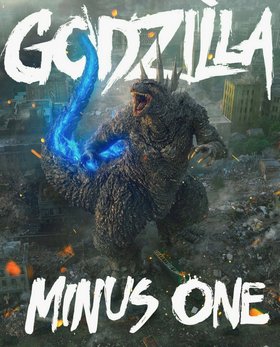

Godzilla Minus One

for creature violence and action.

for creature violence and action.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Average |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Young-Adults |

| Genre: | Sci-Fi Action Adventure Drama IMAX |

| Length: | 2 hr. 4 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2023 |

| USA Release: |

December 1, 2023 (wide release—2,308 theaters) Blu-ray: November 19, 2024 |

Near the end of World War II, a kamikaze pilot feigns technical issues with his plane and lands on Odo Island

Giant monster attacks—causing thousands of deaths

Survivor’s guilt after monster’s attack on a city

1940s post World War Two recovery in Japan

Godzilla is mutated and enlarged by the United States’ nuclear tests

A dishonored man adrift in a dishonored country

Facing one’s fears to act with courage on behalf of others

FEAR, Anxiety and Worry—What does the Bible say? Answer

Death of parents

Orphan girl / About ORPHANS in the Bible

DINOSAUR ORIGIN—Where did the dinosaurs come from? Answer

Are dinosaurs mentioned in the Bible?

WHY did God create dinosaurs? Answer

LIVING WITH DINOSAURS—What would it have been like to live with dinosaurs? Answer

EXTINCTION—Why did dinosaurs become extinct? Answer

EXTINCTION—Why did dinosaurs become extinct? Answer

NOAH’S ARK—Did Noah take dinosaurs on the Ark? Answer

Is there a connection between dragon legends and dinosaurs?

Visit our dinosaur-size Web site where you’ll discover a mountain of knowledge and amazing discoveries. How do dinosaurs fit into the Bible? You’ll find the answer to this and many more of your questions. Play games, browse and learn. Includes many helps for teachers and parents.

| Featuring |

|---|

|

Ryunosuke Kamiki … Koichi Shikishima Minami Hamabe … Noriko Oishibr> Sakura Ando … Sumiko Ota Kuranosuke Sasaki … Seiji Akitsu Hidetaka Yoshioka … Kenji Noda Yuki Yamada (Yûki Yamada) … Shiro Mizushima Munetaka Aoki … Sosaku Tachibana See all » |

| Director |

|

Takashi Yamazaki |

| Producer |

|

Gô Abe Shûji Abe See all » |

| Distributor |

| Toho International |

I was ten years old when I saw my first Godzilla movie. It was called “Godzilla, King of the Monsters,” and despite the clumsy editing, popsicle-stick set design and man-in-a-lizard suit party-store costuming, it remains a personal favorite. I have a fondness for the scaly and somewhat clumsy reptile who has been put through the ropes, or in his case, telephone wires, more often than Pauline Marvin or Wiley Coyote, and yet keeps coming back for more.

At age ten, I believed that Godzilla, and all the other screen monsters, were real. Even today, when I hear a particularly loud siren, not an uncommon sound in the town where I live, that ten year old boy whispers in my ear: “Uh oh, run for it; that alarm means Godzilla is entering the harbor!”

With each new Godzilla rendering, I make it a point to see the movie even when I know what to expect: enormous reptilian teeth, exhaled gusts of fire, crumbling buildings, crowds of people running, and the a bevy of scientists in lab coats scratching their heads in wide-eyed wonder and brow-furrowing confusion. The script never changes; it’s always a recycling job, and instead of shiny new plastic we wind up with another crumbly piece of cardboard.

“Godzilla Minus One,” written and directed with intensity and commitment by Takashi Yamazaki, may not be the masterpiece that many critics are calling it, but it is nonetheless a marvel. It is a true original that pays enough respect to the monster movie genre to place it in the ranks of classics such as “The Cabinet of Dr. Caliguri,” “Bride of Frankenstein,” “Cat People,” and “Aliens.”

Yet the new Godzilla film is much more than a monster movie. It has the humanity and the pathos of the great war movies, and all great movies, of the past. It respects the traditions of family life and patriotism in ways that we have not seen on screen in a long time. It reminds me of the sadness, but also the strength, of Jean Renoir’s soldiers in “Grande Illusion,” and William Wyler’s veterans in “The Best Years of Our Lives.” It lays bare the evil of war and its tragic effects on humanity, but it pays tribute to codes of obedience and honor, ones that are written on the human heart (Romans 2:15).

Kiochi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) is a kamikaze pilot who in the waning days of World War II is sent on what will be his last mission. He neglects his duty and does not complete his assigned task. Instead, he diverts his plane and lands on an island inhabited by repair men who fix damaged aircraft. They find nothing wrong with Kiochi’s plane and are suspicious of him.

At night, after the sun goes down, Godzilla, large but not mammoth in size, appears on the island and goes about doing what Godzilla does: crushing the buildings on the island while chewing up and spitting out every human in site. Those left uneaten beg Kiochi to get in his plane and fire his artillery guns at the monster in order to kill it. Kiochi boards the aircraft, but freezes in fear as Godzilla continues his rampage. Most of the repairmen are now dead. Kiochi has forsaken the Japanese code of honor not once, but twice. He is now a dishonored man adrift in a dishonored country.

“For evils have encompassed me beyond number; my iniquities have overtaken me, and I cannot see; they are more than the hairs on my head, my heart fails me.” —Psalm 40:11-12

After the war, Kiochi returns to his home town to discover it has been destroyed in an air raid—one that has left both of his parents dead. In the midst of the destruction he bumps into Noriko (Minami Hamabe), a young woman who is also alone except for an orphaned baby she has found in the rubble. He reluctantly takes both Noriko and the child into his bombed out house where they forge a platonic relationship, one that restores the home and provides shelter and sustenance for the baby girl.

The drama of people attempting to rebuild their lives plays out against the backdrop of a country trying to rebuild itself after losing a war and suffering the fallout from the nuclear explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Both citizen and state must come to terms with what they have become during the war and what they will make of themselves in its aftermath. Kiochi is consumed by remorse and guilt, as is his homeland, but he and his countrymen understand that in order to build something out of the rubble they must unite and forge ahead.

Yamazaki does not shy away from examining how cultural tradition and codes of honor can be twisted in ways that lead to imperial aggression and kamikaze warfare, but he emphasizes the basic values of family, friendship and country, making those the backbone of his story. The woman keeps the home and nurtures the children; the man, with the encouragement, and sometimes the slap, of a woman, does the work he is meant to do: flying a plane, fighting the enemy, and protecting the home that the woman has made.

Eventually Godzilla makes another appearance when Kiochi takes a job on a schooner that searches out and destroys mines left behind by allied ships in the sea. The plot device that has the monster turning up wherever the story’s hero happens to be is a stretch, but it plays well to the theme of Godzilla representing all that has befallen Japan, which Kiochi represents in microcosm. The monster symbolizes Japan’s sin, a mark on the country’s soul, one from which its people cannot escape.

By the time Godzilla reaches Tokyo, he is much bigger, much more destructive (he’s now radioactive, spitting blue fire and sporting neon blue scales), and acting out major anger issues. The bigger and badder version compounds Kiochi’s sense of guilt for failing to confront the evil when it first appeared in a somewhat containable form on the repair shop island.

In the big city, we get back to the clichés of people being trampled in the streets, trains derailing and dangling from precipitous heights, and scientists devising attack plans with graphs and pointers. It’s mostly boilerplate filler, but better boilerplate than most other monster-on-the-rampage movies. The scientists and the attack forces have discussions and debates that are actually interesting, even engrossing. And I got a real kick out of the scene in which Godzilla wipes a crew of newsmen off the roof of a building. Characteristically unaware of true danger, the press seeks what is sensational while ignoring what is real. Such haughty spirits set themselves up for quite a fall (Proverbs 16).

“Godzilla Minus One” succeeds admirably because it is a human adventure that happens to have a monster as its antagonist. It conveys a real sense of what is good in humanity and what is not good, and has a purity of vision that is missing in most contemporary movies. I’ve seen that sharp but tender insight in the work of now deceased Japanese directors: all the Kurosawa films or Teshigahara’s “Woman in the Dunes” or especially Yasujiro’s “Tokyo Story,” also set in the aftermath of World War II. I rarely see such naked humanity on the screen aside from some of the films of the post World War II Italian Neo-Realist period: “Open City,” “The Bicycle Thief,” and “Rocco and His Brothers.”

Where films such as “Killers of the Flower Moon” and “Oppenheimer” tinker, waver, and hang their heads, “Godzilla Minus One” stands forthright and strong. And it is entertaining on a grand scale despite its modest budget. This is a remarkable film, one that respects its audience and does not turn away from its country’s soul or from its own.

It longs for that soul. And says yes to its calling.

“He lifted me out of the slimy pit, out of the mud and mire. He set my feet on a rock and gave me a firm place to stand.” —Psalm 40:2

- Violence: Heavy

- Profane language: Minor

- Vulgar/Crude language: Minor

- Drugs/Alcohol: Minor

- Nudity: None

- Sex: None

- Occult: None

- Wokeism: None

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

This film is a game changer to the point where you don’t mind it so much when the Big Guy isn’t in frame—unlike many, many other G-movies. The human element is understandable, sympathetic, and is begging for redemption.

The ending may not be a huge surprise, but the overall story, CG quality, and emotional impact is an amazing experience for any long-term G-fan (and other normies). 5 Tail Swings out of 5!

Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 4

Moral rating: Good / Moviemaking quality: 5

While the other movies from the Monsterverse have been significantly more fun and less offensive than KOTM, none have them (except maybe 2014) have really stood out to me as having all that much artistic value.

“Godzilla Minus One” on the other hand, is a prime example of why Japan does Godzilla so much better than America. Minus One brings Godzilla back to his roots as a destructive result of the atomic bomb, and uses him as a representation of Japan’s post-war trauma. The movie’s themes of guilt, redemption, sacrifice, and hope are unique among many modern monster movies, and elevated by the movie’s incredible human characters.

This is the best kaiju movie since the Heisei Gamera Trilogy, and the best Godzilla movie since the original. Easily the best movie of 2023, a masterpiece that everyone, kaiju fan or not, should see. I cannot recommend this movie more. Go watch it.

Moral rating: Better than Average / Moviemaking quality: 5

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.

My Ratings: Moral rating: Average / Moviemaking quality: 5