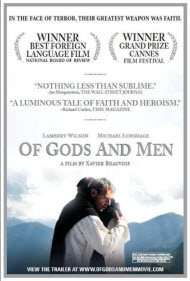

Of Gods and Men

for a momentary scene of startling wartime violence, some disturbing images and brief language.

for a momentary scene of startling wartime violence, some disturbing images and brief language.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Better than Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Foreign Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. |

| Year of Release: | 2010 |

| USA Release: |

September 3, 2010 (festival) February 25, 2011 (limited) DVD: July 5, 2011 |

FEAR, Anxiety and Worry… What does the Bible say? Answer

Why should Christians love Muslims? Answer

How can I pray for Muslims?

What does the Qur’an (Koran) say about Isa (Jesus Christ)? Answer

Do Christians worship three gods as Muslims claim? Answer

What does Islam teach about the crucifixion of Isa al Masih (Jesus) Answer?

Are most Muslims terrorists? Answer

As a Christian woman, how can I develop friendships with Muslim women? Answer

Read about the dreams & visions of Jesus occurring in the Muslim world today.

For more answers, see our overview of Islam for Christians…

Muslims are seeking the truth by the thousands. Visit IsaalMasih.Net and learn about Hazrat Isa, dreams and visions of the “Man in White,” the holy message of the Al-Kitab, and more…

Muslims are seeking the truth by the thousands. Visit IsaalMasih.Net and learn about Hazrat Isa, dreams and visions of the “Man in White,” the holy message of the Al-Kitab, and more…| Featuring |

|---|

| Lambert Wilson (Christian), Michael Lonsdale (Luc), Olivier Rabourdin (Christophe), Philippe Laudenbach (Célestin), See all » |

| Director |

|

Xavier Beauvois |

| Producer |

| Why Not Productions, Armada Films, France 3 Cinéma, France Télévision, Canal+, See all » |

| Distributor |

“In the face of terror, their greatest weapon was faith.”

I don’t often see a movie that has enough conviction and purity of heart to make me confront the superficiality of not just my movie-going experience, but of my life itself. The French film, “Of Gods and Men”, directed by Xavier Beauvois and written by Beauvois and Etienne Comar, is such a movie. It takes on what has become a touchy, often inflammatory, subject these days: the relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims in a politically charged atmosphere.

The setting is not Palestine or the Paris suburbs or lower Manhattan or an Ivy League campus. It is a small monastery in a small town in Algeria during that country’s civil war which took place during the 1990s. It is based on the true story of seven monks who were kidnapped from a monastery in Tibhirine, Algeria by Muslim extremists, and beheaded.

Although an Islamic group claimed responsibility for what seems to be a signature crime, questions have recently been raised about whether the Islamists were actually culpable or whether the Algerian army may have been involved. Some believe that the atrocity was an “inside job”, a charge that is applied to almost all terrorist attacks these days.

“Of Gods and Men” is an austere but gripping drama that keeps the war in the background as it focuses on everyday work and prayer in a way that initially seems tedious, but, over the course of the film, becomes engrossing and revelatory. It calmly depicts the way in which daily life’s small details are the stones that build the foundation for major accomplishments, and even for acts of heroism. The film’s drama and impact lies not in depicting how hard it is to do the right thing, but how hard it is to understand what the right thing to do actually is.

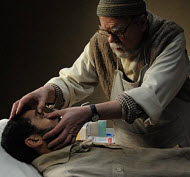

Uncovering the mystery behind the beheadings is not the goal of the film. Instead, Beavois lets the details of daily life in the monastery and the village unfold delicately as danger moves recklessly toward the church walls. Battles may rage outside the monastery grounds, but inside, the monks recite daily prayers, sing hymns, bottle preserves, wash dishes, plant crops and herd goats. The townspeople come daily to the monastery’s medical clinic to have their ailments treated by Brother Luc who, though elderly, frail, and asthmatic, devotes himself to the care of the villagers and toils against great odds (insufficient medicine and supplies, threatening terrorists) to heal, comfort and clothe his patients.

As the terrorist threat puts the monastery in increasing danger, the monks must decide to stay on or to leave. Would they foresake their vow and their mission if they leave? Are they prepared to accept the call to be martyrs if they stay? The film makes the point that martyrdom is not something that one seeks; it is what is left when all other options have been exhausted.

The film was shot in an abandoned monastery in Northern Morocco. The splendid cinematography by Caroline Champetier doesn’t just bring to mind the bucolic meadows of Robert Bresson’s “Balthazar” or the alluring cliffs of Michael Powell’s “The Black Narcissus”; it also recalls the classic landscape paintings of Millet and Corot, and even Rembrandt.

Speaking of Rembrandt, there is a great scene when the monks celebrate a meal together after they vote on how and where to spend their future—and before that future takes a tragic turn. Up to this point, the camera kept its subjects at a somewhat cool and analytical distance; in this scene, it zooms in and captures the faces of the men in close-up as they drink their wine and listen to Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake”. Their faces, elegiac and mournful, hopeful and resigned, determined and confused, have the same heart-gripping impact as do the Dutch master’s portraits. The scene is staged as a Last Supper, but not with the ironic Last Supper imagery of Robert Altman’s “Mash” or Luis Bunuel’s “Viridiana”. “Of Gods and Men” has a tenderness that makes these moments some of the most moving ever to be put on film.

The ensemble cast is sterling. Michael Lonsdale as the ailing but devoted Brother Luc and Oliver Rabourdin as the troubled, sometimes defiant Brother Cristophe are standouts, but Lambert Wilson (known to American audiences as the Merovingian in “The Matrix” movies) as Brother Christian, the monk’s leader, is a revelation. Christian lives his Christian faith in a way that embraces Islam, but still holds firmly to the truths of his own belief. Wilson portrays Christian’s moments of doubt, frustration, anger and determination with understated passion and with consummate empathy. It is an eloquent performance, one that reveals a good leader’s ability to feel for those he shepherds, but more importantly, that most honorable trait in any leader: the ability to listen.

There is a bit of foul language in the film, by a monk no less. There is more than a bit of violence, to be expected when the setting is a civil war. The beheadings are not shown on camera.

“Of Gods and Men” is a remarkable film that in these times when we hear so much about tolerance and outreach, gives us an understanding of what outreach really means. It’s more than an extended hand. Real outreach means giving oneself at the same time it means acknowledging, stating, and acting on what one knows to be true.

I saw “Of Gods and Men’ at the New York Film Festival on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. After the film there was a question-and-answer session between the filmmakers and the audience. There was a lot of talk about tolerance, Islamophobia, and religiosity (I still don’t know what that word means). Someone in the audience expressed concern that the film could be used by Ground Zero mosque opponents to further their cause to have the mosque construction site moved elsewhere. The director seemed intimidated by the question, although he answered it by referencing the U.S. President’s apology speech in Cairo and the need for more such outreach to bridge the divide between Muslims and the rest of the world.

On the Upper West Side such arguments, and battles, are fought in salons and at lecture podiums and on editorial pages. For the most part, no one has a stake in the real thing. The director needn’t have been phased by the audience response. Beauvois’ film makes a strong enough statement that values are rooted in respect for the truth and an understanding that agreements can be compromised but principles cannot. It is easy to take a stand from a distance, but it is not easy, as the film makes vividly clear, to stand for what is true and to be a witness to that truth.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Minor / Sex/Nudity: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

The movie’s pace is slow and subtle which is conducive to such contemplation. As a Catholic, the monk’s way of life and forms of prayer were familiar, but I can imagine how this might be foreign or even distracting to a non-Catholic. The monks were presented as being truly genuine in their seeking of, and practice of, God’s will.

Due to some violent scenes and weighty spiritual content I wouldn’t recommend this movie to a child younger than early/mid teens, but when you compare the “blood “n guts” content to the average movie that’s shown on television, it’s not that bad.

Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 3½

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 5

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Excellent! / Moviemaking quality: 5