X-Men: The Last Stand

for intense sequences of action violence, some sexual content and language.

for intense sequences of action violence, some sexual content and language.

Reviewed by: Michael Karounos

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Teens Young-Adults Adults |

| Genre: | Sci-Fi Superhero Action Fantasy Sequel |

| Length: | 1 hr. 45 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2006 |

| USA Release: |

May 26, 2006 (wide) |

X-Men Origins: Wolverine (2009)

What’s wrong with being gay? Answer

Homosexual behavior versus the Bible: Are people born gay? Does homosexuality harm anyone? Is it anyone’s business? Are homosexual and heterosexual relationships equally valid?

What about gays needs to change? Answer

It may not be what you think.

Can a gay or lesbian person go to heaven? Answer

If a homosexual accepts Jesus into his heart, but does not want to change his lifestyle, can he/she still go to Heaven?

What should be the attitude of the church toward homosexuals and homosexuality? Answer

Read stories about those who have struggled with homosexuality

Christian ministry to ex-gays: exodus.to

Family Research Council article on the supposed gay gene

Catholic article on the gay science supposedly supporting the gay gene theory

| Featuring |

|---|

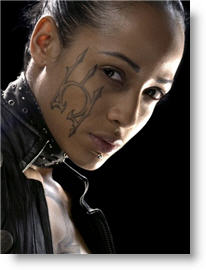

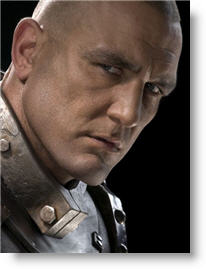

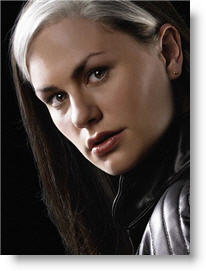

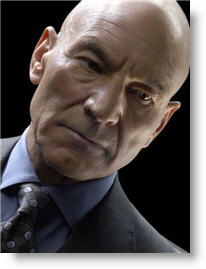

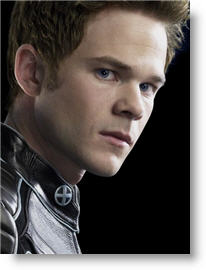

| Hugh Jackman, Patrick Stewart, Famke Janssen, James Marsden, Ian McKellen, Anna Paquin, Rebecca Romijn, Kelsey Grammer, Ben Foster, Ellen Page, aka Elliot Page, Bill Duke, Olivia Williams, Daniel Cudmore, Shawn Ashmore, Vinnie Jones, Aaron Stanford, Cameron Bright, Michael Murphy, Kate Nauta, Shohreh Aghdashloo, Mei Melancon |

| Director |

|

Brett Ratner |

| Producer |

| Avi Arad, Lauren Shuler Donner, Ralph Winter |

| Distributor |

“Take a Stand”

The plot of “X-Men: The Last Stand” repeats the conflict of the first two movies in which the mutants are divided into pro-human and anti-human camps. The catalyst for the conflict is the creation of a new drug which alters the mutant gene and transforms the mutant into a “normal” person. The sub-plots focus on Cyclop’s inconsolable loss of Jean, Rogue’s inability to cope with the distance her power places between her and Bobby, and Wolverine’s unrequited love for Jean. Additionally, there is an interesting twist between Magneto and Mystique that reinforces this theme of relationships, what bonds them, and what breaks them.

Professor Xavier’s team acquires new characters like the Beast (Kelsey Grammer) and Angel (Ben Foster), while Magneto picks up a prickly mutant (Luke Pohl), and my favorite, Multiple Man (Eric Dane), who has the power to replicate himself. Dane’s engaging smile and well-delivered lines enables him to do more with less material than almost any actor in the film. However, Ellen Page, aka Elliot Page, as Kitty Pryde, the girl who can pass through matter, steals nearly every one of her scenes. She manages to project a strength that is simultaneously intelligent, vulnerable, and yet innocent, an impressive feat for a young actor. She’s one to watch for in the future.

The story follows Magneto and his bunch as they gather mutants and attack the Island of Alcatraz, the former prison which has been turned into a facility to manufacture the anti-mutant serum from Leech’s blood. Leech (Cameron Bright), whose power is to negate the power of other mutants, is kept in a clinically pristine room where he sits on the linoleum floor and plays video games. Bright infuses his acting with the same tortured quality that Haley Joel Osment brought to the “The Sixth Sense” and also turns in a strong performance in comparatively little screen time.

The movie makes much of Jean, now Phoenix, as being the final stage in the evolution of mankind. Magneto calls her “A goddess!” and she may very well be the sacred feminine that “The Da Vinci Code” misplaced. Arguably, however, it is Leech who is the last mutant because his mutation negates all other mutations. His pre-eminent quality is one of kindness and it raises the profound question that the matter of difference, of mutation, which each of the movies constructs as a metaphor for racial and sexual identity, is internal and not external. To quote Martin Luther King, the movie seems to suggest that one’s identity does not depend on the (blue) color of one’s skin, but on the content of one’s character. Hence, the issue of whether to remain a mutant or to become fully human, and to whom one owes one’s allegiance once such a change takes place, has more to do with inner values like justice and love, than with external distinctions like color and the desire for power.

One of the greatest flaws in the movie is how it dispatches with a major character. If one assumes that this is the last movie in the franchise, than the death of the character is strangely dismissive. I have no special knowledge, but the character’s death is so counter to film convention which demands that such moments are played for maximum emotion (as another is played later in the film), that I believe the character will be found alive in a sequel. Unlikely, but it’s the only rationale that would explain such a strange disappearance.

Another fault is the prolonged sequence with the Golden Gate Bridge, a silly and extended piece of CGI trickery which probably cost a fortune to make and contributes absolutely nothing to the excitement, to the story, or to any character. The movie was 30 minutes shorter than the other two probably because special effects ate up so much of the budget. Ratner and the writers should have spent that time and money constructing backstory for the new mutants who basically have cameo roles (Angel) or wooden parts (The Beast).

The Beast, unlike Aslan, is a tame Beast and is not quite convincing as either a scientist or a scary creature. He’s pretty much blue and strong and punches hard. The writers miss the point in their portrayal of the Beast even though they try to copy the comic book version. He is called the Beast because of the contrast between his intellectual and subliminal natures. As Xavier remarks of Jean, “I’m trying to restore the psychic blocks and cage the beast within.” This is the universal commonality between mutants and humans, between people of different cultural backgrounds. We can either let our reason form the basis of our relationships, or let our ids fight it out. Xavier’s group represents the first solution; Magneto, in his Nitzschean drive for power, prefers the latter, the “oberman” solution.

Likewise, the conclusion of the fight between Iceman and Pyro is anti-climactic, as is that between Wolverine and a mutant who can regenerate limbs. In those instances, the movie settles for juvenile humor in moments where an imaginative darkness would be more appropriate to the material. One example of a convincing scene is the fight Wolverine has with a mutant who throws darts. It’s not as good or as long as his fight in the second movie, but it has the proper serious tone. Chopping people’s limbs off is not funny, and in this scene the intent of the two mutants to kill one another shows a serious and adult understanding. Violence should never be portrayed casually, flippantly, insensitively, or gratuitously. Violence is sometimes necessary; it is never funny.

As alluded to above, the film’s principle weakness is that the writers injected more exposition than backstory. There are several overt references to race and a number of covert references to homosexuality. At one point the Professor portentously says to the “colored” Storm: “Things are better out there. But you of all people know how fast they can change.” Later, the “colored” Mystique refuses to respond to a question because, she indignantly claims, “I don’t answer to my slave name.” On another occasion, a black prison guard shouts at Mystique as she assumes the form of the President of the United States. The camera goes to close-up and the black guard says: “Mr President: shut up!” Mystique next changes to the image of a small white girl and the guard shouts: “Shut up, *****!” The acute pretentiousness of the dialogue and camera angles make it clear that this was the film’s symbolic “speaking truth to power” moment, full of sound and banality. On the one hand, Mystique affirms the privilege of victimization with her color; on the other hand, the black officer negates it with his abhorrent conduct, which he later pays for. These are contradictory and ambiguous messages about race in the movie and both satisfy and unsettle audience members of the left and the right. I think that’s as it should be.

There are also specifically gay moments in the film. During one of the protests a television reporter says, “Some are desperate for this cure while others are offended by the very idea of it.” This is the case in our culture today where ex-gays who are born-again Christians travel the country speaking about their faith and newfound straight life. This offends gays because many believe there is a gay gene. (Coincidentally, there is a report on the “gay gene” in the current issue of The Advocate, the national Gay and Lesbian magazine.)

For viewers who find the assertion that there is a gay subtext difficult to believe, Carina Chocano in the L.A. Times writes:

“the mutant concept in “X-Men” is particularly applicable to the gay experience, a metaphor that was cleverly pinged and poked in the films directed by Bryan Singer” [i.e., the first two X-Men movies].

Roger Ebert observes,

“There are so many parallels here with current political and social issues. I thought of abortion, gun control, stem cell research, the ‘gay gene’ and the Minutemen.”

Phil Villarreal comments:

“The first [movie] could be read as a parable advocating for gay rights. The second was laced with commentary on race relations and the AIDS epidemic.”

Walter Chaw had the strongest reaction, exclaiming, that the movie is…

“an example of what can happen when a homophobic, misogynistic, misanthropic moron wildly overcompensates in a franchise that had as its primary claim to eternity that it was sensitive to the plight of homosexuals,” and he calls the movie Brett Ratner’s “painfully queer X-Men.”

And he has a point, for the movie is “painfully queer” in the sense that it both sympathizes with and seems to criticize the gay movement. A gay writer, Michael Musto, satirically pronounces it “a giant metaphor for the ex-gay movement!”

Note: A World Entertainment News Network article titled “McKellen wants gay sex scene” reported:

“Actor Sir Ian McKellen complained on the set of upcoming sequel “X-Men: The Last Stand”, because he wanted his character Magneto to have some gay sex scenes. “The Lord of the Rings” star, who has been openly gay since 1988, insists a homoerotic sub-plot would have enhanced the movie. McKellen tells Empire magazine, ‘He hasn’t been given a love line, which I think is a pity. It would be wonderful if the camera hovered over Magneto’s bed, to discover him making love to Professor X.’ However, McKellen admits he needed camera trickery to help him match Magneto’s muscular physique.

He adds, ‘I’d like to see him at the gym, because in the comics he has the most amazing body. I’m the slimline version of Magneto, but of course, these days you could morph my body into something really fantastic.’”

If, as gay and liberal writers seem to agree, the movies signify the gay experience, than they clearly suggest that there are “good” gays and “bad” gays: the good ones assimilate while the bad ones stage violent protests. The same is true of race and of the abortion issue. In other words, I’m suggesting that either the writers, or Ratner through his direction, opted for a more complex portrayal of minorities in which they are not only victims but victimizers. This is not a politically correct message and is why, I believe, the mainstream critics so strongly dislike the movie and Ratner’s direction. It goes against multi-cultural orthodoxy which dictates that minorities must always be saintly (or angry) victims and white men and the institutions they represent must always be stupid or evil. In this movie, the preponderance of the bad mutants, if anything, comprises more minorities, a conspicuous reversal of the race message in the “Matrix” movies and a fact that troubles the most liberal reviewers.

Similarly, the issue of abortion and choice is handled with a double-edged ambivalence. In at least two scenes, viewers observe crowds of protestors outside the serum clinic where mutants line up of their own free will to receive the injection to effectively kill the mutant life within them. “We don’t need a cure!” the protesters shout, and, indeed, no one is forcing them to get one. But the spectacle of the crowd is a highly complex one because it elicits the common image of protests outside abortion clinics, thus criticizing both those who protest abortions and those who get them. In keeping with my interpretation, I believe this represents an indictment not of any particular position, because right can be found on both sides of any given issue, but it indicts the means by which grievances are expressed. The movie, ironically, is against violent expression and demonstrates that violence, regrettably, must sometimes be used to counter those who resort to violence first. Hence Magneto’s self-justification that “they have drawn first blood.”

Intellectually, the movie promotes dialogue, negotiation, and assimilation. Emotionally, it shows the love that Rogue has for Bobby, that Cyclops and Wolverine have for Jean, and, in a poignant moment, the love that the Professor has for Wolverine. (Whether that is a gay moment I will leave to the gay reviewers to determine.) On the other hand, it shows the lack of love that Magneto has for Mystique. Teamwork and sacrifice are emphasized both at the beginning and the end of the film, while the ego-centeredness of Magneto, Phoenix, and even Juggernaut (Vinnie Jones) are punished.

Admittedly, the first half of the movie is a choppy mess in which the pacing seems mechanical and episodic. And while every reviewer blames director Brett Ratner for this and other crimes against humanity, much of the responsibility lies with the story-telling. Unlike the first two movies, neither Brian Singer nor David Hayter were involved in the writing which I believe explains the poorer dialogue, the thinner characterization, and the heavy-handed cultural references.

The movie is violent, and it has more nudity than any conservative Christian can be comfortable with, showing extended shots of Mystique’s naked chest and back. Depending on a family’s acculturation, those scenes, brief though they are, may be deal breakers. (For those who would like to take a chance on the content, the more egregious scene with Mystique occurs when she begins to walk out of the truck.)

It’s a shame, because, aside from those scenes and three swear words (two “b” and a “d” word), “X-Men: The Last Stand” is more gratifying for fans than not, and more complex than either of the first two films in seeming to portray both sides as being sometimes rational, sometimes irrational—sometimes right, sometimes wrong. Ultimately, the Professor demonstrates true love and grace for Jean, as a Father might His child.

I cautiously recommend the movie for Christian audiences, but with a heavy emphasis on the caveats in the previous two paragraphs.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Moderate / Sex/Nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

As for Professor X, he has a paternal love with all his X-Men and other students. Whatever meaning viewers take beyond this (i.e. between Prof. X and Wolverine) is pure fabrication.

I am surprised no one seemed to notice the scene between Warren/Angel and his father near the end of the movie. I do not want to spoil anything. But in these days where rebelling against “bad” parents is encouraged, it was very encouraging to see Warren’s love for his father manifesting itself.

In terms of continuity with the comics, I was thrilled to see Kitty/Shadowcat brought in as one of the team members (although the movie should have shown why she was elevated to this position). Ellen Page, aka Elliot Page, I agree, did an excellent job portraying her character. Disappointingly, Nightcrawler (you remember him from X-Men 2?) was no where to be found. This made no sense whatsoever. My greatest disappointment, as with the first two movies, was Halle Berry’s portrayal of Ororo/Storm. Storm in the comics is a motherly figure; she gained this in her home in Africa where she used her gift (mutant ability) to help her people. We do not see this from storm in the movies.

Finally, there’s Jean Grey’s transformation into Phoenix. In the comics, Phoenix is a cosmic entity that takes Jean’s form after enveloping Jean in a healing cocoon from severe radiation poisoning. In taking Jean’s place, Phoenix forgot its true identity and thought it was Jean, and so no one knew the truth. Unfortunately, emotions were foreign to Phoenix. When a mind-bending mutant corrupted Jean/Phoenix, the dark passions were first experienced and enjoyed, and in so doing Phoenix became Dark Phoenix—a creature so consumed with dark passion that it consumed a sun and wiped out an entire solar system, one containing a planet with sensient beings, for the sheer pleasure of the sensations. With the help of other aliens, Professor X was able to put mental blocks on the Dark Phoenix, but only loosely. The other aliens wanted to destroy Jean/Phoenix to prevent her from destroying other suns. The X-Men fought to save her. But Jean/Phoenix, realizing she couldn’t control the Dark Phoenix, and feeling horrified at what she had done, fired a powerful ray gun on herself, ending her life (although the Phoenix force survived—but that’s another long story). The point to all this, considering the time constraints of the movie, I can forgive the changes they made to having Phoenix being Jean’s own ability. It does, however, lessen the true essence and power of the Phoenix.

By the way, if you have not seen the movie yet, make sure you stick around until after the credits. One more critical scene is given then.

Average / 3

- For content: there was more sexuality. That consists of a groping/make-out scene with some suggestions, but no nudity or anything perversely graphic in it. Then there is a view of a woman nude, but nothing directly shown with it being a side view (I can’t get into any more detail or I’ll spoil something for you).

- For language: there is a little more than the last two. I didn’t catch the token F-bomb, which surprised me actually, but there are some blatant remarks—one being to a little girl, but it isn’t “exactly” to a little girl (again, I can’t get into it).

- For violence: there was a lot more, but nothing that was really gross. Just a lot of kicking, stabbing, shooting, and explosions. The Phoenix looks pretty nasty at times and does some disintegrating moves on some characters. It didn’t seem to be too much for a PG-13 film though.

- As for the quality of filmmaking, it was really impressive, but the writing around the second half was just full of lame one-liners. It’s entertaining and provides some awesome computer graphics, but character development was lacking. Since I’m not a hard-core X-Men fan and have never read the comics, I hear that they at times stray from the original storyline, but did a fairly good job at sticking with the comic book stories.

Average / 5

Average / 5

Average / 5

As far as content, Mystique is still mystique; obviously she wears more in the comics, and I don’t really understand why they didn’t give her a real costume. there is heavy making out and groping in one scene and a few usages of profanities. it is unfortunate that they feel the need to include these things, but it was still far cleaner than most PG-13 movies.

as far the gay agenda behind the film, I don’t know the film makers agenda. I know that some of the dialogue in the past has purposely drawn parallels between the mutant story line and the gay issue (for example, when Bobby’s mom says “have you tried NOT being a mutant” in X2), but I do think the intentional parallels are pretty minimal. No matter the agenda or not, there’s gonna be certain similarities in the two matters. This review is definitely reading too much into it though. …

Average / 4

Average / 3

Excellent! / 4

Average / 3

-There is a full shot of a naked woman barely covering herself.

-There is a very passionate scene between Logan and Jean which isn’t really bad, but could have been taken out or just made a little more appropriate.

-There were a few bad words.

That is really all, other than the violence which really wasn’t too bad. …

Average / 3

Average / 4

Morally, there were a few curse words and the movie is INDEED PG-13 however, I am pleased to see these comic book heroes in real life situations be real and not cartoony and fake. In fact, series like X-Men, Superman, Spider Man, Hulk, Dare Devil and Batman (in particular) were dark stories to be told.

Better than Average / 4

Average / 5

Better than Average / 4

Better than Average / 4

1. Not enough time for certain characters, such as Mystique and especially Cyclops.

2. I could see some people offended by the sexuality in the film, and possible allusions to homosexuality. Homosexuals need to know that most true Christians are not the horrible, bigoted boogeymen shown in movies.

3. The Iceman vs. Pyro fight was a MAJOR disappointment. What could have and should have been a really intense duel between the two ended up being basically just them kind of “arm wrestling” with their powers.

4. No Gambit! He’s one of the coolest X-Men ever, and they didn’t even use him once in the entire series!

Now, for the good parts:

1. The Danger Room scene in the beginning was neat, and exciting.

2. It had some pretty funny moments, such as one sequence when Wolverine has to fight a mutant that can regenerate lost limbs.

3. Although they could have done more with Angel, what they had with him was very visually impressive.

4. Beast! Kelsey Grammer was the perfect choice to play him. I liked how they even had him utter one of Beast’s most famous catch-phrases from the comics.

5. I liked that they used Colossus more in this one than the previous film, though I’d have to agree with the reviewer who was hoping to see a Colossus vs. Juggernaut fight scene. Something like that, if played out well, could have been awesome.

6. The two surprise twists in the very end of the film(You’ll have to wait until after the end of the credits to see the second one), were cool and completely unexpected.

In summary, I think if you liked the previous two films, you’ll like “The Last Stand.”

Average / 4

Offensive / 5

Offensive / 4

On the other hand we have the bad …The profanity wasn’t too bad, but definitely something you need to watch out for. The worst was the sexual content. I felt very uncomfortable in a few scenes. My friend and I just ended up closing our eyes and not watching a couple parts. To me, the sexual content was a huge turn-off from what could have been an otherwise good movie.

Average / 4

Average / 3

I appreciated how one character’s father wanted to change him whether he wanted to change or not, but how forgiving the son was. This showed me that it’s okay to love my parents even though I may not agree with their beliefs or actions.—Perfect example of “loving one’s parents, period.”

There was also an example of how numbers don’t matter in the battle, but which side you’re on (in the OT the battle of 300 v. 10,000). There were six X-Men (persons) in the final battle against ALL the “bad” (or misled) mutants. I felt the nudity in the film was somewhat modest and was not displayed in an erotic light since she did try to cover herself (except for Mystic in blue). However, the sex scene was a bit graphic (although the characters were clothed) and not necessary for the story.

The movie demonstrated how not “caging the beast within” can hurt everyone around you, whether you intend it to or not. I think that thinking one can control the “beast” within while displaying other parts of it in certain situations is an illusion. The make up for Juggernaut was very believable—the actor is actually fairly slender, so much so that even steroids couldn’t have bulked him up that much that fast. Also, anyone who stayed after the credits saw potential future for one character and another character’s loss of powers—or mutation isn’t just a one time thing. Also, I’m glad McKellen didn’t get his wish.

Average / 4

The scene that is the biggest issue for me is the one between Wolverine and Jane. This is very passionate and completely on screen, until he figures out that there is something in her eyes that he doesn’t recognize, and he stops. To me, this is more than I want to see and certainly not my teens. This is quite a long scene and is very seductive.

How hard is it is to not see a movie that is such a great hit and a wonderful fictional art? It’s a great escape for most of us. But do be forewarned; it is a very sexual scene. So you have to decide what is right for your family.

Offensive / 4

This is a movie that is basically all action with a paper thin plot and script. It starts off well, but then deteriorates into nothing more than mindless action-packed fighting and big effects. It does not have the magic that Brian Singer brought in the first two movies. There is very little in character development, with most scenes resorting to battles, military action and mutant powers. The storyline was flat and dull, and most characters (with the exception of Wolverine, and, for her part, the changeling woman) were virtually wooden. Some of the characters, such as Juggernaut and Angel, had wasted characters that this movie could have done without. Most directors make the fatal mistake of thinking that the script and plot do not matter, instead action and SFX does. And this movie is a prime example of that. It seemed to be more of a “last person standing” movie, with well known characters (such as Cyclops and Xavier) falling down like a pack of cards. …One thing that I was also disappointed in is the absence of Nightcrawler from X2. He showed then that even mutants can believe in the one true God and follow him.

In terms of profanity and sexuality, both are fairly mild. There were expletive references such as b****, including one reference made by Juggernaut to a young girl. Both Wolverine and Juggernaut make a few profane expletives throughout the movie. In terms of sexuality, there are really only two scenes to be worried about, one being when the changeling woman gets shot by the formula and reverts back to humanhood, and she lies there with no clothes on. (Thankfully, we are spared from anything concerning there). The other was when Jean tried to seduce Wolverine. However, Wolverine pulled back when he saw the odd look in her eyes.

However, there is one scene that is very interesting. Rogue hears of the cure, and is very excited about it because it means that she can finally become human, rid herself of her bothersome mutant ability and do what normal humans can do. She attempts to run away and meets Wolverine before she goes, who lets her go. She says to him “Aren’t you going to tell me not to go?” Wolverine replies, “I’m not your father, I’m your friend.” Virtually in everyday life, we make decisions, and those decisions affect the consequences of our actions. Some people just want to go with the flow and be like everyone else. God our father would not allow that, even if it makes us different from everyone else. God tells us that as Christians we should make a stand for what we believe in and not “go with the flow” of the world.

Average / 3

As far as I am concerned, there were no good points in the movie. The story was the biggest disappointment because it didn’t seem to go anywhere. At one moment, you’ll see Magneto rallying up some troops. Then, the next moment, you’ll see the X-Men trying to cope with the current stage of their situation. … The main plot was a terrible choice. A “civil war” over a mutant cure-all. It didn’t have nearly as much strength as the plot of the second film. The character mechanics and chemistry were all wrong for this film. From Cyclops to Wolverine, Storm, Jean, even Professor X; the feel of these characters seemed to not work out well.

I could have waited a year or two for a good X3. This one seemed like a rush job to beat “Superman Returns” to theaters. What would have been good for this movie perhaps:

- Sentinels. Not just the one in the danger room, but actual sentinels created by Trask.

- A good plot could have been that the president took Professor X’s message in X2 the wrong way and began to consider a mutant registration act. This would provide more of a premise for Magneto to stand against the government. Also, it could show a struggle as the X-Men try to prove that mutants should be treated as equals. (Jean is not present this whole time).

- …Regarding Christian issues, my only problems are the make out scene between Wolverine and Jean (Phoenix) and the constant nudity of Mystique. Although she’s wearing a body suit, I don’t understand why there’s a need to give off this impression. It’s pointless. I also didn’t like Juggernaut cursing out Shadowcat. She’s a kid for goodness sakes.

All in all, save your money. Consider the X-Men movie story to end at X2. This movie was a real let down.

Offensive / 1

Average / 1

SPOILERS AHEAD—you were warned!! They tried to cram too much in this movie, deaths that are not explained, too much screen time for “the Phoenix” (who is Dr. Jean Gray’s charter), and other characters that we were expecting to be bigger—weren’t! Dr. Gray character is some how wrapped in a “cocoon” in the river—HOW? If she is this “all powerful being” then why did she wait 5 years to emerge? This was a goofy addition to the movie—come on!

The Angel had very small screen time and so did the Multiple Man. I was looking for Night-Crawler from X-2 and never saw him. I think they missed the boat on that one!! He was such a great character! The “Beast” is an awesome addition character! He added so much to the film that think without the Beast—it would have been a TOTAL mess. I was so sad about the deaths in the movie. Something else they could have added towards to end could have been a “fight scene” between Storm and The Phoenix. This would have been more acceptable toward the end. She just stood there at the end fight scene between good and evil mutants. She looked like a robot—and then, she looked like a witch out of a horror movie when she “lost control.” To have Wolverine kill her was just nuts! Why didn’t they just shoot her with the “cure” and let her live?

There was too much killing of main characters. I also didn’t like how main charters from X-1 and X-2 were just dismissed early on in the movie. A perfect example would have been Mystique. She is basically just left in the truck—no help is offered to her by the man she stood by! Magneto! Scott (Cyclops) is also just dismissed. You will see what I mean! Also, Rouge gets cured! WOW! I mean it was so weird. I left feeling very disappointed about this movie. …

Offensive / 5

Offensive / 4

Offensive / 4

Average / 4

Concerning the movie, yes it had some cool parts, but it was mostly just an incoherent mess. The script was awful, it couldn’t find a balance between comic book dialogue and realistic dialogue. Colossus and arch-angel were barely even in it. Cyclops died; for crying out loud he’s the stinkin leader of the X-men and he dies in the first 15 minutes. Juggernaut gets defeated by running into a wall (lame). The fight between Bobby (ice-man) and Pyro, wasn’t even a fight. They build it all up and you want to see these two ex-friends duke it out, but instead, you get a stupid fight that seems to be lifted out of some dumb anime TV show that I watched when I was five. The special effects were sub-par; the stupid bridge scene took up way too much time. The only awesome scene in the film, and one I think justifies seeing the movie, is were Xavier dies, its emotional and the effects look really good…

Finally, I must mention that The Beast just looked fake; isn’t he supposed to be nimble and spry, instead he’s as stiff as a plank of wood. I’m a fan of the comics and the first two movies. A huge fan. This just didn’t live up to the standards. It should of had better character development, and at least have been longer then the first two movies. Its an okay movie, probably not as bad as I make it sound. For someone that likes action movies, and has never read the comics, they will probably love it. But as for now, “Batman” is the reigning comic book movie.

Average / 2

Average / 4

Other things a person needs to consider before watching this film are the nudity and sexuality. Mystique is naked. That’s it, and there’s no rationalizing. She’s less clothed than Janet Jackson was during her wardrobe malfunction, and yet many christians still love these movies. Wolverine and Jean/Phoenix make out in a way that some might call “passionate.” It’s not passion. It’s lust. And the whole scene was gross.

The last thing I’ll mention is the cheap script. The characters were flat and while it’s sad when anybody dies, I just couldn’t care when a certain main character died. The humor was childish and Wolverine especially had some cheesy one-liners that made me grimace. Wait… was it supposed to be funny?

Offensive / 3

Better than Average / 3

At one point in his review, Karounos says of Professor X’s encounter with the “‘colored’ Storm: ‘Things are better out there. But you of all people know how fast they can change.’” While this dialogue here may be construed as a commentary on racial issues (the Professor hinting to the shifting slopes of civil rights in past years), this is, most certainly, a misquote. Professor Xavier remarks that Storm knows “how fast the weather can change.” As Storm’s ability in the movie is to rapidly manipulate the weather, this is less racial commentary than a clever play on words.

Many of the “covert references to homosexuality” that Karounos references are, at best, great stretches of a viewers imagination; and, I fear in a “Da Vinci Code” world of conspiracy, that they will be taken too seriously by potential moviegoers. For you Christians on the border here, this movie is NOT A COMMENTARY on current issues. It’s an X-Men movie, folks. And that’s about how serious the movie gets.

Better than Average / 4

Average / 5

Average / 4

I have to disagree though with the issue of race that this article points out as bad in the movie. When the Professor says “You of all know how fast the weather can change” has nothing to do with race at all. He was talking about how her power allows her to change the weather very easily, and he also was alluding to the fact that the world can change just as easy. When Mystique says she won’t respond to her slave name, she meant her human name and not the name she goes by. None of this was racial at all. What is racial is the discrimination between humans and mutants in the film. We should be accepting to people of all races.

I do have to say though that if you’re under 13 you should not see this movie. It does have a scene of groping and another scene of a naked woman who has covered herself in the appropriate areas with her hands but it is still visually stimulating. Not to mention the few curse words that are scattered through the film.

Average / 4

Average / 4

Average / 5

Average / 4½

Offensive / 5

Offensive / 4

Offensive / 3½

So, that is to say I’m thrilled with the quality of this film, but from a Christian point of view, “X-Men: the Last Stand” is a bit morally ambiguous. However, it does emphasize making the right choices, even when it seems easier for us to make the wrong ones, often it is better for the other person if we do what is right. It also, in regards to the issues of tolerance addressed in the last film, questions whether we most also embrace the beliefs of the person we are tolerating or simply accept them but not necessarily join them. In the end, however, most of the main characters do make the right choices, even if they are hard to make.

Having said that, I can heartily recommend this film to most fans of the first two, although nonstop and sometimes graphic violence, as well as a scene of sexuality and brief nudity, prevent me from giving it an “average” rating and I would only recommend it for children younger older than 15.

My Ratings: Offensive / 4