The Grand Illusion

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Better than Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | War Drama |

| Length: | 1 hr. 57 min. |

| Year of Release: | 1937 |

| USA Release: |

June 4, 1937 (France) September 12, 1938 (USA) August 27, 1999 (USA re-release) |

the collapse of the old order of European civilization

war in the Bible

What is the Biblical perspective on war? Answer

extramarital affair, unfaithfulness, marriage

POW—prisoner of war, prisoner of war camp, jailer

prisons in the Bible

loneliness

starvation

generosity versus stinginess

courage, bravery, heroism, loyalty, self-sacrifice

pride versus humility

Why does God allow innocent people to suffer? Answer

What about the issue of suffering? Doesn’t this prove that there is no God and that we are on our own? Answer

ORIGIN OF BAD—How did bad things come about? Answer

Did God make the world the way it is now? What kind of world would you create? Answer

class differences

celebrating Christmas

insanity

mother-son and mother-daughter relationships / brother-sister and brother-brother relationship / brother-in-law brother-in-law relationship / grandfather grandson relationship

nobility

immigrant

Jews, Jewish slurs, anti Semitism

PATRIOTISM—Does being a Christian mean that I should be patriotic? Answer

reference to The French Revolution

Communist, Communism

feelings of futility of existence

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Jean Gabin … Le lieutenant Maréchal Dita Parlo … Elsa—Farm Woman Pierre Fresnay … Le captaine de Boeldieu Eric von Stroheim … Le captaine von Rauffenstein Carette … Cartier—l’acteur Peclet … Le serrurier Werner Florian … Le sergent Arthur Daste … L’instituteur Itkine … Le lieutenant Demolder Modot … L’ingénieur Dalio … Le lieutenant Rosenthal See all » |

| Director |

|

Jean Renoir |

| Producer |

| Réalisations d'Art Cinématographique |

| Distributor |

| World Pictures Corporation, The Criterion Collection |

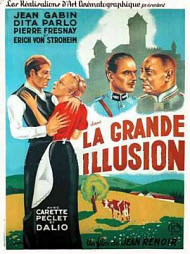

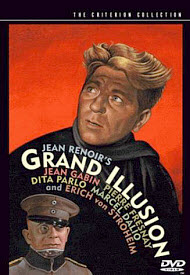

Jean Renoir’s “La Grande Illusion”, made in 1937, is arguably the best war film ever made. It tells the story of a group of French soldiers who are held captive in prisoner of war camps during the First World War. The film, itself, was taken prisoner during the Second World War when the Nazis invaded France and Josef Goebbel’s propaganda ministry seized the original negative. That original was missing for years, but it was not destroyed. It made its way to Russia and ultimately to Toulouse, France, where it was found and restored. The film has undergone yet another restoration and has now been released in 35mm after being digitally re-mastered. The release is a small one, available for viewing in only a few cities across the country, but it should be available on DVD sometime later this year.

The restoration is a sparkling gift to fans of the film, and to cinema history. The lush black and white photography, the sparse but stirring musical score, and the expertly choreographed performances sparkle with a new glow. “La Grande Illusion”, previously seen as a reconstructed version that Renoir put together from pieces of other copies of the film, is a work of art that explores the depth and complexity of the human heart in a way that is both personal and universal, yet for a film that aims for great themes, it handles its subject with considerable modesty and charm. Other war films have come close to matching its power and its beauty: David Lean’s “Bridge on the River Kwai”, Akira Kurosawa’s “Kagemusha”, Fred Zinneman’s “From Here to Eternity”, Stanley Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory”, and Michael Curtiz’ “Casablanca”, but none have surpassed it.

The film’s action takes place in two German prisoner of war camps and focuses on the lives of four French prisoners and one German commandant. What happens between the soldiers has as much to do with differences in social status and background, as it does with nationality. Renoir makes the point that men create all kinds of boundaries that separate them from each other, and that most of those divisions are foolish ones. War is man’s ultimate folly, for it brings him losses that are permanent, and victories that are pyrrhic and short lived. Renoir emphasizes this in a sequence in which news comes into the prison camp from the front (No battle scenes are depicted in the film.) about a hill in France that is taken by the Germans, then retaken by the French and ultimately won back by the Germans. Celebration and agony go hand in hand. A soldier puts the serial battles in perspective, when he mutters in despair about the once-honored hill: “Well, what is left of it now?”

There is very little violence in “La Grande Illusion”. In a movie about downed airplane pilots, there isn’t even a plane crash. One of the characters states, early in the film: “War should be waged with courtesy”. And in this film it is. Marechal (Jean Gabin), a former mechanic and now a French pilot is on a reconnaissance mission with fellow pilot and French aristocrat, Capitain de Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) when their plane is shot down by German pilot Captain von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). After capturing his French prisoners, Rauffenstein has them to lunch, a fancy spread in which pâté de foie gras is served on silver and china, before prison officials arrive to take the prisoners away. You can’t help but admire, and even like, Rauffenstein, even though he fights for the other side. He is a model of patriotism, military decorum and good manners. He is also a vain, stuffy, and over the hill snob. He knows that his time has come and gone, and he is not ashamed to say it, even as he struts about his crumbling fortress in a starched uniform, crisp white gloves, a shiny unused ceremonial sword attached to his waist, and a monocle. The affectation is taken to grand heights by Von Stroheim, who, aside from being a fine actor, is a bit of a peacock himself. Rauffenstein’s unvarnished self-awareness is as admirable as is his sense of duty and honor.

Many of Rauffenstein’s mannerisms are matched by the French aristocrat, de Boeldieu, who drapes his coat over his shoulders in a way that—I don’t know how else to say this—is so French, wears a monocle in the same pretentious way that Rauffenstein does, keeps his perfectly angled chin raised at all times and smokes with a delicacy that only a frequent patron at Maxim’s could master. Despite all that, he is as likable as his German counterpart. His charm and elegance outweigh his lofty airs.

All the performances are a joy to behold. Gabin and Fresnay were the great French, and European, stars of their time, and von Stroheim, an acclaimed silent film director in Germany and the U.S., was by then an icon in the movie world. The interplay is generous for a group of actors who were what we would today call megastars. They don’t abandon or hide that star presence (their aura is evident, even today), but they allow their characters, not their star personalities, to guide the action.

While in prison, the Frenchmen plan an escape. The men attempt to dig a tunnel from inside their barracks to outside the prison walls, but their plan is foiled when they are relocated to another prison. They attempt several more escapes at another prison before they wind up under Von Rauffenstein’s watch once again, this time in a thirteenth century castle that sits high on a cliff. The German commandant has wound up here after his own combat flying misadventure that has left him with multiple burns and a fractured neck, now held in place by a metal brace. He is determined to maintain the prison’s no escape record, but he is also determined to maintain the kinship with prisoner and fellow aristocrat, Boeldieu. The result of that relationship is both tragic and triumphant, but Renoir does not emphasize either aspect. There is no high or low point; nothing to cheer for or hiss at. His tone is gentle, and he lets the irony of the event speak for itself. Renoir reveals every aspect of his characters’ humanity; he lets us in on their deepest flaws, before he shows us the saving graces that redeem them. It is often in the men’s darkest moments that their true, and most honorable, qualities come to the surface. The haughty Boeldieu gives up what he always had the most pride in and clung to most passionately: himself. He lays down his life for his friends, even when those friends are below him in military rank and social standing. His act of charity is reciprocated by his enemy, Von Rauffenstein, who provides comfort, and a clergyman, to this fellow aristocrat during his final moments. Here we have one of the most intimate and touching death scenes in film history, acted out in whispers and quiet gestures. There are no cries of rage or tears of sympathy; only a meek request for understanding and forgiveness.

The redemptive power of charity as practiced by Bouldieu, and Rauffenstein inspires the bond between Marechal and fellow prisoner, Rosenthal (Marcel Dalio), as they escape and make their way to freedom. These two men are the commoners (although not an aristocrat, Rosenthal was a wealthy dressmaker before becoming a French officer) who may have been looked down upon by an aristocrat, but whose lives were saved by one. The two men harbor class resentments of their own, resentments that build and catch fire with the hunger, fatigue and growing despair of their daunting journey out of enemy territory. Marechal’s usual good nature turns ugly when he makes anti-Semitic remarks about Rosenthal, but his comments give way to repentance and to kindness. Jean Renoir is too keen an observer of human nature to divide the world into lovers and haters, heroes and villains, Semites and anti-Semites. In his world, as in the actual world, all men have human failings. It is in confronting and overcoming those failings, especially in moments of trial and darkness, that man discovers and reveals his humanity and his honor.

During their escape, Marechal and Rosenthal find shelter in the home of a German widow named Elsa (Dita Parlo). She lives alone with her daughter, Lottie. The war has taken everyone else from her. It is hard to imagine a more striking image of war’s toll than the one of the little girl sitting alone at a dining table that was meant to seat a large family. Elsa falls in love with Marechal; he falls for her, too, attracted as much to her sorrow as to her beauty, but he knows that he cannot heal her scars any more than the war or an eventual peace can mend the divisions between their countries.

“La Grande Illusion” is a grand mix of humanism, heroism, and adventure. It is also a good comedy of manners that contains quite a few funny scenes. The prisoners’ accounts of their calamitous escape attempts are not despairing; in fact, they are a hoot to listen to, especially Marechal’s aborted plan to sneak out of a camp disguised as a woman, only to be propositioned by one of the prison guards. It is also ironically amusing that the aristocratic officers speak to each other in English, when they do not want the lower class officers to understand what they are saying.

The film takes place during World War I, the war that was to end all wars. Perhaps that idea is what Renoir referred to in his title as a great illusion. Maybe he was referring to the belief that war is a noble pursuit. Whether it is or not, the film tells us that men can act nobly, even when they are a part of something that is not itself noble. The values of courage, brotherhood, and self-sacrifice may not overcome the ravages of war, but they help mankind to rise above the destruction, and they make heroism possible… As dark as the world can get, there is a light from another world that allows us to see, to believe, and to have faith in God and in each other.

I have seen “La Grande Illusion” many times over the years. With every viewing I see something new and sublime. I recommend it as an entertaining story, a great work of art, and an important part of history.

Violence: Mild / Profanity: Minor / Sex/Nudity: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.