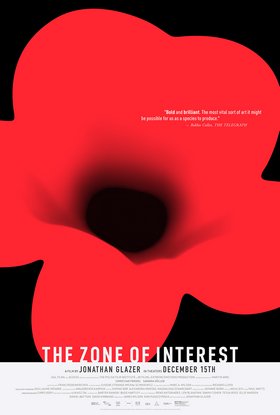

The Zone of Interest

for thematic material, some suggestive material and smoking.

for thematic material, some suggestive material and smoking.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | History War Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 45 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2023 |

| USA Release: |

September 1, 2023 (film festival) December 15, 2023 (limited) February 2, 2024 (wide release) |

Based on true story

Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp in Oswiecim, Malopolskie, Poland

German Nazi genocide of Jews

The Holocaust

Complicity

About the fall of mankind to worldwide depravity

What is SIN AND WICKEDNESS? Is it just “bad people” that are sinners, or are YOU a sinner? Answer

World War 2

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Sandra Hüller … Hedwig Höss Christian Friedel … Rudolf Höss Freya Kreutzkam … Eleanor Pohl Ralph Herforth … Max Beck … Schwarzer Imogen Kogge … Linna Hensel Ralf Zillmann … Hoffmann Daniel Holzberg … Gerhard Maurer See all » |

| Director |

|

Jonathan Glazer |

| Producer |

|

A24 Access Entertainment [England] See all » |

| Distributor |

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself.” —Matthew 22:36-40

“No. Only two and a half million—the rest died from disease and starvation.” —Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp, when answering to the charge that he murdered three and a half million people

“The biggest mistake in my life was that I believed everything faithfully which came from the top, and I didn’t care to have the least bit of doubt about the truth of that which was presented to me… In all your undertakings, don’t just let your mind speak, but listen above all to the voice in your heart.” —From a letter to his son, written by Rudolf Höss, before his execution for war crimes

Jonathan Glazer’s film, “The Zone of Interest,” written by Glazer and Martin Amis (upon whose novel the screenplay is based), opens with a long shot of a family picnic. The setting is bucolic and soothing, almost dreamy. The sky is an azure blue, the hills, a lush green. Even the churning river looks placid. Endearing blond children frolic in the grass and splash each other while playing along the water’s edge. They are living a life of promise in a promised land.

I found myself longing for a close-up of the idyllic setting, to be closer to such carefree leisure, to such happiness. But Glazer has his viewer step back, asking us to keep not so much a safe distance as an analytical one. He shuns the zoom lens, refusing to give us the luxury of focusing on, and taking to heart in, any single event, gesture, or expression. It’s not that he wants to gift us with the big picture. He wants to stop us from escaping it.

After the picnic, the family returns to their nearby home, a stately villa with exquisitely manicured gardens and a swimming pool. The grounds are surrounded by a stone wall, a high enclosure over which ivy and flowers grow on trestles. The property is mostly quiet except for chirping crickets, singing birds and the voices of high-spirited children.

Occasionally, on the other side of the stone, a pop may be heard, something akin to a muffled gunshot. Other times, a scream intrudes on the silence. Such interruptions register no response from the people living inside the walls. They pay virtually no attention to what they hear, or what they may catch a glimpse of, on the other side of the wall. In the distance one can see a smokestack, a black tower that puts out a constant stream of fire and smoke.

Inside the home is a perfectly set table laden with fine china and fine food. Sometimes Hedwig, the lady of the house, spreads silk dresses on the table, offering them as gifts to her neighbors or to the house staff she employs. On one occasion, there is a fur coat. Little is said about the origin of the clothes, but it is obvious that the women sorting through them know exactly where they come from.

The filmmakers take care, and time, to reveal how difficult it is to keep such a fine house. To adorn and to maintain the Shangri-La style abode revolves around following daily routines and paying close attention to detail. Everyone involved in its upkeep must follow strict orders while not taking the time to question how or why. They just do it, and rarely do we see a chink in the sparkling armor.

Now and then, there are some unsettling hints of a lurking menace: a colicky baby who cries incessantly, an obstreperous dog who resists all commands, some dry heaving on a staircase, and the occasional soft utterance that unmasks a need to keep under wraps a reserve of cold barbarity.

Rudolf, the man of the house, is calm but deliberate. He is a kind and concerned husband and father. He denies his wife and children nothing, devoting whatever free time he has to his five children, even reading them bedtime stories after what must be long and grueling workdays.

When not at home with his family, Herr Höss, or Commandant Höss, oversees the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland. The film, based on the real-life story of the Höss family, does not take us inside the camp. Most of the action takes place within the walls of the villa.

The dramatic arch of the story traces the anxiety that results from the Waffen SS decision to transfer Rudolf Höss from Auschwitz to another assignment. His wife is furious over the decision, and especially over having to move. She has, after all, helped build a sumptuous home in an ideal location for herself and her family. Giving it up, even if it means career advancement for her husband, is not an option for her. He can go, she tells him, but “I’m staying here, thank you.”

Rudolf has, indeed, helped build his concentration camp into one of the most well-organized and efficient camps in the Third Reich. While his wife follows a strict regimen at home to keep her house in respectable order, Rudolf follows his own proscribed set of orders to ensure that his operation runs like a well-oiled machine.

We come to learn just how much Höss has accomplished when he meets with other members of the SS to discuss stratagem on how to deal with the large influx of train travelers heading East. They look to Rudolf for advice about how to “deal with” the expected increase in volume. There would be over 400,000 passengers from Hungary alone.

Höss was tasked with not just the selection and management of those passengers, but with the design of the camp gas chambers as well. He discusses with architects the intricacies of the chambers, how the killing and the burning are the easy parts; how it is the clean-up that poses the most difficulty, and takes the most time. He proposes solutions. His consultants are impressed.

Glazer’s film is unlike almost all other Holocaust films. By not directly showing the Final Solution atrocities, he does not allow us to pass judgment easily. By having us step back and take a long view of the personalities of the people who perpetrated the horror, he has us identify with them before we evaluate them.

And identify I do. When I reflect on my life, i.e. when I pray, I realize that most of my existence is taken up by everyday maintenance which I get done by steadfastly adhering to a routine. It is not easy to stop and look at the big picture, to ask myself what in that picture is good and what is bad. Too often, I find myself “worried and upset about many things…” and my conscience, and my spirit remain needful. I certainly have not “chosen the better part” (Luke 10:41).

“The Zone of Interest” does not allow me the luxury of saying “I could never take part in such an abomination.” By going about a quotidian routine, by accepting and obeying orders of questionable moral merit on a regular basis, and by being too attracted to the finer things that this world has to offer, I do not ask myself enough: “Of what else am I capable?,” especially in these days when phrases such as “from the river to the sea” and “by any means necessary” are being shouted all around me. Have I once stood up to those shouts?

“The Zone of Interest” is a small masterpiece, a quiet drama, but a scorching one. It is expertly crafted, tuned to precision, and highlighted by exceptional performances. Sandra Huller’s Hedwig Hoff is regal and dignified, but she never allows her character’s innate imperiousness to dampen her surface bonhomie. Huller gave this year’s best film performance as the tortured widow in Justine Triet’s “Anatomy of a Fall,” but I admired her just as much here.

Christian Friedel as Rudolf Höss matches her in a role that is not easy to bring off. The camera shows him from a distance and often in profile. It’s hard to read his features and to get a sense of his eyes. He and Glazer refuse to hand us that mirror into the soul. They make us look for it. But Friedel gets it right: he fleshes out the trapped man who is most comfortable in his cage, and is unable or unwilling to find a way out.

In German, with English subtitles, Glazer’s film is a true original. It is a delectable bon-bon whose center exposes the darkness of the human heart. It is the most picturesque of all Holocaust films. And, therefore, the most chilling.

- Violence: Moderate

- Sex: Moderate

- Profane language: Mild

- Drugs/Alcohol: Mild

- Vulgar/Crude language: Minor

- Nudity: Minor

- Occult: None

- Wokeism: None

Q & A

About the fall of mankind to worldwide depravity

What is SIN AND WICKEDNESS? Is it just “bad people” that are sinners, or are YOU a sinner? Answer

Are you good enough to get to Heaven? Answer

How good is good enough? Answer

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.