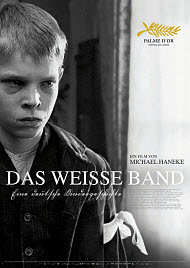

The White Ribbon

for some disturbing content involving violence and sexuality.

for some disturbing content involving violence and sexuality.

Reviewed by: Scott Brennan

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Better than Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Foreign Crime Mystery Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 24 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

December 30, 2009 DVD: June 29, 2010 |

Mercy in the Bible

SUICIDE—What does the Bible say? Answer

If a Christian commits suicide, will they go to Heaven? Answer

HYPOCRISY IN THE CHURCH — “I would never be a Christian; they’re a bunch of hypocrites.”

POVERTY—What does the Bible say about the poor? Answer

Poor in the Bible

REVENGE—Love replaces hatred—former israeli soldier and an ex-PLO fighter prove peace is possible-but only with Jesus

| Featuring |

|---|

| Christian Friedel (The School Teacher), Ernst Jacobi (voice of The School Teacher), Leonie Benesch (Eva), Ulrich Tukur (The Baron), Ursina Lardi (The Baronin), Fion Mutert (Sigi), Michael Kranz, Burghart Klaußner, Steffi Kühnert, Maria-Victoria Dragus, Leonard Proxauf, Levin Henning, Johanna Busse, Thibault Sérié, Josef Bierbichler, Gabriela Maria Schmeide, Janina Fautz, Enno Trebs, Theo Trebs, Rainer Bock, Susanne Lothar, See all » |

| Director |

|

Michael Haneke |

| Producer |

| X-Filme Creative Pool, Wega Film, Les Films du Losange, Lucky Red, Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, Mitteldeutsche Medienförderung, German Federal Film Board, Mini-Traité Franco-Canadien, Deutsche Filmförderfonds (DFFF), Austrian Film Institute, Vienna Film Financing Fund, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, Eurimages, Canal+, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, Michael Katz, Michael Katz, Margaret Ménégoz, Ulli Neumann, Andrea Occhipinti |

| Distributor |

| Sony Picture Classics |

“The White Ribbon” (German: “Das weiße Band”), written and directed by Austrian filmmaker, Michael Haneke, continues in his unique tradition of empowering the viewer at all costs, and creating a piece of cinema that is unforgettable. By empowering, I mean, he actively draws the viewers into the film whereby they are required to become both judge and jury without the help of gimmicks, script rewrites, or sloppy characters. Haneke’s use of locked down shots with characters entering the scene at the last possible moment and exiting nearly as quickly, shooting heavily condensed time sequences, and shots with a consistent camera focus on the opening and shutting of doors, have created a style that has essentially become its own genre. Although I had only seen a few of Haneke’s films prior to “The White Ribbon,” I believe I would now recognize one if I saw one (with the credits hidden)—much like I’m able to distinguish a Fellini or Bergman film—because of the inimitable techniques of the director.

Over the past 35 years Haneke has produced a large body of work—ranging from television, to stage, to movies. He has created award-winning films in French, German, and English—and continues to teach directing at the Film Academy in Vienna. It is this rich background, his devotion to the arts, and his apparent desire to communicate the story of the human condition—without judgment—that compels audiences everywhere to applaud his work. “The White Ribbon” received such applause this year, winning the prized Palme d’Or at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival and a 2010 Golden Globe Nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.

Despite the acclaim, this film is not for the faint at heart, since this one, like most of Haneke’s films, traffics in shock and awe. Not of the horror variety, but more Hitchcock-like: it’s what you can’t see on screen, but know is happening, that is so eerily troubling. It was even difficult to give it a moral rating (above) because, on one hand, there are many disturbing elements in the film that can affect the soul and trouble the mind. On the other, there is an enduring quest for truth that is ingeniously portrayed by the character of “the teacher” (Christian Friedel) and craftily written into the script. [I will address this quest for truth later—in my summary.]

This same teacher is doing the voice-over narration during the film (Ernst Jacobi)—and he’s recalling the series of unusual events that occurred in the year 1913-14, when he was still a young man, and hired on to work at the school near the estate of the Baron (Ulrich Tukur), in an ordinary German village. Why he’s doing this retrospective voice-over and for whom, we don’t know. But what he does say is that he was attempting “to clarify things that happened in our country,” leading even a casual observer to believe he might be on a personal contemplative investigation into the cruelty that was yet to appear inside Germany during the Great War (WWI) that was to follow. This is the backdrop and the setting, and for now, let it be clearly stated that this film most definitely earned its “R” rating, and is advisable only for adult viewing.

As a window into the past, the film is shown in black and white in its entirety, and in the beginning, with the sweeping wide shots of the estate and the flowing farm fields of wheat, the influences of Ingmar Bergman on Haneke become apparent. Even the shot rotations of the juxtaposition of the wealthy Baron’s family with the more modest steward’s family, and both of those in conjunction with the near poverty stricken ranch hands (to delineate social class and structure), are Bregmanesque. But the similarities in their style end there. Once the setting is painted on screen, the characters are introduced. As was stated before, the protagonist (the teacher) is re-telling the story, and he introduces the characters in an almost fairy-tale kind of way, naming them as they come on the screen, one by one: the baroness, the baron, the doctor, the steward, the children, the governess, etc., which gives the impression, as in Thornton Wilder’s play “Our Town”, this could be anyone’s village.

One of the central characters we are introduced to in the beginning is the Pastor (Burghart Klaussner), father of nine children, whose concerns for justice, morality, and decency in a strict Lutheran-like Protestant way seemed to permeate the village with a sense of foreboding—delineating the social mores and exposing the central themes that would be explored throughout the remainder of the film: guilt, transgression, responsibility, fear, forgiveness, denial, shame, and absolution. The white ribbon, itself a symbol of purity and innocence, is introduced early on as the mark of transgression for the Pastor’s two elder children—who in this case—were late for dinner, and would be forced to wear white ribbons for a time to remind them of how their disobedience was affecting the purity of their very souls. Of course, that would happen only after their spanking the next evening, in front of their siblings. So the white ribbon was exposed early on: like the “A” in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s, The Scarlet Letter, and the stage was set for the events to come.

The first event is at the onset when the doctor (Rainer Bock), returning from riding, is tripped on his horse by an invisible wire that is strung from tree to tree near his home. He exits the story for a season to convalesce his broken arm at a nearby hospital, and the village is left to solve the mystery, only they don’t succeed. In fact, when two inspectors come to investigate from the nearby town, there is little help from the village. The wire is missing, and, in fact, was never seen be anyone. Once again, in Haneke’s style—using a slow moving, non-descript entrance into the story—you are trapped. You don’t remember how you got through this portal in time—in what appeared to be at first a difficult, yet ordinary village—but now you feel as though you may be in an M. Night Shyamalan film without an escape. You have no place to go but forward in the story—hoping against hope that you won’t be held responsible for what you are about to see, because, somehow, instinctively, you realize you will be.

This event is followed by a series of others that show malice and aforethought on the part of someone in the village, including a burning barn, and another where a child is missing—and later found alive—but had been hurt, bruised, and humiliated. These are followed by even more sinister and troubling situations. But the questions remain, of course: who is responsible, and, even more important, why are they doing it? Those are just two of the questions that sink deep in the mind of the viewer, and that, of course, is by design.

By this time in the story, everyone is implicated to some degree, and no one appears willing to crack the code of silence. Slowly the narrator’s story begins to parallel what may have happened in his world and expanded beyond the village, perhaps to an entire nation. All hope for resolution is heaped upon the shoulders of the teacher, who is himself in love with a young girl named Eva, who rightly pursues his relationship with her without guile and with deliberate abstinence. Not wanting to spoil anything, it can be said that the story ends without a dénouement, expected for writer-director Haneke, but the questions linger behind: who is responsible and why did they do those things?

Objectionable Issues

Many of objectionable issues have been stated or implied throughout the background or story description above. The child spankings occur behind one of Haneke’s doors, and you only hear the sound. The first child that is kidnapped and hung upside down humiliated is found off screen, and is only reported by characters in the story. There are sexual situations that are inferred, including fornication by the doctor with his midwife and incest with his own daughter—the second one being the most disturbing scene in the film (in my opinion)—where her little brother walks in (the doctor and the daughter are both fully clothed) to investigate his sister’s muddled crying. There are a few slaps across the face between adults and spouses and several across the faces of children by parents. There is also a scene where a small bird is found with a scissors poked meticulously through its body, but it is sanitized without blood or guts—in character for Haneke—known to criticize most on screen violence as “wrapped up like chewing gum for consumption.”

Summary and Spiritual Significance

Undoubtedly, “the teacher” can be clearly seen as the protagonist in the film. He is the hope for the future, the pursuer of what is right and good, and for the right reasons. (His given name is Christian.) It is he who stands at the door of reason and inquiry, looking out daily from his schoolhouse and with his view of the world, fueled by sincere love, is willing to pursue truth—to the degree that it is possible—and is willing to teach it to others. Arguably, it pays off—since it is he who is telling the story so many years later, implying that he married Eva after all, had a family of his own, and had survived the terrors of WWI.

By the teacher’s actions in the film, it appears that he incorporates what the village Pastor is trying to live by [the words of Solomon] in the Old Testament in Eccl. 12:13, “Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man’s all,” and added to it, the words of Jesus from the New Testament in John 13:34, “A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; as I have loved you, that you also love one another.”

Only one other character in the story exhibits this kind of love consistently, and that is the Pastor’s youngest son (my favorite), who demonstrates it by a profound act—a “gift of love”—which is offered to his father in the film [sufficient evidence provided here to dismiss the critics with high-minded sophistry and of those who would love to make this film be about the evils of the church and religious systems]. I wanted to weep aloud, but I couldn’t, because I was not only taking notes, but fearful I might miss something in the following frames of film, if I became distracted. I waited until I got to my car to unleash what was pent up inside after watching this movie.

In his book, Film as Catharsis, Michael Haneke says the following:

“My films are intended as polemical statements against the American “barrel down” cinema and its dis-empowerment of the spectator. They are an appeal for a cinema of insistent questions instead of false (because too quick) answers, for clarifying distance in place of violating closeness, for provocation and dialogue instead of consumption and consensus.”

Michael Haneke’s intentions as stated above were achieved in my viewing of this film. I was empowered to make up my own mind about the unanswered questions, and now I wish to dialogue even more about this film—which might explain this rather lengthy review. I found this film to be disturbing yet remarkable, abhorrent—yet I can’t stop thinking about it. It has challenged me to personally resolve to live out my faith more by the “spirit of the law,” and less by the “letter of the law”—which brings forth death. If you are: an adult who is up for a challenge and one who views film as art to provoke and propel (not entertainment); are a film student; or a student in seminary; or studying apologetics; or want something to discuss in your adult home Bible study—then this film is for you and should not be missed. Otherwise, I suggest you pass it by.

Violence: Mild / Profanity: None / Sex/Nudity: Moderate

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

none

My Ratings: Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 4½