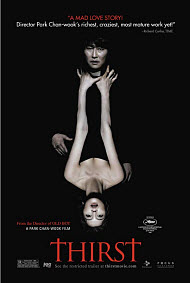

Thirst

for graphic bloody violence, disturbing images, strong sexual content, nudity and language.

for graphic bloody violence, disturbing images, strong sexual content, nudity and language.

Reviewed by: Jim O'Neill

CONTRIBUTOR

| Moral Rating: | Very Offensive |

| Moviemaking Quality: |

|

| Primary Audience: | Adults |

| Genre: | Foreign Horror Drama |

| Length: | 2 hr. 13 min. |

| Year of Release: | 2009 |

| USA Release: |

July 31, 2009 DVD: November 17, 2009 |

Blood in the Bible

What are the consequences of sexual immorality? Answer

VIOLENCE—How does viewing violence in movies affect families? Answer

NUDITY—Why are humans supposed to wear clothes? Answer

Satan in the Bible

Is Satan a real person that influences our world today? Is he affecting you? Answer

| Featuring |

|---|

| Kang-ho Song (as Priest Sang-hyeon), Ok-vin Kim (Tae-joo), Hae-sook Kim (Lady Ra), Ha-kyun Shin (Kang-woo), In-hwan Park, Dal-su Oh, Young-chang Song, Mercedes Cabral, Eriq Ebouaney, Hee-jin Choi, Woo-seul-hye Hwang, Hwa-ryong Lee, Mi-ran Ra |

| Director |

|

Chan-wook Park “Oldboy,” “Lady Vengeance,” “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” |

| Producer |

| CJ Entertainment, Focus Features, Moho Films, Universal Pictures, Chan-wook Park, Ahn Soo-Hyun |

| Distributor |

“Winner of the Grand Jury Prize in the 2009 Cannes Film Festival”

I tend to avoid movies that target a teenage audience. Sometimes that’s my loss; other times, not. I was visiting a friend last night. We were too tired to go out to the movies, so we put in a DVD of “Twilight,” the first in what’s called “The Twilight Saga,” and started to watch the film.

I was curious to see what the draw was, what is making these vampire updates such runaway hits. We turned off the DVD player after one hour. Up to that point, the movie was going nowhere. The first hour was all exposition, and the last thing a vampire movie needs is exposition. The wan acting, the lazy direction, the cold cinematography, and even the drag-like make-up made this sanguine-obsessed tale bloodless. It was as thin and pale as its robotic male lead.

The night before, I had watched another vampire film called “Thirst,” made by Korean director, Park Chan-wook. “Thirst” sticks to the essentials of the vampire genre, but it eschews the romantic melodrama of “Twilight.” Park’s movie is graphic, and at times obscene (the blood-letting and the blood-taking are gruesome), but Park uses the supernatural, not as a fanciful charm, but as one force among many against which man must struggle to find redemption.

Man’s own ego, or his desire to “be like gods who know what is good and what is bad” (Genesis chapter 3) is as much his enemy as is the force that turns him into a vampire.

Those of us who have watched vampire movies over the years know that the vampire’s game is always the same. The vampire’s core is evil, and Evil doesn’t change much. Its lack of imagination is evident in the way it repeats the same sins over and over again. All we need do is read history books to see the evidence of this.

Man, on the other hand, does have an imagination. We have not seen heaven, but we often imagine it, and we long for it. The evil one has seen heaven, has known heaven, and has rejected it. Our human longings are about heaven, even when those longings are misguided and they take us in the wrong direction. They are misguided when we allow the evil one to take the reigns, and we believe in the false promises of a heaven on Earth. The vampire represents the acceptance of that bargain: he can turn stones into bread, he can fly, and he has power over his dominion.

The cost for that power is the soul, the very self, which leaves a hungry void that cannot be sated no matter how much food, blood and power the vampire consumes. One of the best film openings I’ve seen was in “Andy Warhol’s Dracula” made in the 1970s by Paul Morrissey. Count Dracula reigns as a vampiric prince, but has gone beyond being a shell of a man to being invisible. He sits at his dressing table, and applies make-up, a blonde wig, and fine clothes until he becomes an illusion, a stunning vision of a man, but underneath the finery there is an emptiness as cold as the Count’s eyes. The vampire’s power comes from taking something human and corrupting it. But the prince of darkness is a gentleman, and he always asks before taking. Stephen King’s vampires in “Salem’s Lot” would not come through the window or door unless a human opened the portal for them. Eve was not fed the “apple;” she consented to a request to eat it.

Bram Stoker published Dracula in 1897. Dracula is not a great novel, but it’s a masterful work, nonetheless. I still consider it the scariest book I have ever read. Stoker’s book came out not too many years after Charles Darwin had published The Origin of the Species and presented his theories of natural selection and survival of the fittest. The actual science of genetics was established about the same time by the Austrian monk, Gregor Mendel, but Mendel’s findings would not gain wide acceptance until the early part of the 20th Century. Darwin’s belief that living things became stronger by the development of traits that were passed along by blood was a theory that must have influenced Stoker. He lived in Victorian England, but he hung with a theatrical crowd (he managed London’s Lyceum Theater and was a personal secretary to actor Henry Irving), so he must have been conflicted about Darwin’s theories, as well as the changing mores of the times. Would Darwin’s findings bring us a better life or would they create a monster? It’s possible that Stoker’s musings on the subject created one of the great horror staples of literature and film, one that translates, as most great myths do, to other languages and cultures quite well.

“Thirst” is a fine example of this. The Korean film may use a lot of the cliches we’ve seen before, but Park makes them look new. And he alarms and frightens in ways that I haven’t seen since the early days of F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” or Tod Browning’s “Dracula.”

The story

Father Sang-hun (Song Kang-ho) is a Catholic priest who views his ministry as a heroic mission; he wants to save lives even if it means risking his own, but beneath his desire to save his fellowman there seems to be a core of shame and guilt that he is desperate to atone for. His priesthood is not so much a calling as it is a quixotic quest. He chooses his mission when a deadly virus, ironically called the Emmanuel virus, starts to infect his community. Father Sang-hun volunteers for a secret vaccine development trial in which he is injected with the virus in order to test the vaccine. The vaccine fails, and he is overtaken by the deadly virus. He is treated with a blood transfusion which eradicates the virus, but transforms him into a vampire. His rapid recovery and his newfound strength bring him the heroic reputation he seemed to long for. His parishioners believe he has special powers and flock to him to be healed. However, his own cure is only temporary, and he succumbs again to his disease while playing mahjong at his childhood friend’s home.

When he comes back to life, yet again, he has even greater strength, as well as some new, or newly awakened, desires. In order to sustain his “life,” he steals blood from the hospital blood bank, and sucks blood from the intravenous tubing of a comatose hospital patient. His crimes begin with these acts, and so do his rationalizations. He tells himself that by stealing the blood he is actually being charitable, even to the patient he is taking it from. Each subsequent offense that he commits is accompanied by a similar explanation, as his sins grow in number and gravity.

The priest falls for his friend’s young wife, Tae-ju (Kim Ok-vin). He begins an affair with her that leads to the murder of her husband, and to a series of other murders in order to cover up the first murder.

The priest continues to rationalize, but his reasoning becomes weaker and more transparent with each successive crime. He transforms Tae-ju into a vampire, not to save her life, but to fulfill his own needs. After her transformation, he discovers that his lover’s bloodlust is boundless, while his is still tempered by the guilt and shame that plagued him when he was human. His semi-existence becomes a barren one; even the evil deeds become mundane and routine. There is a particularly gruesome scene, among many gory moments, in which the lovers suspend their dead victims over a bath tub and let the blood drain from the amputated feet in order to collect the serum they need to live another day. “Let gravity do the work,” he laconically tells his lover. Father’s excuses run out when he continues his crimes and takes a child as a victim. He is then exposed for what he is—to himself and to the people who once held him up as a savior.

Metaphor

Vampirism is a metaphor for damnation. The vampire’s long life and power come at a price. A vampire tale, book or movie, can only have an impact if it gives a sense of how high that price is. The story better have a soul, if it’s a story about selling one. I couldn’t find a core in the first “Twilight” movie, but I did see one in “Thirst.” Ultimately it’s his humanity that in the end brings Father Sang-hyun some degree of salvation from the super-humanity that made him less than human. Evil appeared boundless in his newfound world, as it does in our everyday world, but when evil took its biggest chance, grace touched what was left of a human soul and redeemed it. Park’s use of a pair of worn shoes as a symbol of this grace warms an otherwise barren ending, another way that the director takes a genre staple and gives something both familiar and altogether new.

The performances in “Thirst” are all near-perfect. I especially liked Kim Hae-sook who plays Tae-ju’s mother in law, Ok-bin Kim. Mrs. Kim suffers a stroke and becomes paralyzed. She realizes that her daughter in law and Father Sang have murdered her son, but she is unable to move or to speak, and thus expose them. The murderous couple plot and kill and lie, but are less and less able to see reality, while the paralyzed woman cannot move but sees all. Ultimately, her truth triumphs over their lies and is a witness to the destruction wrought by those lies.

On the surface, “Thirst” is a gorefest; there is abundant, and sometimes unwatchable violence and bloodletting. There is also graphic sexuality, and some nudity. However, the vampires in Park’s film have no allure. Song is not Lugosi or Lee or Langella or Cruise. His ordinariness makes him more accessible, more understandable and more tragic. Psalm 26 sings of a man who loved being in God’s house where honor dwells.

“Do not take away my soul along with sinners, my life with blood-thirsty men, in whose hands are wicked schemes, whose right hands are full of bribes…”

With so many bribes being offered to us in this life, it’s easy to overlook a true gift: life itself. The supernatural, and in many ways unnatural, “Thirst” makes that natural point poignant and clear.

Violence: Heavy / Profanity: Heavy / Sex/Nudity: Heavy

See list of Relevant Issues—questions-and-answers.

PLEASE share your observations and insights to be posted here.