, she flat out asks her if she ever has any carnal thoughts. Anna’s negative answer causes Wanda to say, in so many words, that she should know what she is missing before taking her vows.

We find out, at least in my opinion, that Wanda’s self indulgence is merely her way of escaping her past. What is at the end of a road like that? When you have trouble forgiving yourself, then you must realize that Christ has unconditional love and forgiveness for you, and when you accept His grace, then you can learn to forgive yourself no matter what you have done.

As for Anna, she goes on a little trip of self-discovery herself. The most satisfying element of this film is that she finds out that the world has nothing that can satisfy her like Christ can.

I gave it a neutral rating because of a couple of scenes that were a bit disturbing.

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

I was reminded of the Czech new wave films “Loves of a Blonde” and “Closely Watched Trains” in the secular moments and the angst ridden search for faith in Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light during the more spiritual scenes. The cinematography, direction and acting are all superb. This is a lovely, beautiful film that has respect for its intended audience.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5